Sunrise History:

Sunrise History:This is the first part of a series documenting the fifty-year history of Sunrise Inc.—the studio that produced the Mobile Suit Gundam series—and introducing some of the people who contributed to it.

Officially dissolved in 2022, when it was incorporated into Bandai Namco Filmworks Inc., Sunrise was originally established in 1972 as a pair of companies named Soeisha Inc. and Sunrise Studio Ltd. In this installment, I'll cover this first incarnation of the company and briefly discuss the development of its major works.

The Sunrise saga will continue in Nippon Sunrise 1976~1987!

The company that would eventually become Sunrise Inc. was founded by seven former employees of Osamu Tezuka's pioneering animation studio Mushi Production. By 1972, Mushi Pro was clearly in trouble—for reasons explored in detail in Matteo Watz's History of Mushi Pro—and many of its staff were leaving to start their own companies or pursue freelance careers. In an extensive interview in 2002's "Gundam-Mono: The Men Who Made Gundam," longtime Sunrise employee Masao Iizuka describes the situation as follows:

Masao Iizuka — Gundam-Mono: The Men Who Made Gundam

Mushi Pro expanded until it was producing five works at the same time, and had more than four hundred employees. Its headcount had now reached a point where it could be called a major company, not just a midsize one. Ultimately, though, its organizational capability and financial strength remained just as weak as when it was originally founded. It was in a situation where it was constantly receiving advance payments for its next works and using the money to fund the production and broadcast of the current ones.

In the course of this animation history, Mushi Pro's condition gradually worsened. Now there were so many works competing with each other, its supplemental income from character merchandising fell, and on the content front there was the problem that not all of Tezuka-sensei's works could be turned into TV anime. With all these various problems piling up, by the beginning of the seventies the company's bankruptcy was inevitable.

—And then Sunrise was one of the companies that was created as Mushi Pro was heading for bankruptcy.

By that point, Toei Doga, Mushi Pro, and Tatsunoko Production had all become large organizations. But working conditions were poor everywhere. That's why they formed labor unions, and why the labor movement was so vigorous from the mid-fifties to the end of the sixties. In that kind of situation, the work would fall behind due to labor disputes. A lot of animators are the kind of people who just want to draw pictures and get on with their work, so one after another, they started going independent and establishing subcontracting companies.

This development made it possible to establish a business like Sunrise, which didn't have an actual production work department, but was able to plan, produce, and sell animation while subcontracting the production work itself. That was pioneered by Tokyo Movie Shinsha. Before that, the company itself had to take on all the staff required to make things.

In contrast to Madhouse, a studio formed around the same time by former Mushi Pro animators, the Sunrise founders were middle management staff whose expertise lay mainly in planning, sales, and production management.

Ryosuke Takahashi — Sunrise World Creator Interview 15

Madhouse was formed at roughly the same time as Sunrise, and it was another company created by people who'd left Mushi Pro, but it was somewhat different from Sunrise. In a normal company, the people who started Sunrise would be equivalent to department heads. They knew exactly what had brought down Mushi Pro, but they were in a position where they didn't have to take the blame for it.

Indeed, it's noteworthy that among the seven founders of this upstart animation company, only one had any expertise in the physical work of making animation.

Masami Iwasaki & Ryosuke Takahashi — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 5

Takahashi: The company was started by seven people. Why these particular members? I never had the impression the seven of you were especially close when you were all at Mushi Pro.

Iwasaki: Ito-chan, Mr. Yamaura, and myself were all in the same group at Mushi Pro. Towards the end, it was organized into a divisional structure. It was made up of groups that each handled their own sales, planning, and production, with a whole staff that included two series directors, dozens of animators and animation directors, dozens of finishers, and even background and photography staff. Mr. Yamaura was in planning, Ito-chan was in sales, and I was in production, so that was more or less set in stone. And then Kicchan—Mr. Kishimoto—was in a different production department... with Shibuyan.

Takahashi: So that's how it was.

Iwasaki: As for Mr. Numoto, it was his job to cultivate animators in general.

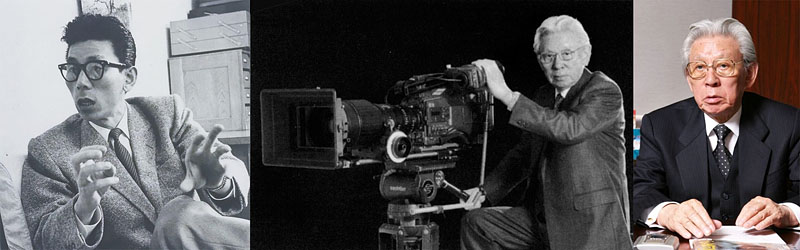

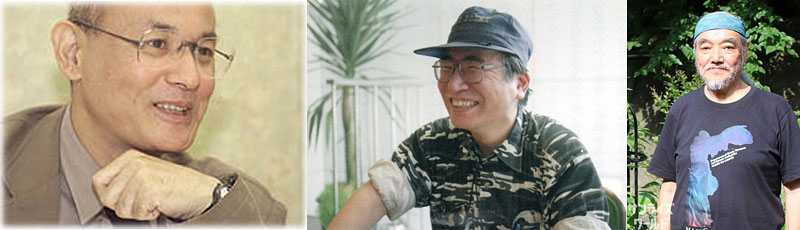

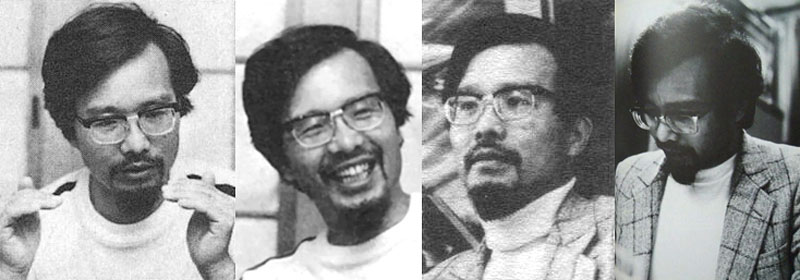

Archival photos of Tohokushinsha founder Banjiro Uemura, taken between 1962 and his death in 2019. The first and second are from the Speedy Gallery website, and the third is from Shogakukan's News-PostSeven site.

Low on startup funds, Sunrise's founders approached Banjiro Uemura, president of the dubbing studio and film distributor Tohokushinsha. In return for its capital investment, the new business they created would operate as a Tohokushinsha subsidiary. The setup consisted of two separate companies, with Soeisha Inc. handling planning, sales, and production management, while Sunrise Studio Ltd., located in Tokyo's Kami-Igusa neighborhood, would be doing the actual animation production work.

Eiji Yamaura — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 2

We were utterly broke and didn't have any money. Then fortunately, Tohokushinsha provided half the startup capital, and the seven of us scraped together the remainder, which was about 100,000 yen apiece... You'd have to ask Mr. Ito for the exact figures. Thus we took our first faltering steps. People talk about having dreams, and it's not like we didn't have any, but when you're dealing with the real world things aren't so easy. To be frank, all you're thinking about is how to survive.

Masami Iwasaki — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 5

Though we weren't getting paid at Mushi Pro, we all scraped together the capital to create a company. We didn't have any money (laughs) so gathering 100,000 yen apiece was really tough. My wife had to spend all the money she'd brought for our wedding on living expenses, so it was pretty scary. (laughs)

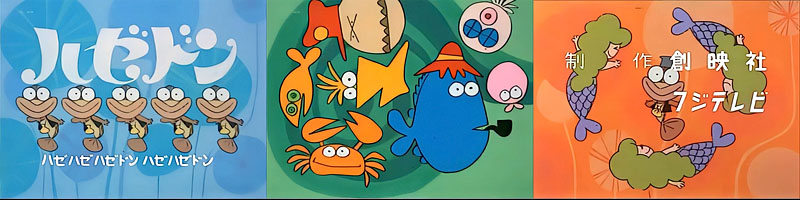

Soeisha and Sunrise Studio were formally established in September 1972, just one month before their debut series Hazedon began airing on Fuji TV. But before discussing this work, we should first introduce the company's seven founders.

Drawing heavily on Ryosuke Takahashi's "Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream" interview series, here are brief descriptions of the seven Mushi Pro refugees who created the company that later became Sunrise. Not all of them would go on to play major roles in the company's history—two departed in the mid-1970s, before Soeisha became Sunrise—but three would go on to serve as Sunrise presidents, and one of the first to leave would reappear to play a major role at pivotal moments.

Yoshinori Kishimoto, who became the first president and CEO when Soeisha and Sunrise Studio merged to form Nippon Sunrise Inc., served as a producer or production manager on many of the company's early works. In this role, he was responsible for setting up the original Sunrise Studio production site and physically supervising the creation of its debut series Hazedon. He also produced the company's second series, 0-Tester, and took over as producer on the second half of Reideen the Brave.

Ryosuke Takahashi & Katsumi Bando — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 2

Takahashi: Mr. Kishimoto and Mr. Iwasaki were both production people. But their natural strengths...

Bando: Their natural strengths were different.

Takahashi: Kicchan was originally a film kid. He was always talking about Wilder and Wyler and Hitchcock. And, as far as Japan, Shohei Imamura.

Bando: Although Kishimoto was in production, I'd say he was truly a producer, or at least he made things. He didn't know much about the production site and he didn't care about details. In short, he really wasn't interested in the kind of production site where you're worrying about things like how to color each part.

Takahashi: But by the last moment in the schedule, he was actually painting a lot of the colors.

Bando: (laughs) There was no other choice. Iwa-chan had already seen to that.

Kishimoto died suddenly on October 2, 1981, just as the slowly building success of Mobile Suit Gundam had assured the company's long-term future. In his "Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream" interview series, Ryosuke Takahashi recalls Kishimoto with deep affection.

Ryosuke Takahashi — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 2

As my senior when I was a production assistant at Mushi Pro, he's someone to whom I was much indebted. He was a hearty man with a big build who loved his favorite drinks. But he also had a childish side, as he loved building plastic models, filling his office with all the aircraft and ship kits he'd built and saying he'd build them some day when he had free time from work. He fell sick and died just as the success of Gundam had been confirmed... what a pity. He was only 42 years old.

Masanori Ito succeeded Kishimoto as Sunrise's second president. Based on Takahashi's description, Ito's skills lay very much on the business side, and he doesn't seem to have played a significant role in the creation of the animated works themselves.

Ryosuke Takahashi — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 2

When the company was founded, he was stationed at Tohokushinsha as Soeisha's representative. Plump and fair-skinned, with a close-shaved head and wearing a suit, he looked a bit like a yakuza lawyer. He used to show up unexpectedly at the Kami-Igusa studio and flop down on the only sofa that had springs in it, lounging there like a sea lion and barking at the girl from the production desk to bring him tea. The young staff who were staying up every night at the production site thought he was arrogant and insensitive. It's no wonder, since that worn-out sofa was the only thing they all had for a bed...

But appearances can be deceiving. That arrogant man was a surprisingly meticulous manager, and Sunrise's current position is largely due to his strategies. And what's more, he's actually very kind. He's a classic example of how you can't judge a book by its cover.

Left: Eiji Yamaura in 1980 and 1991.

Right: Yamaura in 2002, when he was interviewed for the "Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream" series.

Eiji Yamaura, who followed Ito as the company's third president in 1987, was previously in charge of planning—that is, developing ideas for new works and working with potential sponsors to get them approved. This meant that Yamaura was central to the creation of most of Soeisha's and Sunrise's original works during the company's first 15 years. The pen name "Hajime Yatate" that appears in the credits of so many Sunrise creations, officially representing the collective work of the Sunrise planning office, is largely an alias for its charismatic chief.

Yoshie Kawahara — Great Mechanics G, 2022 Winter

The name Hajime Yatate represents everyone involved in drafting the plan, particularly the first head of the planning department, the late Mr. Eiji Yamaura (the third president of the company). Then, after Mr. Yamaura moved over to the management side, the central planning role passed to Koichi Inoue, who may be familiar to the readers, and he became "Hajime Yatate II." (Since Inoue later became my husband, I've omitted the honorific.)

I heard from my direct superior Mr. Masao Iizuka, the planning office desk chief (at the time), that the name Hajime Yatate means you're about to set out on a difficult journey. It comes from the line "Yatate no hajime" from the poet Matsuo Bashō's "Oku no Hosomichi," and incorporates the meaning "We did this for the first time!"

Yoshie Kawahara — Great Mechanics G, 2023 Spring

To me, Mr. Yamaura was a big man who was always frantically running around, laughing loudly and heartily, an impatient and careless boss full of anecdotes that made me burst out laughing every time I heard them. When it came to planning, though, he'd set you challenges that made you think "That's ridiculous!" But from the 1970s to the first half of the 1980s, most of the works that probably come to the reader's mind when you hear the name "Sunrise" existed only because of Mr. Yamaura.

As I've frequently mentioned, in a nutshell, "planning" is what's required to achieve consensus and cooperation with the sponsors, advertising agency, TV station, and so forth when an anime work is being created for TV broadcast. In other words, it means thinking about the work with the question "Will each of them make money by broadcasting this anime on TV?" constantly in your mind.

However lofty the narrative, or however elaborate the work's designs, images, and animation, Mr. Yamaura would say "If your partners don't make money, it won't lead to your next job." That's what creating commercial anime is all about. In the works created with this conviction, when they write "Planning: Hajime Yatate," it wouldn't be wrong to say "Planning: Eiji Yamamura." In fact, if you ask the veterans who were involved in planning with Mr. Yamaura back then, they'll all say "That was Mr. Yamaura's plan."

Left: Masami Iwasaki in 1983.

Right: Iwasaki in 2002, when he was interviewed for the "Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream" series.

Masami Iwasaki, one of Sunrise's main producers, was known for his skillful management of budgets and schedules, the latter of which he tracked using color-coded scrolls. In the "Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream" interview series, Hazedon art director Katsumi Bando recalls that Iwasaki hadn't yet joined Soeisha when its first series was produced, since he was still concluding business at Mushi Pro. His first Soeisha producer credit was on Star of La Seine, and after serving as production manager on Com-Battler V, Voltes V, and Daimos, Iwasaki went on to produce The Unchallengeable Trider G7, Robot King Daioja, and Fang of the Sun Dougram.

Masao Iizuka & Ryosuke Takahashi — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 6

Takahashi: Mr. Iwasaki created not only the production site, but also the model for the company's general affairs, or rather its general administration. He worked really hard... Without a practical businessman like that, they'd just have been a bunch of talkers. Merely cheerleading isn't good enough.

Iizuka: He was the factory chief. A great factory chief who could manage schedules and money.

Katsumi Bando — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 8

Once Iwacchan came along, Sunrise started to become more robust.

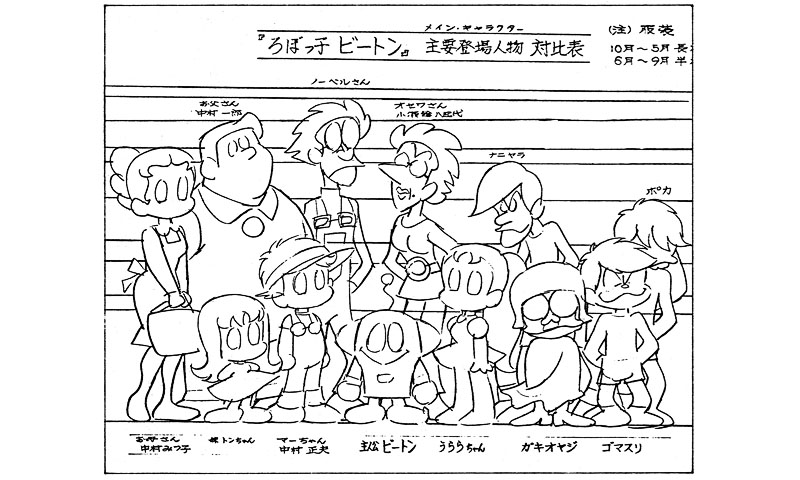

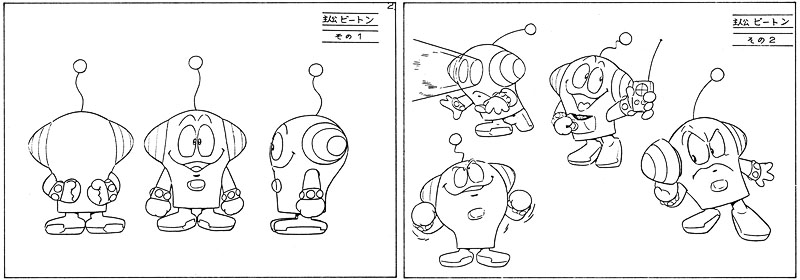

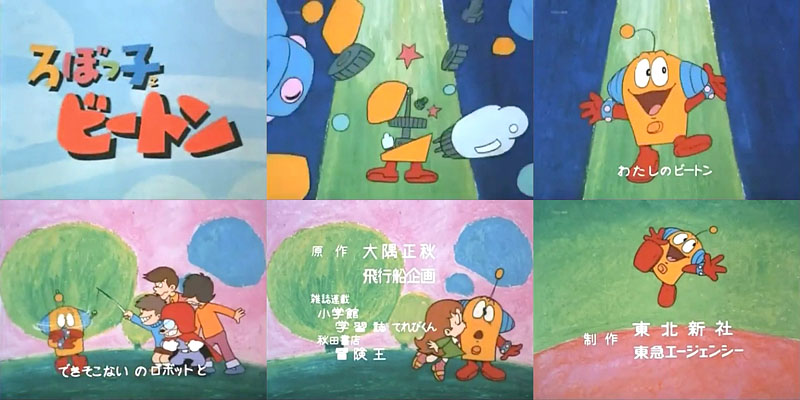

Yasuo Shibue was the other main producer among the founding members. After producing the first half of Reideen the Brave and Robokko Beeton, he went on to produce The Unchallengeable Daitarn 3, the original Mobile Suit Gundam, and the 1982 TV special White Fang Monogatari. Shibue left Sunrise—and the anime industry—at some point in the early 1980s, soon after Kishimoto's passing.

Ryosuke Takahashi — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 6

Though he wasn't that tall, he was a hardboiled tough guy who looked really perfect in a trenchcoat. He had tremendous authority over sloppy animators, and I hear that merely mentioning his name made it easy for production assistants to collect work from animators. His fondness for "cult shows," as mentioned by Mr. Iizuka, is in part confirmed by the fact he was the original producer of Mobile Suit Gundam. After leaving Sunrise, he cut all his ties with the anime industry, and I wonder what he's doing these days.

Masao Iizuka & Ryosuke Takahashi — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 6

Iizuka: If anything, I'd say Shibuyan was the type who would rather be making cult shows that focused purely on the quality of the works, the quality of the technique and visual expression, rather than amateurish commerce and products. He couldn't do it all by himself, but he could do it with the help of other people. So he could be a good producer when he was blessed with the right work or the right situation, but... he had trouble with the limitations of commercially based programs.

Takahashi: At Sunrise, Mr. Shibue and Mr. Iwasaki both had the same producer credit...

Iizuka: In the true sense, Mr. Yamaura was Sunrise's producer. The people who Sunrise credited as producers were production managers or production supervisors. Or, if they were at Toei...

Takahashi: They'd be line producers?

Iizuka: That's right. In the planning and setting stages, they had to borrow Mr. Yamamura's wisdom. Then once the series entered production, they relied on the setting manager and literature manager, so if anything they were just managing the production process.

Yasuhiko Yoneyama likewise left the company at an early point.

Masao Iizuka & Ryosuke Takahashi — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 6

Takahashi: The one person I don't know much about is Mr. Yoneyama. You've said that, at first, it was Mr. Yoneyama who asked you to help out as a side job. What was he like, and what did he do at Soeisha? Was he in sales?

Iizuka: Sales and publicity. He invited me to join, but I couldn't get involved. Then he asked me to do some 0-Tester cels as prizes for Kansai TV... During and after work at Mushi Pro, they'd kidnap me in Iwa-chan's car. (laughs)

Takahashi: I socialized more with him after he left. He's the kind of classy, good-natured guy that's rare in anime. His sake's not bad, either.

Iizuka: That's because he was raised well.

Takahashi: Yeah, he's well-bred.

Iizuka: Right.

Takahashi: But he left relatively early...

Iizuka: That's because his father asked him to take over the family business.

Kiyomi Numoto in 2002, when he was interviewed for the "Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream" series.

Kiyomi Numoto, the last of the founders to join the new company and the first to leave, was also the only one with any direct animation experience. After moving into a management position at Mushi Pro, Numoto was responsible for the company's animation training school, and he initially played a similar role at Soeisha. However, he left the company in 1973 during the planning of its second series, 0-Tester, to take a position at the toymaker Takara.

Ryosuke Takahashi — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 4

When I joined Mushi Pro, Mr. Numoto was an animator in charge of the animation department. He was only one year older than me, but he was earning three times as much, so he often took me out for drinks. Once I was drunk, he'd let me stay at his place, where I enjoyed looking at his extremely artistic collections of nude photos. For the sake of his reputation, I should add that these were very expensive Western books of art photography, which he used for drawing practice.

Kiyomi Numoto & Ryosuke Takahashi — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 4

Numoto: I was actually the last of the seven to join.

Takahashi: Oh, really?

Numoto: At the time, Mushi Pro was working on Belladonna of Sadness. But when things are like that, no matter how you look at it, spending more money doesn't make the work any better... They kept pushing back the schedule, and spending as much money as they possibly could, saying that they no longer had any choice. At the time, I was in charge of all the animation, so I was swamped with retakes and revisions! There were all these outrages, and all this loud complaining. I didn't want to do it anymore, so I wrote a letter of resignation and stopped going in to work... That's the point at which they approached me.

Masao Iizuka & Ryosuke Takahashi — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 6

Iizuka: Mr. Numoto was originally an animator. He got as far as second key animation. I thought after that he'd become a full key animator, but instead he became a manager at Mushi Pro. I guess that was his inclination. So when he joined Sunrise, he of course managed the animation staff and taught them his technical knowhow. Then, eventually, he went to Takara. The fact that Mr. Numoto was at Takara was one of the reasons Sunrise was able to become independent later on. But if it weren't for Mr. Yamaura... We wouldn't have been able to come up with a plan to meet that opportunity.

Takahashi: When Mr. Numoto was at Mushi Pro, ever since he was young, he attracted fierce criticism and his enemies hated him. But I got on well with him, and he always looked after me. He'd take me out for drinks, and even let me stay at his place. He was a passionate person, and stubborn in the best possible way. Although Mr. Numoto didn't end up staying at Sunrise, even on the outside he was an essential person in Sunrise's history.

Iizuka: Indeed. After all, at the beginning, Sunrise didn't have anyone with animation knowhow... They had three people from sales, and then four from production.

Takahashi: Mr. Numoto was directly responsible for putting Mr. Yasuhiko in the animation department at Mushi Pro. I once heard Mr. Numoto say "That guy's a genius."

Despite his early departure from Soeisha, Numoto continued collaborating with his former comrades.

Kiyomi Numoto & Ryosuke Takahashi — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 4

Takahashi: After you left, Mr. Yamaura took over the planning.

Numoto: Right. But strictly speaking, Mr. Yamaura was a planning coordinator. It's a slightly different idea. When it came to things like design, as Sunrise started doing original works, I ended up supervising Dougram, Votoms, Dunbine, and so forth up until the middle. Zambot 3, Gundam, and so forth also incorporated my toy knowhow. I stopped for a while after that, but then Samurai Troopers was my plan once again.

Takahashi: I see. I helped with that a little, too. You see, I'm always helping out a bit here and there.

This close cooperation with toymaking sponsors would become an essential element of the distinctive business model that the company gradually evolved.

Determined not to repeat the mistakes they'd seen their superiors making at Mushi Pro, Sunrise's founders decided to keep creators out of management roles. In fact, the creative staff wouldn't be employees at all. Whenever new projects were approved and production began, tasks such as direction, writing, design, and animation were entrusted entirely to freelancers and subcontractors. Takayukii Yoshii, the company's fourth president, discusses Sunrise's philosophy in his introduction to "Gundam-Mono: The Men Who Made Gundam."

Takayuki Yoshii — Gundam-Mono: The Men Who Made Gundam

—This is something Mr. Yoshikazu Yasuhiko said, but since Sunrise was created by people who'd experienced the failure of Mushi Production, their first priority was to ensure the survival of the company no matter what.

That's right. And of course, it's only natural that their experiences at Mushi Pro would be reflected in various ways. I think one of the things he's talking about is the rule that "creators shouldn't be involved in management." Though Mushi Pro was a production company, it was more passionate about the creative aspects of the works than about costs, schedules, and production management.

Ryosuke Takahashi makes a similar point in comparing Sunrise to Madhouse, another company founded by refugees from Mushi Pro.

Ryosuke Takahashi — Sunrise World Creator Interview 15

Sunrise decided not to put the creators at the center of the company. They were people who'd seen from Master Osamu Tezuka that creators can run wild when they're making things. Madhouse was a company centered on creators like Mr. Dezaki and Mr. Masami Hata. But Sunrise's approach was that when there was a job to do, they'd contract the creators individually for each work.

Over the years, Sunrise would become known for developing its own original works, rather than simply adapting existing manga properties. But Yoshii—like the company's founders— characterizes this not as a creative preference, but as a practical necessity for the sake of financial survival.

Takayuki Yoshii — Gundam-Mono: The Men Who Made Gundam

Sunrise was making a late entry into a field where there were already many long-established production companies. The approach of taking an existing manga work and turning it into anime was also well established at the time, and since there was also a continuity in the broadcasting time slots, we couldn't jump in there after the fact. So we couldn't follow the normal animation business model, but as we were wondering what to do, we found a way to link up with sponsoring toymakers and create works to sell their products, which you could politely describe as "original works."

The fact we started out independently producing works using that method ultimately led to the tradition of Sunrise working with original stories. But that wasn't something we chose because we wanted to, but because we had no alternative.

One benefit of creating original works, rather than adapting existing ones, was that royalty payments from merchandising would flow to the animation company itself rather than an outside creator. Since the debut of Mushi Pro's Mighty Atom in 1963, merchandising income had become a major factor in the business of anime. In "Gundam-Mono: The Men Who Made Gundam," Masao Iizuka sums up the evolution of anime merchandising as follows:

Masao Iizuka — Gundam-Mono: The Men Who Made Gundam

—Was it Tohokushinsha that came up with the idea of this kind of character business, where you create programs with merchandising in mind from the beginning?

It all started with Mighty Atom. Until then, pretty much all you had were the Disney characters and Fujiya's Peko-chan. Then, with Atom, a manga character became recognized throughout Japan through the powerful medium of television. Based on that, a business model was established which extended into a variety of merchandise.

But at the time of Atom, this merchandising mainly consisted of printed media. Rather than merchandise of the characters themselves, they were products with the characters printed on them. The main sponsor, Meiji Seika, was just releasing caramels and chocolates with Atom on the packaging, but they sold like hotcakes. The results were so good that they eventually overtook Morinaga & Company as the industry leader.

—Until Atom, the procedure was to establish a character on broadcast TV, and then use that character to sell merchandise. This merchandising was mainly printed media, but with Thunderbirds, that shifted to selling the characters themselves, in other words three-dimensional toys rather than things with characters printed on the surface.

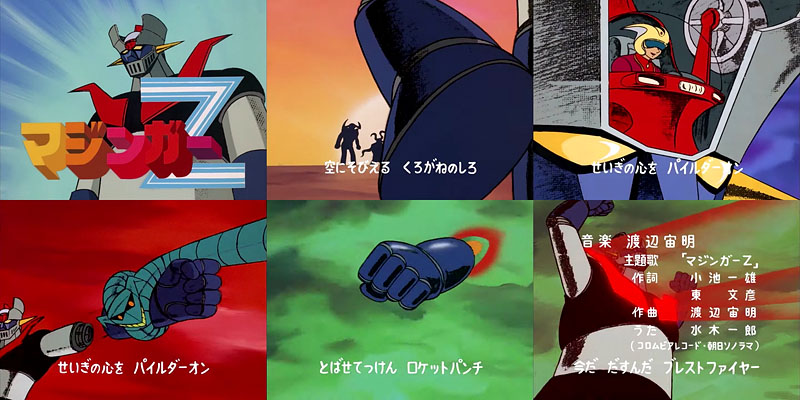

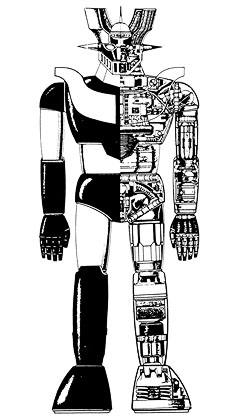

That's right. Now they had toymakers as sponsors. Then a work appeared in 1972 that marked a revolution not only in the quality of the work, but in the business model of the animation industry itself. This was Toei Doga's Mazinger Z (1972). It's no exaggeration to call this work an anime produced with a complete focus on toys as the main form of merchandising, and it was hugely successful. Or at least that's what Toei Doga intended, but perhaps the original creator Mr. Go Nagai had other ideas.

One factor was that societal conditions had developed to the point where products like that could appear. Previous character toys had generally been tin toys, and the technology to turn them into higher-quality products didn't yet exist. When these were released in the form of heavyweight figures like the Mazinger Z Chogokin, they were a real hit. These were actually cast from ordinary zinc alloy, but their weight perfectly matched a child's image of a robot.

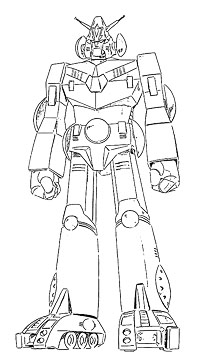

The 1972 series Mazinger Z, produced by Toei Doga and Asatsu based on a concept by Go Nagai and his production company Dynamic Pro, pioneered the genre of giant robot anime. In addition to its direct sequels Great Mazinger and UFO Robo Grendizer, the success of Mazinger Z inspired a flood of imitations in the following years.

The title robot shows off its various gimmicks in Mazinger Z's opening credits, which describe it as "a fortress of iron, towering into the sky."

Mazinger Z setting art. The Hover Pilder that serves as its cockpit, and the Jet Scrander support mecha, prefigure similar gimmicks in later Sunrise robot shots.

Left: A 2024 reissue of the "Jumbo Machineder" Mazinger Z released by Bandai's Popy subsidiary in 1972. This huge toy stands 600mm (about two feet) tall.

Right: A 1999 reproduction of the original 1974 "Chogokin" Mazinger Z, cast from heavyweight zinc alloy. Images courtesy of CollectionDX, whose in-depth review you can read here.

During the four years that passed between the birth of Soeisha and its tranformation into Nippon Sunrise, the newborn company would develop a business model in which it collaborated with toy company sponsors to create original works, then claimed a share of the merchandising sales in the form of royalties. For now, this royalty income would be going to Soeisha's parent company, Tohokushinsha.

Masao Iizuka — Gundam-Mono: The Men Who Made Gundam

—I gather that when you're creating original works, you make the main robot first.

That's right. At Sunrise, the robots come first. (laughs) It all starts with creating a toy—that is, a robot—that the main sponsor can make money selling.

—Then you create the worldview setting and decide on the cast of characters, and finally you put together a rough story. After that, the content of the actual work is up to creators such as as the series director and scriptwriters. Of course, the director and scriptwriters might be participating even before that, and you're coming up with ideas together. Is it fair to say that's the process by which they're made?

Exactly. That kind of process isn't necessary when it's based on a preexisting original work, but the drawback is that then you have to pay royalties to the original creator. With our own originals, all of that becomes income for the company, which is appealing in business terms. But unlike with a preexisting work, there's a definite risk that it won't be accepted in the marketplace. No matter what, the tastes of the creator will always come to the forefront, and there's a possibility they may not be aligned with the trends and demands of the public.

The animator, character designer, and manga artist Yoshikazu Yasuhiko, who worked on many of the company's early giant robot series, observes that this sponsorship arrangement gave Sunrise a considerable amount of creative freedom.

Yoshikazu Yasuhiko — Motion Picture King Vol.7

I think it's still like this now, but with robot anime, the sponsors don't interfere at all in the content of the story. The important thing is what kind of product they're going to sell, so they don't care about anything except concepts like how it combines or transforms. "Come up with the story on your own," they'll say. What a world, eh? (laughs)

And as Takayuki Yoshii points out, it also created a slightly unexpected incentive structure for the company.

Takayuki Yoshii & Gundam-Mono: The Men Who Made Gundam

—In that case, putting it in extreme terms, Sunrise could consider a work successful as long as the sponsor's toys are selling, even if it doesn't get audience ratings.

That's the first priority. With normal animation, you try various things to get the ratings the TV station wants. But in the case of Sunrise, first and foremost it's about accommodating orders from the sponsors.

Even when you're turning an original manga into an anime, I suppose you have creative restrictions such as "we have to make it just like the original story." When Sunrise was making its own original works, the sponsors had their demands, and there were the constraints of production management. But as strong as those restrictions were, there was an equally increased range of creative freedom.

I think that's a balance that came about quite naturally. If it were only about stronger restrictions, the creators would have lost their motivation. But even though there were a lot of constraints, as long as you met them, you could do whatever you liked. I think that balance was important.

It took some time for this model to evolve, however. At the beginning, the newly established Soeisha and its founders had only one focus—survival.

The fledgling company got off to a slow start, producing only two TV series during its first two-and-a-half years of operation. The first of these was Hazedon, which made its broadcast debut in October 1972, just one month after Soeisha and Sunrise Studio were formally established.

ハゼドン

ハゼドン| TV BROADCAST | |||

| Fuji TV • Thursday 7:00-7:30 PM October 5, 1972 to March 29, 1973 (26 episodes) |

|||

| MAIN CREDITS | |||

| Planning • original story | Video Client | Original plan | Hajime Yagurazawa |

| Key art | Haruyuki Kawashima | Coordinator | Michio Shinohara |

| Chief director (チーフディレクター) |

Osamu Dezaki (ep.1~10) Fumio Ikeno (ep.11~26) |

Setting manager | Masao Maruyama |

| Character design | Toshiyasu Okada (ep.11~26) |

Animation director | Kazuhiko Udagawa |

| Art director | Katsumi Bando |

Director of photography | Sumio Takahashi Kasami Kitagawa |

| Sound director | Toshio Sato |

Production manager (制作担当) |

Yoshinori Kishimoto Osamu Hirooka |

| Production | Soeisha, Fuji TV |

||

| ADDITIONAL CREDITS | |||

| Production cooperation | Sunrise Studio, Wako Production | ||

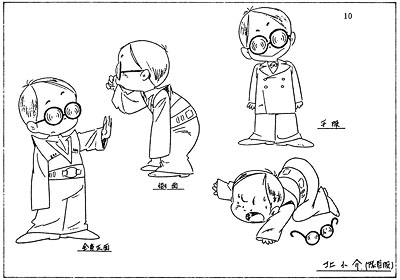

Quite unlike the sci-fi action works for which Soeisha and Sunrise would later be known, this debut series was a lighthearted cartoon about the adventures of a little fish and his undersea friends. The 1997 "Sunrise Anime Super Data File" describes Hazedon as follows:

Fish of all kinds live together in an undersea world. Hazedon is a young goby who sets out on a journey to the South Seas, wearing a seashell pendant that was a memento of his mother, to keep his promise to become the strongest fish in the world. Along the way he meets the mermaid Shiran and the puffer fish Puyan, who join him as he continues his journey.

In the first work whose production Sunrise was involved in. Nonsensical gags and romantic comedy unfold within a fairytale style and worldview. Though this work was aimed purely at children, Shiran's strangely sexy design was quite memorable.

In his "Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream" interview series, Ryosuke Takahashi describes this project as a gift from Fuji TV to its longtime partners, using the Japanese term 御祝儀作品 (goshūgi sakuhin) to liken it to the cash present given to a newly married couple.

Scenes from Hazedon's opening credits.

In any case, plunging straight into the production of a weekly series required Sunrise Studio—the production side of the new business—to rapidly assemble a staff. Yoshinori Kishimoto, one of Soeisha's seven founders, served as president of Sunrise Studio and Hazedon's producer, with his fellow Mushi Pro veteran Katsumi Bando as art director. They were aided in their time of need by two founders of the Madhouse studio, with Masao Maruyama supervising the scripts and the legendary Osamu Dezaki as the initial director.

Left: Katsumi Bando and Masao Maruyama in 2002, when they were interviewed for the "Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream" series.

Right: Osamu Dezaki, prior to his death in 2011.

The core team at Sunrise Studio was very small. In Kiyomi Numoto's account below, "Kicchan" and "Marutan" are nicknames for Kishimoto and Maruyama.

Kiyomi Numoto — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 4

Sunrise Studio began with Kicchan, Marutan, and myself. Marutan was doing the scripts, so he'd bring in his work when it was finished, but it was Bando who was most often in the studio. Kicchan was in charge of production, Marutan was writing, I was doing everything from drawing to finishing, and Bando was doing the backgrounds. That's how we did Hazedon.

Masao Iizuka — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 6

In the beginning, Kicchan (President Kishimoto) was the only production person... During Hazedon, their president Kicchan was doing the production work himself. He laid out all the cuts on the floor.

The new studio, which would later become Sunrise Studio 1, was a rented space on the second floor above a coffee shop called "Yutaka."

Ryosuke Takahashi — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 6

This was the kind of old-style coffee shop that's almost disappeared from the Tokyo Metropolis. Since it was right underneath the studio, and the studio itself didn't have space for a conference room, we held all our meetings and conferences here. I also drew and revised storyboards, thought things over, and ate my meals here. It was really a great help.

Later on, it became a record store, a video store, and then a game corner, and I think it's now a florist... The public bathhouse behind it, Daishiyu, was also very helpful, but I hear it's gone out of business and the site is now a vacant lot. It's sad, but I'll have to take a peek next time.

Katsumi Bando & Ryosuke Takahashi — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 8

Bando: The initial Sunrise was a studio above Yutaka, and I went to see it with Kicchan. Anyway, the floor was really uneven.

Takahashi: That's terrible.

Bando: Bando: Yeah. So we pulled up the flooring, and put something under it to make it more stable. Kicchan and I brought in the desks and everything else all by ourselves.

Ryosuke Takahashi describes art director Katsumi Bando as "the industry's human resources manager," and he apparently played a key role in populating Sunrise Studio with production staff. In particular, Bando was able to reunite many of the staffers who had worked under Kishimoto on the 1971 TV series Wandering Sun.

Katsumi Bando & Ryosuke Takahashi — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 8

Bando: When they left Mushi Pro, both Marutan and Kishimoto were in production. Marutan had just formed his own production company, and as it turned out, there was nobody over at Kishimoto's place...

[Takahashi:] Sunrise and Madhouse, now two of the liveliest and most active production companies, were born in 1972. As for the reason Sunrise was unable to gather production staff, the previous year, Mr. Kishimoto had been working on Wandering Sun (April 8 to September 30, 1971). Then Mr. Maruyama did Kunimatsu-sama no Otoridai (October 6, 1971, to September 25, 1972), and ultimately the Kunimatsu team moved directly over to Madhouse. My guess is that, since it had been about a year since Mr. Kishimoto's Wandering Sun team was disbanded, they'd all scattered in the meantime. Mr. Bando's following testimony supported this idea.

Bando: I just remembered this, but Iwa-chan came in a little later. Since he still had some things to sort out at Mushi Pro, he wasn't there during Hazedon. So Kicchan said "Bando, please do something!" I persuaded Masaaki Sakurai, Hiroshi Otake, Susumu Ishizaki, and so forth, who hadn't yet decided where to go, saying "Come and back up Kishimoto."

But they didn't have a leader... As production assistants, their skills weren't that high. Osamu Hirooka was wandering around somewhere, so I said "Hirooka, come help out a little." That's how Hirooka ended up working on Hazedon.

[Takahashi:] Masaaki Sakurai, Hiroshi Otake, Susumu Ishizaki, and everyone else Mr. Bando had mentioned were all connected to the Wandering Sun team.

As it turned out, Osamu Dezaki's tenure on Hazedon was fairly short, and he left the production after ten episodes.

Ryosuke Takahashi — Sunrise World Creator Interview 15

Unlike today, it was an era when there wasn't any money to create works. So it's a question of how you feel about having no money. Since Mr. Dezaki was a creator, he went in the direction of "I want to make it like this" and "I want to do that." But Soeisha's priorities were schedules and budgets. As a result, Mr. Dezaki lost interest along the way, saying "This isn't a production company I can stay with," and he left in the middle. Though Mr. Dezaki had been sent over from Madhouse to Soeisha, he ended up going back.

I'm not sure how Hazedon was made after that, but its broadcast had been decided even if they didn't have a series director, so the production probably continued under the guidance of the directors of each individual episode.

Soeisha and Sunrise Studio were now in business. But it wasn't until October 1973, a year after Hazedon's debut, that the new company finally managed to get another show on the air.

0テスター

0テスター| TV BROADCAST | |||

| Fuji TV • Monday 7:00-7:30 PM October 1, 1973 to December 30, 1974 (66 episodes) |

|||

| MAIN CREDITS | |||

| Planning | Kansai TV Tohokushinsha |

Original story | Yoshitake Suzuki |

| Music | Naozumi Yamamoto | Mechanic design & concept | John Dedowa |

| Character design | Munehiro Minowa | Chief director (チーフディレクター) |

Ryosuke Takahashi |

| Animation director | Kazuo Nakamura (ep.1~39) | Art director | Jiro Kono |

| Director of photography | Horofumi Kumagai (ep.1~39) Yukuhiko Sano (ep.40~66) |

Recording director | Toshio Sato |

| Literature manager | Masao Tokumaru (ep.1~39) Eiji Yamaura (ep.40~66) |

Producer | Hiroshi Miwa (Kansai TV) Yoshinori Kishimoto |

| Production | Kansai TV, Soeisha | ||

| ADDITIONAL CREDITS | |||

| Cooperation | Crystal Art Studio | Production cooperation | Sunrise Studio (ep.1~39) |

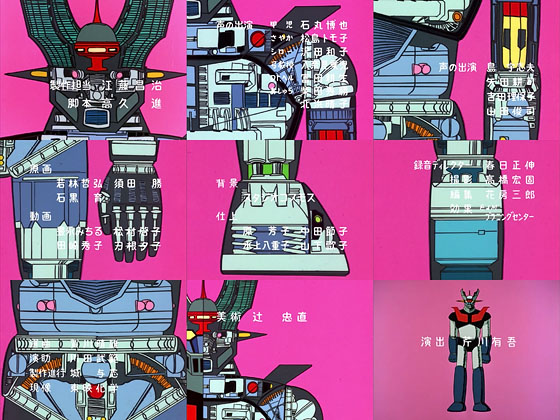

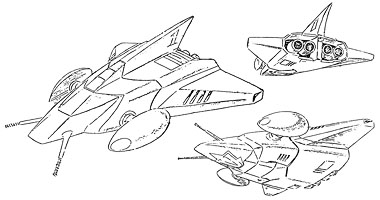

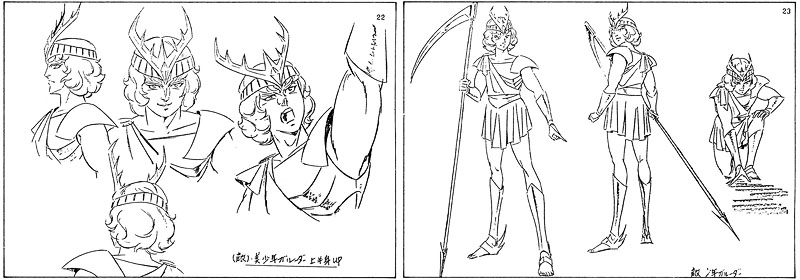

Soeisha's second work, pronounced "Zero-Tester," is often characterized as an anime version of Thunderbirds, a 1965 science fiction TV series created by Gerry and Sylvia Anderson for British television. The "Sunrise Anime Super Data File" describes 0-Tester as follows:

In 2100 A.D., Earth is targeted by a mechanized race called the Armanoids. Responding to a series of space accidents, Dr. Tachibana of the Future Science Development Center creates the specialized mecha Tester-1 through Tester-5, and assembles a team of pilots to operate them. These people, who protect the Earth in extreme situations with zero life support, are known as the 0-Testers.

This work was created aiming for an effect like that of the British TV puppet show Thunderbirds. That influence can be seen in the stories about space accidents, and the transforming and combining Tester mecha. However, it wasn't well received by younger age groups, so after episode 39 it was retitled 0-Tester: Save the Earth! and the focus changed to confrontations with the giant monsters known as the Gallos Seven.

Thunderbirds began airing in Japan in 1966, and proved to be a huge success in terms of both audience ratings and merchandise sales. The plastic models released by Imai—and subsequently reissued by Bandai—were particularly popular. Tohokushinsha, which produced the Japanese version of the series, had also secured the Japanese licensing rights and thus made a lot of money from the Thunderbirds phenomenon. So it was only logical that Tohokushinsha's president would instruct his subsidiary Soeisha to create a similar series for its followup work.

Kiyomi Numoto & Ryosuke Takahashi — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 4

Numoto: He has a bad reputation, but President Banjiro Uemura's words carried a lot of weight. He told us to make money. Nobody ever talked about making money in the Mushi Pro days, and if you said something like that, people would despise you. (laughs)

Takahashi: Well, there was that kind of atmosphere.

Numoto: But we'd learned firsthand that we couldn't keep going if we didn't make money. In that sense, he was very perceptive. President Banjiro didn't know anything about ideas like mecha design, but he knew Thunderbirds had sold well. He explained that in detail, and he already knew that Japan would follow the same path in the future.

Takahashi: Wow, not bad.

[Takahashi:] Mr. Banjiro Uemura, the head of Tohokushinsha, was something of a self-made man. It's commonplace that people like that are fiercely criticized, and because of Mr. Uemura's slender build, you'd often hear people inside and outside the company calling him things like "that crow Banjiro!"

Numoto: So I thought about what new things we could do in a Japanese version of Thunderbirds, and 0-Tester is what I came up with. It was the starting point of Sunrise's original works. I can be very clear about that, since I was responsible for planning it.

Takahashi: Wasn't Hazedon the first one? Anyway, I was pretty sure Hazedon was purely a gift from Fuji TV. So after that, Sunrise discussed what they should make next, and I figured that was 0-Tester. But it wasn't Sunrise's seven founders who first suggested that, but President Banjiro?!

Numoto: It was Ban-chan.

Takahashi: So it was President Banjiro Uemura after all!

Numoto: Although President Banjiro didn't tell us to do SF, just something profitable like Thunderbirds. Then we tallied up all the appealing things about Thunderbirds, so it was only natural that we decided to make a Japanese version of it.

Masao Iizuka — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 6

Mr. Yamaura said that Mr. Uemura told him to make an animated version of Thunderbirds because the Thunderbirds toys sold so well... While Mr. Yamaura was walking back from Fujimidai Station, he saw an appliance store by the railway tracks, and just as he was trying to decide on a title he noticed the word "tester." There were issues with calling it 1-Tester, so he extended it to "0-Tester." (laughs)

Mr. Uemura's line of business was buying foreign TV programs and then selling them in Japan. He'd even created a studio for dubbing the sound. I thought he was an amazing and far-sighted entrepreneur. And 0-Tester turned a profit, too.

Kiyomi Numoto — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 4

Bandai was supposed to merchandise 0-Tester on a much larger scale, but right at that moment the price of materials skyrocketed due to the oil crisis, and toys are basically just lumps of plastic. So the plan was scaled down, but 0-Tester still sold well.

The series did indeed prove reasonably successful, as did Bandai's toys and plastic models. After its rebranding as 0-Tester: Save the Earth!, the broadcast run was extended to a total of 66 episodes.

Scenes from 0-Tester's opening credits, and the new title introduced with episode 40.

Soeisha's lineup of reliable freelancers continued to expand as 0-Tester was taking shape. Some of these were former comrades from the Mushi Pro days, while others were up-and-coming new talents who would play major roles in future Sunrise works—and in the history of anime.

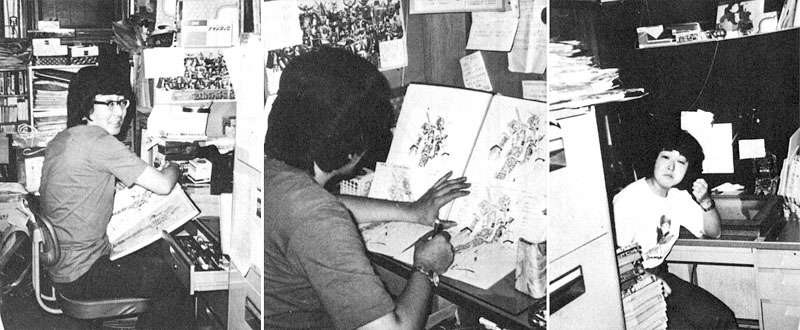

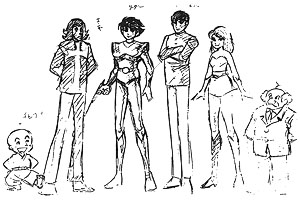

Left: Haruka Takachiho in 2002, when he was interviewed for the "Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream" series.

Right: Kenichi Matsuzaki in 2002, from the "Gundam-Mono" interview book.

Center: Kazutaka Miyatake in 2023, when he was interviewed for the Sunrise World website.

Before leaving to join the toymaker Takara, Soeisha founder Kiyomi Numoto made contact with a group of college science fiction fans who would later be known as Studio Nue.

Kiyomi Numoto & Ryosuke Takahashi — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 4

Takahashi: You left both Soeisha and Sunrise Studio very early on. At what point did you leave? Was it before 0-Tester entered production?

Numoto: Yeah. After we'd finished all the planning.

Takahashi: I'd like to hear a little more about that, please.

Numoto: There was somebody called John Genowa or Dedowa, I forget which, who did mecha design for Thunderbirds. On 0-Tester, where I was provisionally responsible for the mecha design, I began by contacting Mr. Minowa, an animator who was then at Tatsunoko, as well as the predecessor to Studio Nue.

At the time, Nue hadn't yet become "Crystal Art," and it was still just a bunch of people from an SF fan club. So I gathered them at a coffee shop in Ikebukuro, and told them "I'll provide the coffee and cake, if you'll tell me all about SF." And yikes, about thirty of them showed up, and they talked and talked and talked... That's how it happened.

One of the group's leaders was Haruka Takachiho, who would go on to become a prominent science fiction author. In his interview for the "Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream" series, Takachiho gives a detailed account of the group's origins, its early career as Crystal Art Studio, and its eventual decision to dissolve and reconstitute itself as Studio Nue in order to escape an awkward social situation.

Haruka Takachiho & Ryosuke Takahashi — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 10

Takachiho: I think it was around 1972, but Naoyuki Kato, Kenichi Matsuzaki, Kazutaka Miyatake... all of them except me were about to graduate from university or vocational school, and we'd started discussing what to do about finding jobs. At a meeting of the dōjinshi "SF Central Art"—

Takahashi: Eh?! Not Crystal Art? It was Central Art?

Takachiho: The dōjin club Matsuzaki was running was called "SF Central Art," but the title of the club bulletin it published was "Crystal." We'd meet once a week at a coffee shop in Ikebukuro, and we'd all talk about "SF is like this" and "Art is like that."

I was still in my second year of university, but the main members all had to think about getting jobs... As they were discussing where they should find employment, I casually suggested "Rather than joining a company and being constrained, wouldn't you rather try doing jobs that make use of SF?" They all said "That would be fun, but first let's check and see whether jobs like that exist." If the jobs didn't exist, then we couldn't do that, right?

Naoyuki Kato had a classmate working at Sunrise, who asked whether we'd like to do mechanic design for their next new program. By that point, Miyatake had already been working a lot on "robot internal diagram" orders for Ishimori Production and Dynamic Production. If it was an animated mecha show, we thought we could do it... So that was the first one. Another was an approach from the SF veteran Mr. Masahiro Noda, saying "I'm going to be making an education program for preschoolers, so I can throw some illustration work your way."

...So, for the time being, we decided to form a company to do those two jobs (since Fuji TV wouldn't have been able to work with us unless we were a business organization). We averaged together "SF Central Art" with "Crystal" from the club bulletin, established a limited company called "Crystal Art Studio," and started doing business... I think in Higashi-Nagasaki? I feel like that was probably at the beginning of 1973.

Takahashi: The new job was 0-Tester, right?

Takachiho: There were four or five of us, but we all went as a group and visited each place in turn. We went to Fuji TV about Hirake! Ponkikki. They told us to do some drawings first and bring them in. "Right, right," we said.

Next we went to Sunrise Studio, and Mr. Numoto showed up to tell us about mecha design. We didn't know anything at all about animation or anime, but we'd been studying things related to SF for a long time, and we also understood scientific subjects, so our main topic of discussion was how to reconcile all these aspects. Then we turned in some sample drawings (we all had to work together to turn the useless, terrible drawings by a certain foreign designer into something decent)... and we kept on working like that.

Meanwhile, we divided up the business responsibilities. We decided Matsuzaki would be responsible for Sunrise, and I'd be in charge of Hirake! Ponkikki. So I didn't have much to do with Sunrise at first...

Takahashi: I'm sure I first visited you when you were in Higashi-Nagasaki.

Takachiho: At that point, everyone was sleeping there. We didn't have our own rooms, and all the members would just lie around the company office, like in an anime studio.

Takahashi: You must have been associated with many different places, but I only knew about Nue through Sunrise. So what was Nue's work like? Was Sunrise a big part of it?

Takachiho: No, Hirake! Ponkikki was the biggest. At any rate, it kept us busy. That's what led to us becoming Studio Nue. The Ponkikki workload was steadily increasing, but the things we drew for it didn't become hits like "Oyoge! Taiyaki-kun." (laughs) There was so much detailed work, and the fees never increased... When we created the company, the founding ethos was "let's do SF," so this situation wasn't quite...

Meanwhile, Ponkikki was gradually overwhelming us. If this kept up, we'd never be able to do what we'd set out to do. But it would be hard to say "Please let us quit Ponkikki" after all they'd done for us. We thought we might as well just dissolve the company, so we did that instead.

The Hirake! Ponkikki mentioned by Takachiho was a long-running children's entertainment program similar to Sesame Street. Launched in 1973, the program continued for 20 years. The 1975 song "Oyoge! Taiyaki-kun" became a record-breaking hit single after it was featured on Ponkikki, but clearly Crystal Art Studio's future lay elsewhere...

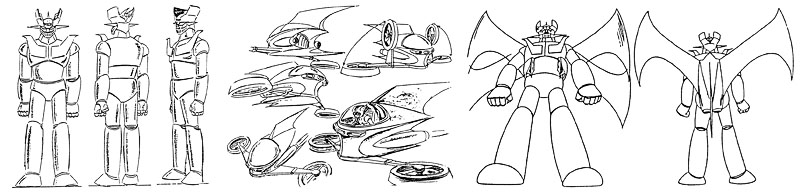

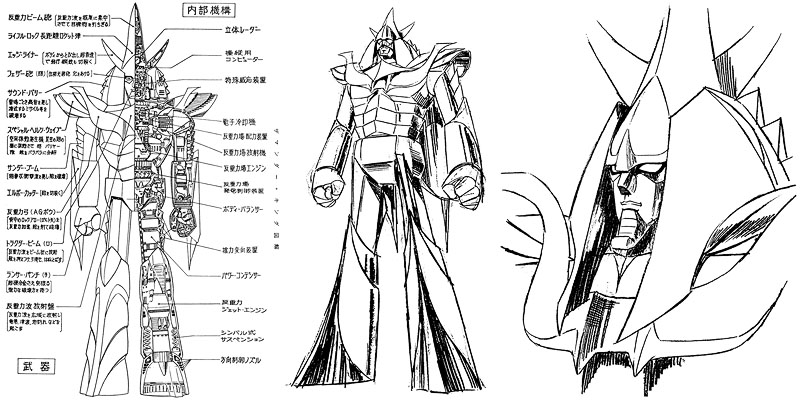

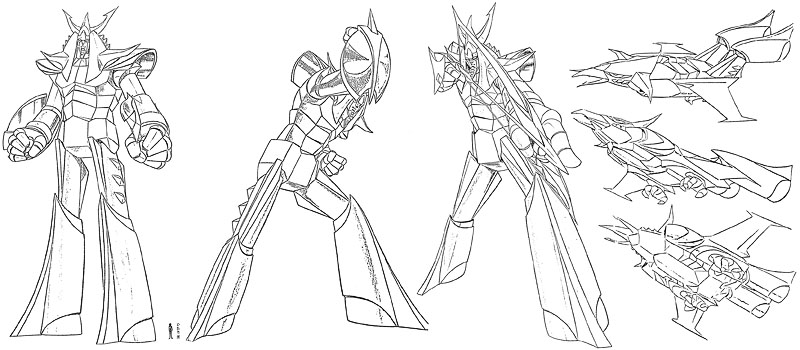

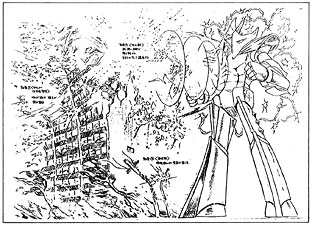

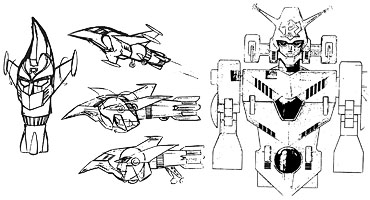

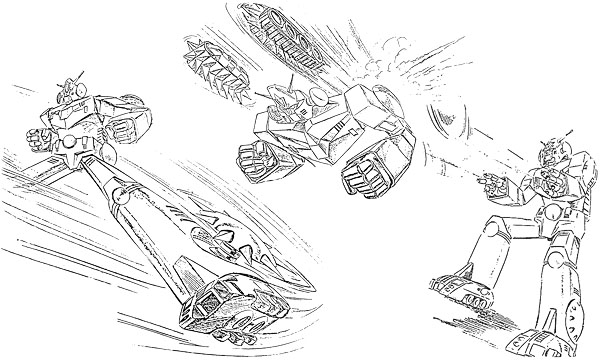

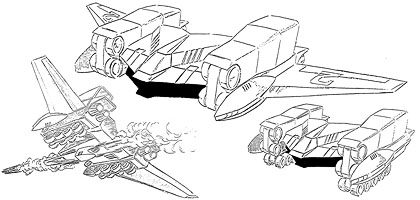

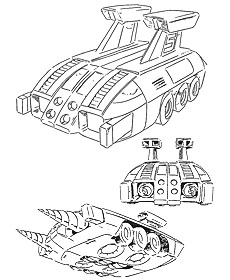

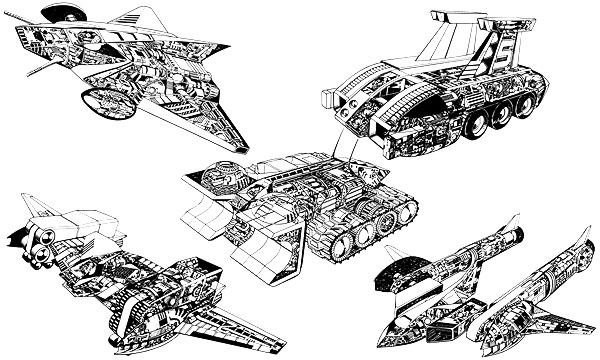

Cutaway illustration for 1972's Mazinger Z by Kazutaka Miyatake, and its depiction in the ending credits.

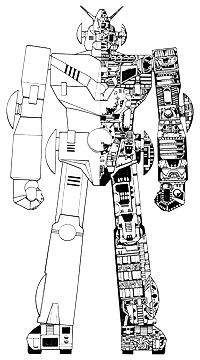

Though the mechanical design for 0-Tester is credited to a (possibly mythical) foreign designer named John Dedowa, in practical terms the designs were created by the members of Crystal Art Studio. Among them was an artist named Kazutaka Miyatake, who had made his anime debut when he was still a student by providing the detailed cutaway drawings used to illustrate the ending credits of Mazinger Z.

In an interview for the Sunrise World website, Miyatake recalls his unnerving audition with Soeisha's Kiyomi Numoto.

Kazutaka Miyatake — Sunrise World Creator Interview 19

—Mazinger Z began airing at the end of 1972. Crystal Art Studio, the predecessor to Studio Nue, launched that same year as well.

And 1972 was also the year in which Soeisha, the predecessor to Sunrise, started up. Naoyuki Kato of Nue had a senior art-school classmate there who told him they were looking for designers, so I went over there with two hundred of my design drawings. And there I met Mr. Kiyomi Numoto.

—He was one of seven members who became left Mushi Pro and established Soeisha and Sunrise Studio, right?

Mr. Numoto had very keen eyes. One by one, he looked at the designs I'd brought, and after taking in the whole picture his eyes would move as he scrutinized the key points. His gaze was very sharp. He finished looking at all two hundred of them in about thirty minutes, then gave me the order "We want distinctive mecha for the three protagonists. Please do that." He had no other requests at all. So I went home and finished up the designs.

—That's all there was to the order?

That was it. So when I designed them, I added the quirk that the aircraft piloted by the three characters combined to form a single mecha. But aircraft have broad wings and a flat shape, so I had a hard time giving them the sense of volume that kids would want when they were turned into toys. After all, it was my first professional design job.

—And the design you submitted became 0-Tester's Tester-1.

That's right, and Mr. Numoto said "We'll take it." Then he went on to say "We'll take it, but I'm keeping this to myself. I can't show such an inept drawing to the other staff."

—That's harsh.

"You have no idea how to draw," Mr. Numoto said. "You have to start by knowing how to draw. You do calligraphy, don't you?" And indeed, I'd reached the fifth dan. He told me that when working as a designer in the animation world, calligraphy techniques were actually a hindrance, so I should get rid of them.

—How could they be a hindrance?

For example, when you look at this cup sitting here, or a car parked in front of you, you ask yourself where the buttsuke is in the shape and whether it has any hane. Buttsuke and hane are techniques for writing text characters, not for designing. That had become a habit for me, so I wasn't even conscious of it.

—So that was it.

Mr. Numoto had been the head of Mushi Pro's animator training school, so I guess he couldn't tolerate the idea of abruptly putting down the point of the pencil and then pulling on it with a flick. Real objects aren't like that. The point of the pencil gently descends onto the paper, moves, and then gently rises into the air again. That's how you draw perfectly parallel lines, he said. And the human hand is designed to pivot at the wrist and at the elbow so you can draw big curves. It's no good if you just draw by following the strokes, he told me, and you have to consciously control the pencil yourself. I still remember every word Mr. Numoto said..

—And then you practiced?

Right. I drew parallel lines on straw paper until it turned pitch black, and then after I'd done my parallel line training, I'd practice radial lines. First I'd draw them from the outside into the center, and then from the center to the outside. I kept that up for about two weeks, and then he said "That's enough" and told me to draw my original design over again.

—So the design was finally officially accepted.

But when I took in my redrawn designs to show Mr. Numoto, he'd already left Soeisha. (laughs) He'd gone to join Takara, so I visited him there, and he offered me work for Takara as well. That's how I got involved with Microman.

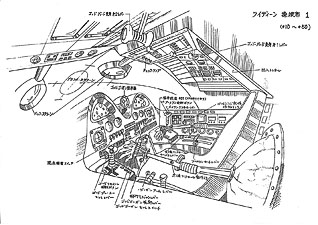

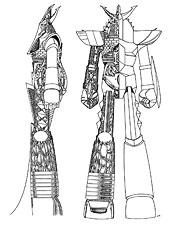

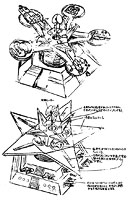

The final designs included a fleet of Thunderbirds-style specialized vehicles, led by the three-part combining Tester-1—a gimmick reminiscent of the Ultra Hawk 001 from the 1967 special-effects show Ultraseven. Miyatake and his fellow Crystal Art Studio members produced detailed cutaways and diagrams of their creations for promotional purposes, following in the tradition established by Miyatake's illustrations for Mazinger Z.

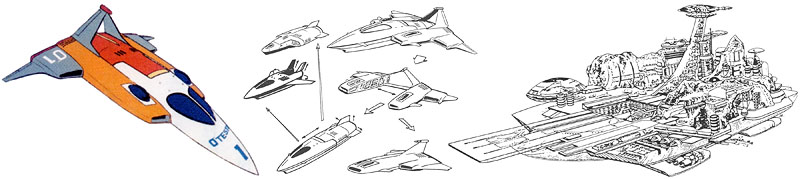

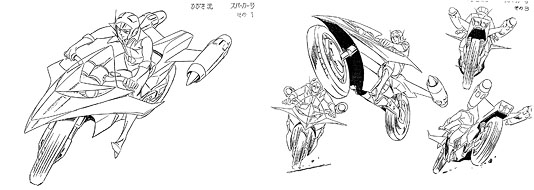

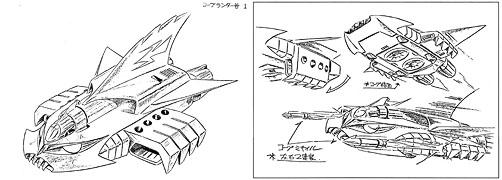

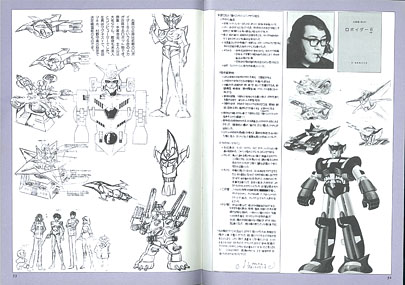

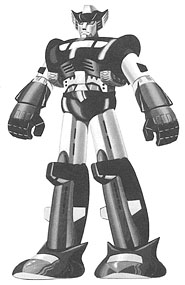

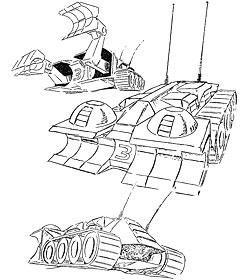

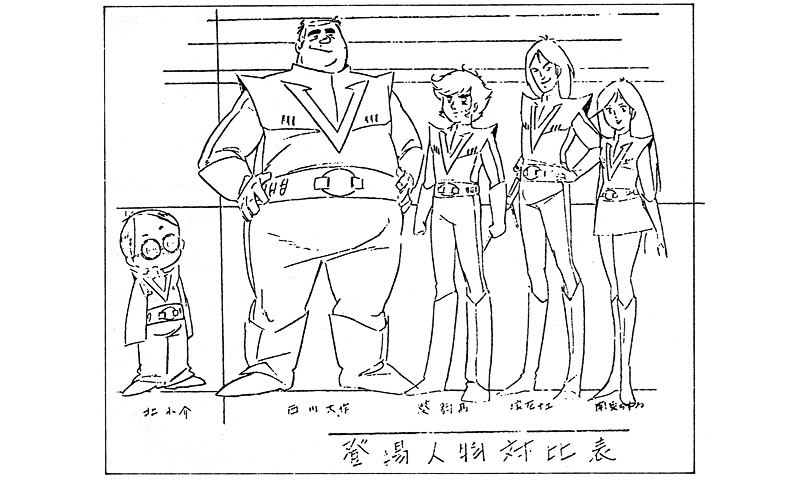

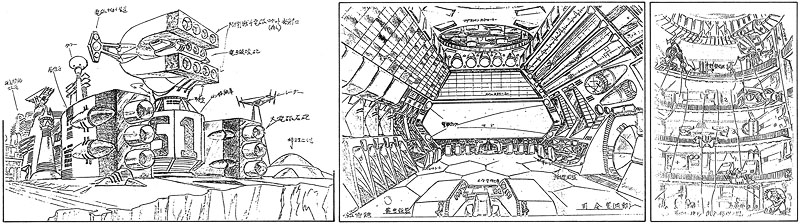

0-Tester mechanical designs by Crystal Art Studio. The original concept for the island base was by Katsushi Murakami of Bandai's Popy subsidiary.

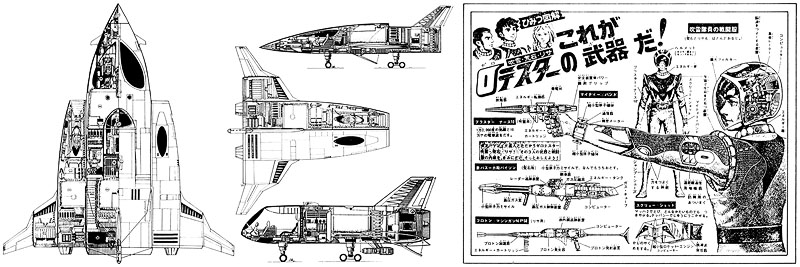

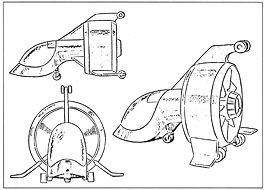

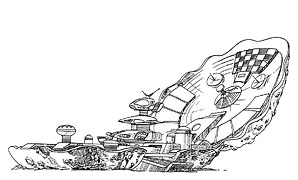

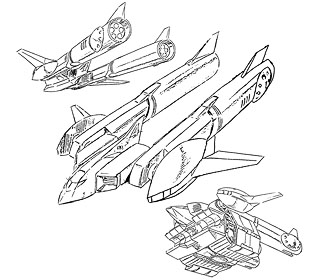

Internal cutaway views of the Tester-1 and its components by Kazutaka Miyatake, and equipment diagrams created by Crystal Art Studio for magazine publication.

With Numoto's departure, Eiji Yamaura became primarily responsible for planning the new series. He turned to scriptwriter Yoshitake Suzuki, another Mushi Pro veteran who had previously contributed episode scripts to Hazedon, to finalize the story and complete the proposal so that the project could be approved.

Left: Yoshitake Suzuki in 1978 and 1987.

Right: Suzuki in 2002, when he was interviewed for the "Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream" series.

Suzuki, also known by the alias Fuyunori Gobu which he used for episode scripts and his many "chief writer" and "series structure" credits, went on to become a mainstay of Soeisha's and Sunrise's works. His working relationship with Yamaura went back to their days at Mushi Pro.

Yoshitake Suzuki — Zambot 3 / Daitarn 3 Chronicle

I was originally at Mushi Pro, and that's where I first met Mr. Yamaura. At the time, Mr. Yamaura was in the photography department, and I was an assistant director and production assistant, so our relationship was purely professional. After that, Mushi Pro's management went awry, and everyone started leaving for other companies. I basically wanted to write scripts, so I quit Mushi Pro and began walking the path of a scriptwriter. And this may sound weird, but Mr. Yamaura and the others created their own company because they said they had to make a living. That was Soeisha, the predecessor to Sunrise.

At the time, I was writing scripts elsewhere. Then the freshly created Sunrise called me in. Before I arrived, it seems they'd brought in Madhouse's Mr. Maruyama (Masao Maruyama, currently the president of Madhouse) and the director (Osamu) Dezaki, and though I don't know much about it, I was called in as a replacement when they left Sunrise. I joined in as one of the writers on Hazedon, and at the time, Mr. Maruyama was serving as literature manager.

After that came 0-Tester, which was inspired by Thunderbirds. Because that had been a hit, Soeisha's backer Tohokushinsha wondered whether they could sell another round of similar toys, so they asked us to do it.

Suzuki's work on the 0-Tester proposal, however, took place under less than ideal conditions.

Ryosuke Takahashi — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 3

Mr. Yoshitake's pen name "Fuyunori Gobu" is inscribed on countless Sunrise works. I call him Mr. Yoshitake based on his real name, Yoshitake Suzuki, which also appears as an original creator of 0-Tester, Zambot, and Xabungle. Mr. Yamaura says that when he was a newlywed, he locked up Mr. Yoshitake in his own six-mat room and made him write a proposal in three days and nights without sleeping.

Once upon a time, I myself crashed in Mr. Yoshitake's room when he was a newlywed, spending several months there living in hell. I was working on a series that had stalled out when the producer and director both ran away, and I was going straight from writing scripts to storyboarding, over and over again. Well, whatever anyone says, he's one of the finest people in the anime world.

Eiji Yamaura & Ryosuke Takahashi — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 3

Yamaura: At that time, I'd just gotten married. We were renting an apartment less than a minute's walk from the Tachikawa Velodrome, with no bathroom and just six tatami mats of space. I remember Mr. Yoshitake stayed for three days at my place writing the proposal. Even though my wife was working as well, she had to sleep in the kitchen. We wracked our brains writing it. Under the circumstances, I think it's amazing we ended up producing more than sixty episodes of 0-Tester. But that was also a plan created through learning by imitation, right? And it was the first time everyone's role was listed in the credits.

Takahashi: From the series director and producers to the character designer, animation director, art director, color coordinator...

Suzuki's heroic efforts in putting together the 0-Tester proposal earned him an "original story" credit line. He would be similarly credited in Soeisha's Reideen the Brave and Sunrise's Zambot 3 and Xabungle.

Yoshitake Suzuki — Complete Works of Yoshiyuki Tomino 1964-1999

The reason I had myself listed as original story creator wasn't that I wanted to promote my own name in order to broaden the scope of my work. I actually had a different objective at the time. In short, back then all anime was based on preexisting original stories by manga artists. Even when the initial plan and the content of the resulting work were our own original creations, it was still standard practice to credit manga artists as the creators. But if people from the animation industry were planning and actually making the work, I wondered why we couldn't describe ourselves as the original creators.

In those days, it was manga artists who were highly regarded by the public, and the people working on anime production sites had a much lower status. We weren't really appreciated. These attitudes made us resentful and frustrated, so we fought a battle to put forward the names of people from the anime industry as original creators, in order to raise public awareness about our position. That was partly the stubborn pride of a small production company, but it was also the pride of an anime writer.

Left: Ryosuke Takahashi in 1986.

Left: Takahashi in 2002, when he was interviewed for the "Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream" series.

Right: Takahashi in 2023, when he was interviewed for the Sunrise World website.

Series director Ryosuke Takahashi would go on to have a long-running relationship with Sunrise. In addition to providing us with vast amounts of historical detail and funny gossip through his "Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream" interview series, Takahashi went on to direct landmark robot anime such as Dougram, Votoms, Galient, Layzner, and Gasaraki. By Takahashi's account, his recruitment to direct 0-Tester arrived at a point in time when he was uncertain about his future in the anime industry.

Ryosuke Takahashi — Sunrise World Creator Interview 15

I'd known the Sunrise founders ever since we were all at Mushi Production. The only one who was senior to me at Mushi Pro was Mr. (Kiyomi) Numoto, and all the other people involved in founding the company joined after I did. I guess that made me their senior, but only by a few months. Of the Sunrise founders, I was closest to Mr. (Eiji) Yamaura. Anyway, even though though they were my juniors, they were all older than me because they'd joined Mushi Pro in mid-career. It was something like that, but my memories of the time are pretty fuzzy.

—It's already been half a century.

I joined Mushi Pro in 1964, so that's more than half a century. Eventually they'd all left Mushi Pro, and I was doing various different things on the fringes of the animation industry. Rather than working on anime full-time, I'd been wandering around on the fringes of the anime world drawing manga, hanging around with people doing plays, and shooting commercials. Then, when they were producing 0-Tester, which was to be Sunrise's second work, they called me in to direct it.

Ryosuke Takahashi — Sunrise Animation 2001

The year after the company was founded (1973), Hazedon ended and all their production staff left, so they didn't have anyone at the production site. Then a senior I was close friends with got in touch with me. I hadn't yet decided whether I wanted to keep working in anime at that point, but they didn't have any other candidates for a director, and I didn't have anyone else to look after me. That's why I signed up for 0-Tester.

Ryosuke Takahashi — Sunrise World Creator Interview 15

I happened to be wavering between things at that point, and I was friendly with Mr. Yamaura and Mr. Numoto, so they ended up saying "How about that guy?" Then they called me in.

I wasn't yet established as a director back then, and I hadn't even been going in to other people's studios to direct episodes. My directing experience was all the level of individual episodes, and I wasn't a lead player. Though I worked on things like Wonder 3, Dororo, and Goku no Daibōken, I'd only been doing episode direction while surrounded by ace-class people, and I wasn't even sure whether I was going to make a living in anime. That was my situation when I was asked to do the job, so I said "I'll give it a try anyhow." In that sense, 0-Tester was like a fresh start for me in anime. Fortunately, the products did well commercially, and the broadcast run was extended.

—Were the plan and the content of the work already decided at the point when you got involved with 0-Tester?

That's right. I hadn't participated in the planning. 0-Tester was created by analyzing the structure of Thunderbirds, which had been a big hit as a special effects program, and reconstructing it for Japanese animation. By the time I joined in, the design of the mecha had been decided as well. Then I was called in at the stage where they were creating the scripts for each episode. It was an enjoyable job, and I was still young, so I pretty much never went home and just hung around the studio while I was working on it.

Takahashi's association with Soeisha was to be a temporary one, however. Despite the success of 0-Tester, he wasn't yet sure that he could make it as a director, and his confidence took a major blow from another anime series that debuted just as 0-Tester was wrapping up...

Ryosuke Takahashi — Sunrise World Creator Interview 15

Just as I was starting to feel I'd created a fairly successful work, Space Battleship Yamato started. This was still in 1974, but our broadcast started in April, and theirs in October. Watching it, I was devastated as a creator. Space Battleship Yamato was leaps and bounds ahead of the animation I was making. So I asked to be excused from directing Sunrise's next work, saying "I'm going to go back and retrain for a while." Mr. (Yoshiyuki) Tomino ended up doing the following Reideen the Brave, and I parted ways with Sunrise for the first time.

Left: Yoshikazu Yasuhiko in 1982.

Center: Yasuhiko in 2002, when he was interviewed for "Gundam-Mono" and "Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream."

Right: Yasuhiko in 2021, when he was interviewed for the Sunrise World website.

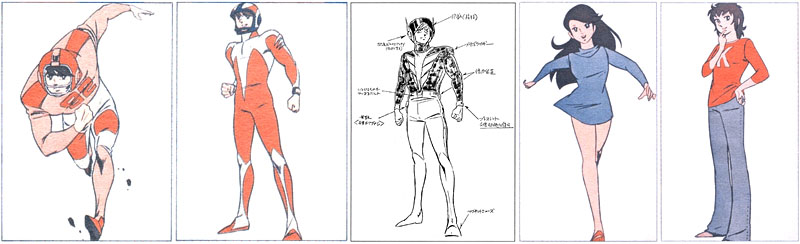

Another Mushi Pro veteran whose involvement in 0-Tester would lead to bigger things was Yoshikazu Yasuhiko. Previously a key animator at Mushi Pro, Yasuhiko found that Soeisha's contining manpower shortage gave him an opportunity to try out new roles such as animation direction, storyboarding, episode direction, and even scriptwriting—prefiguring the variety of roles he'd play in the Space Battleship Yamato series and later Sunrise works.

Yoshikazu Yasuhiko — Motion Picture King Vol.7

When Mushi Pro went bankrupt, I was wondering where to go. If I'd gone to Madhouse, they might have said "We don't need people like you." But there was someone I knew at Soeisha, so I figured they'd probably give me some work if I went there.

—What was your last job for Mushi Pro?

I think it was Little Wansa. Mushi Pro itself was running out of work, so they got the whole company together to do that.

—So there were still people at Mushi Pro?

They had loads of people. It's because they had so many people that they went bankrupt. (laughs)

—And after that, you did animation direction on 0-Tester at Soeisha.

That was a long-running work, and at first they hired me as an ordinary key animator, but I was getting fed up with all the revisions. Since they didn't have enough people anyway, they gradually started asking me to do more and more. As I came to understand this, I figured I could take advantage of their weakness and started declaring that I could do other things as well, suddenly saying "let me draw storyboards" and "I wanna direct, too."

—That experience of being an episode director must have come in useful later on.

Or rather, I said I became an animator because I couldn't be an author, but I still had a lot of lingering attachment to the idea of authorship. Many people might consider this a rude thing to say (laughs) but being an animator is pretty boring.

Yasuhiko began storyboarding for 0-Tester with episode 41, broadcast in July 1974, and debuted as an episode director with episode 46, which aired in August of that year. He continued contributing to the series until its conclusion in December 1974, by which time the planning of Soeisha's next series had begun.

Yoshikazu Yasuhiko — Motion Picture King Vol.7

—And how was it when you first tried doing storyboards?

Simply put, I thought it was easy. That's because the work called 0-Tester was also at a pretty low level. It's cheeky of me to say that, but it's a good thing, too. I couldn't say that if it had been a high-level work.

—Were you working on Space Battleship Yamato at that point?

Yamato was later on. That was after I did Reideen the Brave. I think they did about 70 episodes of 0-Tester.

—Do you feel 0-Tester was an innovative work for its time?

Well, it allowed me to do things like that. Starting with key animation, over a long period of time I was able to do various things like storyboards, scripting, and animation direction. It's said that anime doesn't have such a thing as authors, but I unknowingly went in the direction of authorship. When we did Reideen the Brave, I had a stronger awareness that was what we were doing.

With two TV series to its name, and working relationships with many energetic and imaginative creators, Soeisha had survived its first years as a newborn company. The question, of course, was what to do next.

Around 1974, a new department known as the planning office was created specifically to develop ideas for animation projects, create proposals, and pitch them to sponsors. Once a proposal had been approved and a sponsor secured, the project would then be handed off to a producer and the production work would begin in earnest.

Eiji Yamaura, who had taken over the planning duties with Kiyomi Numoto's departure, turned to another Mushi Pro veteran to back him up. In his new role as the planning department's desk chief, Masao Iizuka would become Yamaura's indispensable right-hand man.

Left: Masao Iizuka in 1980.

Right: Iizuka in 2002, when he was interviewed for "Gundam-Mono" and "Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream."

As well as helping Yamaura craft proposals, Iizuka was also responsible for gathering and archiving all the materials generated in the development and production process, from planning documents and design art to scripts, storyboards, and animation cels. This was similar to his role at Mushi Pro, where he assisted Osamu Tezuka in implementing a "bank system" which allowed animation sequences to be repurposed in later episodes.

Masao Iizuka & Ryosuke Takahashi — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 6

Iizuka: Well, in my last days at Mushi Pro, I was in a position called "planning and sales materials"... I didn't really know what that meant. (laughs) At Mushi Pro, nobody was even keeping track of the original film plates, so I was up every night doing it...

Takahashi: Organizing the film?

Iizuka: I wasn't just organizing it, I was doing everything from selling prints to placing orders with photo labs and processing cuts. (laughs) It was a total mess at the time. Some of the film plates were at Mushi Pro's headquarters, some were at Tezuka-sensei's house, some of them were at other studios (laughs), some were over at Toyo Laboratory (now Imagica)... I thought I was in no position to join some "new company," so I turned them down.

Takahashi: And that was Sunrise?

Iizuka: Right. At first, I wondered what they could do with just production and sales... (laughs) Since they didn't have any actual makers. (laughs)

Between his doubts about the new company's prospects, and his continuing responsibilities at Mushi Pro, Iizuka didn't join Soeisha until after 0-Tester had been launched and the company founders were trying to decide what to do for a followup.

Masao Iizuka — Gundam-Mono: The Men Who Made Gundam

They ended up being happy that 0-Tester was well received. But then they had to write a new proposal every week as they wondered what to do next. At that point I heard Mr. Yamaura didn't have time to write all those proposals himself, so I said "Oh well" and started helping him out. I was thinking I might be done with anime since I was already thirty years old, but Mr. Yamaura and the rest of the staff were calling me on the phone every day. (laughs)

Masao Iizuka & Ryosuke Takahashi — Atom's Genes, Gundam's Dream Episode 6

Iizuka: When I came over from Mushi Pro to Soeisha, it was just to format the proposals. I was purely assisting Mr. Yamaura as a side job... But my take-home pay was higher than Mr. Yamaura's. When we were walking together, he'd fumble at my chest. I'd say "Huh?" and he'd say "Cigarette." (laughs)

Speaking of money, he'd say "I can't afford the teahouse for our meeting, I'll pay you back when my advance payment clears." It would often end up with me gathering receipts from Mr. Yamaura's pockets, writing up invoices, and having him send them to Tohokushinsha for reimbursement.

Takahashi: He was bumming cigarettes off you! (laughs)

Iizuka: The people in Kami-Igusa's shopping district thought we were brothers. "Your big brother always seems so busy," they'd say.

Yoshie Kawahara, an early Sunrise staffer who was assigned to the planning office in 1980, has written extensively about her experiences at the company in "Coelacanth Kazama's True Stories," a long-running feature series for "Great Mechanics" magazine. Here's how she describes the work of the planning office, and her supervisor Iizuka's role in it.

Yoshie Kawahara — Great Mechanics G, 2022 Winter

The planning office had also served as "Sunrise's do-anything division," partially responsible for publicity and for matters which would be handled by the general affairs or legal departments in a normal company.

This was because our desk chief Mr. Iizuka, who had been recruited by Sunrise from Mushi Production's reference department, had historically taken on sole responsibility for organizing and storing everything from planning-related documents to intermediate products from the production site—in other words, scripts and storyboards, setting materials, and even key frames and used cels.

Up until the mid-1980s, the plans themselves took the form of proposals the planning department manager Mr. Yamaura put together with scriptwriters, directors, and designers he deemed suitable for the project's objectives. These were then presented to sponsors and advertising agencies.

Mr. Iizuka served as Mr. Yamaura's right-hand man. But as I've mentioned, various jobs were being done at the same time, so crowded planning meetings and so forth were rarely held in the "planning office" itself during so-called business hours, but took place in neighborhood coffee shops and other separate locations. As a result, the people on site often thought of Mr. Iizuka as nothing more than "Uncle Cel-Organizer." But he laughed it off, saying "That's fine, it's true after all."

As the company grew, and the volume of material to be archived increased, the planning office would be repeatedly relocated.

Yoshie Kawahara — Great Mechanics G, 2022 Winter

As far as I know, up until about 1976, the original "planning office" was a single Japanese-style room split in two, on the fifth floor of the narrow building that housed the coffee shop "Sansan" where meetings were often held. After that, it moved to an apartment in the back of the building that contained the original head office. That was a Japanese-style double room.

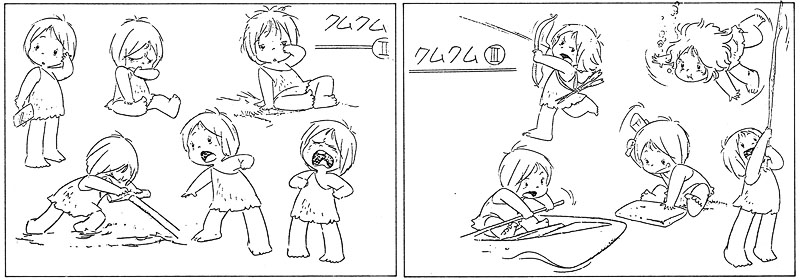

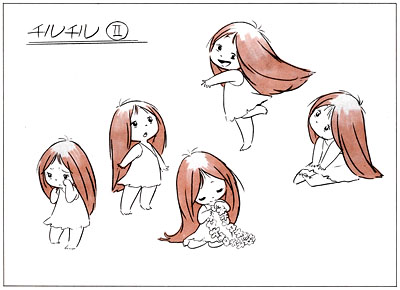

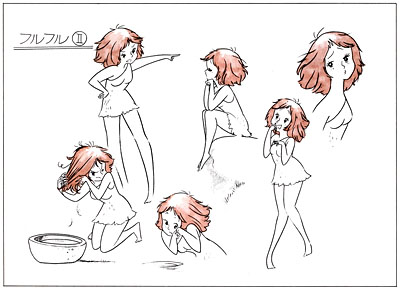

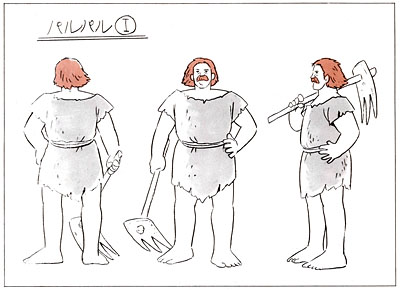

From 1978 onward it was in an old single-floor space about 20 tatami mats in area, previously known as "Studio 3," which had been used as a production site ever since Kum Kum (1975). That was on the second floor of a grocery in front of the train station. Around 1983, it moved to the third floor of the old head office building... little by little, it was expanding.