Production Reference:

Production Reference:Translator's Note: Gundam-Mono: The Men Who Made Gundam, published by Kodansha in October 2002, is a collection of long interviews with major staff members involved in the creation of the original Mobile Suit Gundam. The interview with Masao Iizuka, formerly of the Sunrise planning office, is particularly interesting and I've translated the bulk of it here.

Translator's Note: This interview runs to a total of 36 pages, including a brief introduction. In the following translation, I've omitted this introduction and the final two sections that cover the planning and development of Mobile Suit Gundam.

|

|

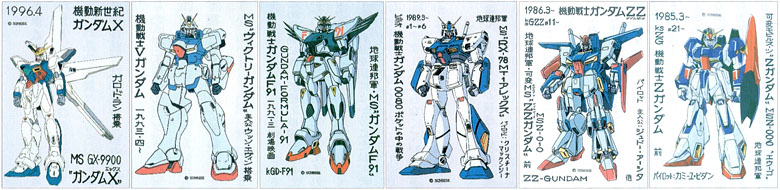

Born in Tokyo in 1941. Joined Mushi Production 1963 and was assigned to the reference room, which was "in a warehouse-like state" at the time. Here he was responsible for organizing and storing animation materials, and managing the repurposed cels used in the so-called "bank system," in which the same drawings were reused over again. After Mushi Production went bankrupt, he joined Soeisha, the predecessor to Sunrise. Working in the planning office alongside (then) planning chief Eiji Yamaura, one of the founding members, he was involved in the planning of Sunrise's works. He played a major role in both the drafting of plans and the actual production process for works such as Super Machine Zambot 3 (1977), The Unchallengeable Daitarn 3 (1978), and Mobile Suit Gundam (1979). Later, as the head of the Sunrise reference room, he was responsible for the management of repurposed cels and the systematic organization and storage of all materials required for animation production, including setting materials for mecha, characters, and accessories, and even scripts and storyboards. As well as supporting the production site, he also negotiated with the published media, and became known as Sunrise's wise counselor. Moreover, in the model sheets from Sunrise anime works featured in various books and publications, the distinctively precise lettering used to write the names, performance, dimensions, and so forth was Mr. Iizuka's own handwriting. |

A selection of model sheets from the Gundam series showcasing Iizuka's distinctive handwritten lettering.

In addition to director (Yoshiyuki) Tomino, the Gundam staff included Mr. Yasuhiko, Mr. (Mitsuki) Nakamura, and Mr. (Kunio) Okawara, as well as the scriptwriters Mr. (Hiroyuki) Hoshiyama, Mr. (Yoshihisa) Araki, Mr. (Yuu) Yamamoto, and Mr. (Kenichi) Matsuzaki who we brought in to make the science fiction setting as authentic as possible. All of these people participated under a project contract, and everything else was outsourced. (1) Back then, Sunrise wasn't as big as it is now, and the managers were the only employees. It wasn't just tiny, it was microscopic. (laughs)

Sunrise was originally created by middle management people from Mushi Pro, seeking to go independent now that it was too late to turn their former company around. The people who created Sunrise, as well as those who left for other companies, had been trying desperately up until then to rebuild Mushi Pro. But there was nothing more they could do.

Even if they wanted to be independent, though, they didn't have any money back then. Their salaries were pretty low. (laughs) So they approached President (Banjiro) Uemura of Tohoko Shinsha, which had been responsible for the sound in Mushi Pro's works, and started up as a subsidiary of Tohokushinsha. Soeisha was the planning and production division, while Sunrise Studio was the division that created the actual animation at the production site. (2)

I joined Mushi Pro in August of 1963. But when I started, I thought "This isn't a real company." (laughs) It had the atmosphere of a college club. Tezuka-sensei and the other founding members—Mr. Yusaku Sakamoto, Mr. Eiichi Yamamoto, Mr. Gisaburo Sugii, Mr. Rintaro, and everyone else—were all working without enough sleep. (3) When they were in charge of a work, they couldn't go home for a month. (laughs)

At the time I was delighted to be assigned to the reference room, which was full of Tezuka-sensei's manga and reference books, and I felt pretty optimistic. But when I actually got there, the situation was terrible. (laughs) Let me express in numbers the ridiculousness of what Mushi Pro was doing.

In a Disney movie, thirty minutes of animation would require more than 40,000 cels. (4) But given Mushi Pro's time and budget constraints, they had to somehow keep it down to about 1,500. 40,000 versus 1,500! With 1,500 frames, you couldn't make an anime if you did it the same way. So Tezuka-sensei came up with some techniques that he'd also been using in manga, such as making a single drawing appear to move via camerawork, or moving only the eyes and mouth while the face stayed still. In other words, what's called limited animation.

It seems that at first Mr. Sugii, Mr. Rintaro, and the other animators were really confused. For example, even if only the mouth is moving, Japanese still has five vowel sounds. And there's also the closed mouth, so you'd actually need to draw six different patterns. But they cut that down to just three frames—a closed mouth, a wide open mouth, and one in between. As for eye blinks, in extreme cases they'd just have two versions, open and closed, with no transition. Nonetheless, the frame-dropping visual effect this created actually felt right for a speedy work like Atom. In a Disney movie, the movement is somehow viscous, isn't it? (5) That's because they started out using a method where they'd shoot live action, and then draw the characters by tracing over the film.

Led by Tezuka-sensei, who was in his thirties, the staff who ranged from their teens to their thirties were all working their hardest. We were all so young then...

In addition to reducing the number of frames, another method Mr. Tezuka came up with was to reuse and repurpose drawings. If Atom is always Atom, and Doctor Ochanomizu is always Doctor Ochanomizu, he decided we could use the same drawings for similar scenes. It was the reference room, where I was working, that managed those drawings. This came to be known as the "bank system," but that name never felt right to me. They called it a bank, but it wasn't a institution that earned money by making loans. It was really a library system, because people would borrow things and then bring them back. That's why the repurposing field on the old cut bags is still labeled as "lib," because I rewrote it. (laughs)

He came up with a lot of ideas, but the animators and everyone else thought about it as well. At first, the animators were responsible for episode direction as well. By the time I joined, the production process was gradually taking shape. First, the original manga was turned into a storyboard and checked by Tezuka-sensei. Unlike today, the people doing the key art were divided into first and second key animators, with the first key animators drawing the layouts and instructions, and the second key animators drawing the actual performance. (6) Then the animation staff would do the in-betweening and clean up the key frames. (7)

As the broadcast continued, however, we eventually used up all of Tezuka-sensei's original work, and the decision was made to start transposing his other short manga into the world of Atom. So we now needed professional scriptwriters and episode directors.

To go back to the start of Atom's production, pioneers are really amazing. When people are in a jam, they come up with ideas. At the time, Toei Doga said it was impossible to broadcast an episode of Atom every week. They figured it took about three years to create a single theatrical anime, so naturally they didn't think you could do a thirty-minute anime with 1,500 frames. But Tezuka-sensei didn't give up. He didn't have time to direct it all himself, so he shared the episode direction and key animation work with Mr. Sakamoto and the others. The system of having roughly five teams, working on an episode each and staggered one week apart, was also born during the production of Atom.

I gather that, at first, they were only earning about one-third of their production costs. (8) Tezuka-sensei would say "I can make up the difference with the income from my manga, so don't worry about that and just keep working as hard as you can." It seems he just increased the number of manga serials he was doing, sacrificing his sleep to keep up.

Mr. Tomino started in the spring of 1964, the year after Atom began. It was a time when we were recruiting a lot of people because we were short of manpower. Once they brought in more people, we could all finally catch our breath. Mr. Yasuhiko joined us much later.

In the process, as Atom's reputation grew and the revenue from character merchandising increased, we found we could somehow manage even if we kept adding people. After about a year, even a youngster might be assigned to direct episodes if they had some ability. One after another, new characters like Uran and Cobalt appeared in Atom, and it became really popular.

In the autumn of 1963, Toe Animation started doing Wolf Boy Ken, and TCJ, the predecessor to today's Eiken, began producing 8 Man. Now the audience was split three ways, and so were the merchandising opportunities, so a competition had begun. There were already three companies, then others like Mr. Tatsuo Yoshida's Tatsunoko Production also joined in, and soon there were several anime programs being broadcast every week.

Then anime entered the color era with Jungle Emperor (1965). Back then, you needed about a year for preparation, and because the performance of the cameras and TV sets wasn't very good, the colors they produced were terrible. Fuji TV's engineers, and Mushi Pro's managers and color designers, were focused intently on that. The number of colors was limited, too. Now you could probably use tens of thousands. Thus the sixties became the era in which TV animation was born and developed.

Mushi Pro expanded until it was producing five works at the same time, and had more than four hundred employees. Its headcount had now reached a point where it could be called a major company, not just a midsize one. Ultimately, though, its organizational capability and financial strength remained just as weak as when it was originally founded. It was in a situation where it was constantly receiving advance payments for its next works and using the money to fund the production and broadcast of the current ones.

In the course of this animation history, Mushi Pro's condition gradually worsened. Now there were so many works competing with each other, its supplemental income from character merchandising fell, and on the content front there was the problem that not all of Tezuka-sensei's works could be turned into TV anime. With all these various problems piling up, by the beginning of the seventies the company's bankruptcy was inevitable.

By that point, Toei Doga, Mushi Pro, and Tatsunoko Production had all become large organizations. But working conditions were poor everywhere. That's why they formed labor unions, and why the labor movement was so vigorous from the mid-fifties to the end of the sixties. (9) In that kind of situation, the work would fall behind due to labor disputes. A lot of animators are the kind of people who just want to draw pictures and get on with their work, so one after another, they started going independent and establishing subcontracting companies.

This development made it possible to establish a business like Sunrise, which didn't have an actual production work department, but was able to plan, produce, and sell animation while subcontracting the production work itself. (10) That was pioneered by Tokyo Movie Shinsha. Before that, the company itself had to take on all the staff required to make things.

First, they spent half a year working on Hazedon (1972), a manga-based show that was ordered by Tohokushinsha. After that, they decided to start doing original stories. At the time, Tohokushinsha was importing TV programs from overseas and securing the Japanese merchandising rights. One of these, Thunderbirds (1965), had become a huge hit. The program was well received, and the merchandise was selling well, too. So President Uemura of Tohokushinsha and Soeisha told Mr. Eiji Yamaura, the person in charge of planning, "You should make a work like Thunderbirds."

The result was 0-Tester (1973). It was made with the help of Mr. Yoshitake Suzuki and other scriptwriters who were still at Mushi Pro, as well as the predecessor of Studio Nue, a group of students who were in an SF research club. As for me, at that point I was still finishing up remaining business at Mushi Pro. The audience ratings weren't bad, and the merchandise sold well. When the merchandising is successful, the sponsors will continue supporting you and the program's broadcast will be extended, and thanks to this it ran for about a year and three months.

Really, it all started with Mighty Atom. Until then, pretty much all you had were the Disney characters and Fujiya's Peko-chan. (11) Then, with Atom, a manga character became recognized throughout Japan through the powerful medium of television. Based on that, a business model was established which extended into a variety of merchandise. But at the time of Atom, this merchandising mainly consisted of printed media. Rather than merchandise of the characters themselves, they were products with the characters printed on them. The main sponsor, Meiji Seika, was just releasing caramels and chocolates with Atom on the packaging, but they sold like hotcakes. The results were so good that they eventually overtook Morinaga & Company as the industry leader. And in terms of animation, back then Japanese TV stations would buy and broadcast Disney short films, but Atom was the first time they ever did that with a domestic production. So Atom was a revolutionary work in terms of both TV programming and character merchandising.

Until Tezuka-sensei came along, there were virtually no characters who'd been creatively formed to the point where they could be independently merchandised. Even the majority of manga characters were just caricatured drawings of human beings. In that sense, Mr. Suiho Tagawa's Norakuro (1931), in which human society is populated with anthropomorphized dogs—or idolized, as we'd say today—was groundbreaking in the history of Japanese characters.

This is also hearsay, but in the days before Mushi Pro, he once went to the bathroom and didn't come back for a while. When his editor forced the door open, it turned out he'd climbed out the window in his bare feet and escaped down the drainpipe. (laughs) But it's no wonder. In terms of manga alone, he was doing up to nine weekly serials, as well as one-shot stories. And he was doing anime work on top of that. No ordinary human being could have done that. He worked without sleeping, and I think it's really sad that might be why he died so young.

Anyway, he was a person with a real service mentality, who just wanted to show these things to children. He didn't have any thought for himself, or for the profits of his organization. I gather that at the beginning, he was even drawing the key art for Atom himself. I think he was truly superhuman.

That's right. Now they had toymakers as sponsors. Then a work appeared in 1972 that marked a revolution not only in the quality of the work, but in the business model of the animation industry itself. This was Toei Doga's Mazinger Z (1972). It's no exaggeration to call this work an anime produced with a complete focus on toys as the main form of merchandising, and it was hugely successful. Or at least that's what Toei Doga intended, but perhaps the original creator Mr. Go Nagai had other ideas.

One factor was that societal conditions had developed to the point where products like that could appear. Previous character toys had generally been tin toys, and the technology to turn them into higher-quality products didn't yet exist. When these were released in the form of heavyweight figures like the Mazinger Z Chogokin, they were a real hit. These were actually cast from ordinary zinc alloy, but their weight perfectly matched a child's image of a robot. This, too, was due to societal conditions, as these products were realized because the diecasting technologies of the metallurgical industry could now be adopted by the toy industry as well.

They ended up being happy that 0-Tester was well received. But then they had to write a new proposal every week as they wondered what to do next. At that point I heard Mr. Yamaura didn't have time to write all those proposals himself, so I said "Oh well" and started helping him out. (12) I was thinking I might be done with anime since I was already thirty years old, but Mr. Yamaura and the rest of the staff were calling me on the phone every day. (laughs)

Then, as we were fretting about what to do next, President Uemura of Tohokushinsha gave Mr. Yamaura the instruction that "Toei Doga is making a lot of money doing Mazinger Z, so you should make a big robot." (laughs) Mr. Yamaura came back and asked me "Iizuka-chan, he told us to make a big robot. What should we do?" We'd never done a giant robot show, so of course we didn't have a clue. We all just groaned and held our heads.

That's right. Mr. Yamaura tried conferring with the members of Studio Nue, watching the Mazinger Z series and Getter Robo (1974), and reading manga, but he still couldn't figure out why giant robot shows were so popular. So I started going to the toy sections of department stores and talking directly with the children there. Nowadays we'd call that market research. I interviewed the kids as we played with the toys, and realized that they were attracted to giant robots because there were certain desires they fulfilled.

Though these were called giant robot shows, they said "The hero is a normal human, so they can't beat the enemy monsters and evil robots on their own. But they can become bigger and stronger by getting into a robot. That's the good part." The backdrop to this, I thought, was the nature of the families the children belonged to, the smallest unit of society. They had fathers and mothers who were much bigger than they were, as well as older brothers and sisters, so they couldn't really behave the way they wanted. At such times, it was appealing to think "If only I could get into a robot like that..."

It was a kind of wish for metamorphosis. If only I could become bigger, they said. The first work that fulfilled that wish was probably Ultraman (1966). But according to the science-fictional setting, he could only become bigger because he was an alien. In Mazinger Z, which began the shift to giant robot anime, I felt the empathic connection was stronger because it was a human protagonist boarding the robot. If you had a robot like that, then you could be big and strong, too. From this idea alone, I think you can see how amazing Mr. Go Nagai is.

Based on these interviews, we decided to make a work in which the robot's control method—or, as children of the time would say, the way you drive it—further evolved from "getting into the robot" to "the hero becomes one with the robot."

But we were purely fumbling around at the time. We started with this idea of becoming one with the robot, and then came the concrete image. Robot designs at the time were crude and powerful, and if anything, I'd say they mainly had villainous faces. When I asked children about this, they said they'd be happier with a design that conveyed a clearer sense it was an ally of justice. (13) So that's what we went with, and rather than a massive lump of iron, we tried to give the robot a more streamlined form and a sharper image. Thus we arrived at the image of Reideen the Brave (1975).

That's how we arrived at the concrete design. It was something you could easily empathize with, because it fulfilled your own desires on your behalf, so we thought it would be better if the design was very humanoid. Then we considered what its appearance should be based on. Mazinger Z and other robots of the time were based on armored Western knights. Since we were Japanese, we decided to go with Japanese samurai armor instead. Naturally, that was also influenced by the fact that our generation had watched a lot of Toei samurai swordfighting movies. (15) (laughs) The original concept for the Reideen's head was actually inspired by the image of an eboshi cap.

Likewise, they'd previously been using relatively harsh colors like black and red, but I asked the children what colors they liked and what they thought would be cool. Ultimately we went with red, blue, and white tricolors. Using these as a base, we decided to add golden decorations, since even kids love gold. In the animation, however, the gold ended up being represented as yellow. Those would henceforth become the basic colors of Sunrise robots.

Next we had to create the worldview of the story. At that point Mr. Yamaura commented "It seems like the Seven Wonders of the World are pretty popular these days, but what the heck are they?" Back in the mid-seventies, there was a real craze for occult things like pyramid power. I explained "The Seven Wonders change from one era to the next, but right now, there's a lot of stuff being published in magazines about pyramids, Atlantis, and the lost continent of Mu." He replied "That's it!" So we decided to go with that kind of mystical worldview. This was also reflected in the design of the robot, as the Reideen became a fusion of an armored Japanese warrior and the mask of Egypt's Tutankhamen.

The reason is that, back then, we weren't even in second place. They were about to begin airing the third work in the Mazinger Z series, UFO Robo Grendizer (1975), so if we did our own giant robot now we could only hope for third or fourth place. (16) In that situation, the only way we could compete was to send something new out into the world.

But even if we said it was something new, it would still be a work featuring a giant humanoid machine, so whatever we did there wouldn't be much variety. In order to differentiate ourselves, first we had to properly analyze the giant robot show genre. And we needed to understand the preferences of the children, too. But how well we'd actually be able to achieve that was a different matter.

We even tried to come up with a different way of getting into the robot. In Mazinger Z, the pilot first boards a small craft called a Pilder, and this Pilder then fits into the robot's head. It seemed like that would be dangerous if the robot were hit in the head. (laughs) We were wondering what to do, and then we remembered a manga by Tezuka-sensei called Majin Garon (1960), where there's a child named Pippy-chan inside the robot's chest. (17) We decided to go with that. In a child's imagination, the most important part of the body isn't the head, it's the heart.

Since it's a robot from the mysterious continent of Mu, the pilot gets in by being absorbed into the robot with a burst of light, and ends up in the neighborhood of its heart. From a logical standpoint it's nonsense, but we figured "It's okay because it's the 'King of Mystery.'" (18) (laughs) Borrowing a cinema term, we gave it the name "Fade In."

Of course they were. Anyway, we tried to include as many ideas as possible that would please children. The protagonists' daily life takes place in an ordinary school, so the work includes elements of a school story as well as a robot show. You never know which will catch on.

Since Reideen was an original work, kids wouldn't have heard the name until it was on the air. So we had the robot shout out its own name to help them learn it more quickly, and that's why we gave it a mouth. (laughs) Maybe we were also trying to make use of the handsome Tutankhamen face by not hiding its mouth behind a mask.

As for weapons, Mazinger Z featured a splendid idea called the rocket punch, but taking the pose, launching the first, and then hitting the enemy required multiple cuts. That made it hard for little kids to understand how the scenes connected together. So with Reideen, we wanted to somehow keep the fighting within a single screen. In other words, short-range close combat. Even in Ultraman, while the enemy are ultimately finished off by the Spacium Beam, up until then it's all hand-to-hand grappling, like pro wrestlers. That's the sort of thing kids like.

Still, it would be underwhelming to defeat enemies with grappling even though you have a robotic machine. We tried to think of a way it could defeat the enemy with some kind of mechanical fighting technique, and the idea we came up with was swordfighting. (19) "Mr. Yamaura, if the Reideen is a Japanese warrior, it should use swordplay." "You're right. That's it!" We decided it should fight with a sword. And once we had swords, we gave it a bow and arrow as well.

The problem was, where on the robot should these weapons be mounted? If it wore a sword at its waist and carried a bow and arrow on its back, it wouldn't really seem like a new kind of robot. So we built the bow into the left hand, and had it pop open to nock the arrow. If it had weapons, it also needed some defense, so we put a small shield on its arm which gets bigger when in use. The sword also comes out of there. It's all ridiculous, but once again, we dismissed that by saying it was fine because it was the "King of Mystery." (laughs)

There was one more important setting element that appeared for the first time in the history of giant robot shows, namely transformation. The Reideen transforms into an aircraft form called the "God Bird," but rather than coming from us, that idea was suggested by the sponsor Bandai. They actually built a model and demonstrated it during a meeting. If you lay it down like this and raise the legs, they said, it suddenly becomes an aircraft. Mr. Yamaura and I thought the toymakers were really impressive, and it was truly a revelation.

Up until then, giant robots had never transformed or combined. Well, they did combine in Getter Robo (1974), but there they combined by warping the metal itself, and it wasn't something you could mechanically reproduce. After Reideen, they started making giant robot toys that could transform and combine.

No, it was terrible. Even if you try things, you have no idea if they'll be well-received. (laughs) There was a lot of anxiety, but one thing after another came up that I had to deal with, so I couldn't dwell on my worries and just had to get through them.

Mr. Yamaura and I were always just fumbling around, wondering what the heck we should do. But it was really crucial that we had "brains" to help us make our ideas concrete, and people with abilities and sensitivities that meshed with that. Not only during Reideen, but afterwards as well, Mr. Yamaura was constantly doing his utmost to get these kinds of talented people involved in Sunrise's works. As well as Mr. Yoshiyuki Tomino, that included Mr. Yoshitake Suzuki and other scriptwriters, Mr. Yoshikazu Yasuhiko, the members of Studio Nue, and Mr. Kunio Okawara—although Mr. Okawara's participation began after Reideen. When someone does something with all their might and enthusiasm, the people around them will be drawn in as well.

Reideen had setting elements such as a mystical worldview and complex personal relationships which weren't found in previous giant robot shows. That made it more interesting on the creators' side. But since we were all middle-aged guys in our thirties, if we just made it the way we found most interesting, it would be difficult for the kids who were our main audience to understand. And then we'd be deviating from our objective of getting them to buy robot toys and picture books.

Middle- and high-school fans were delighted, and they started sending us fan letters and coming to hang out at the Sunrise studio, but the hard reality was that we'd go out of business if we couldn't get the ratings. That hit us like a sudden blow to the head. So after that, Sunrise struggled through a lot of trial and error. We made a show called Robokko Beeton (1976) aimed purely at children, which was like a cross between Obake no Q-Tarō and Doraemon.

Ultimately, due to the opinions of the broadcasting station and the advertising agency, the decision was made to replace the producer and director in mid-series. The content also underwent various changes. It turned out that kids only wanted to watch scenes of the robot in action. So we'd show them a battle even in the first half of the program, with Reideen at a disadvantage. Then we'd construct each episode so that it turns the tables and settles things in the second half. Since that alone would get repetitive, we also created setting where the combat scene in the first half would be a battle among the enemy side to determine who'd get to challenge Reideen that week, and then the winner would fight Reideen.

Even with an original work, the story's starting point and an outline of its eventual conclusion are roughly envisaged at the beginning, during the planning stage. But just as the content of serialized manga can change based on surveys and so forth to match the trends of reader desires, TV animation often has to be shored up after it's already on the air, because it's too far ahead of or behind the times, or it doesn't match the trends among viewers and sponsors. The result was that the first half of Reideen was popular with middle- and high-schoolers, while the latter half was poorly received by them but popular with little kids.

That's right. At Sunrise, the robots come first. (laughs) It all starts with creating a toy—that is, a robot—that the main sponsor can make money selling.

Exactly. That kind of process isn't necessary when it's based on a preexisting original work, but the drawback is that then you have to pay royalties to the original creator. (20) With our own originals, all of that becomes income for the company, which is appealing in business terms. But unlike with a preexisting work, there's a definite risk that it won't be accepted in the marketplace. No matter what, the tastes of the creator will always come to the forefront, and there's a possibility they may not be aligned with the trends and demands of the public.

While Reideen struggled in the first half, it also managed to earn a certain degree of appreciation. But at the time, Soeisha was a subsidiary of Tohokushinsha. In that situation, even if the work was successful, none of the profits would flow directly to its production division, Sunrise Studio. With glum faces, Mr. Yamaura and the other managers would grumble that "We're not making any money, and our salaries aren't going up." But by that point, we'd been able to make some tentative connections. And when the chance finally came, we decided to take the plunge and go independent. The company we created was Nippon Sunrise (1977~).

Fortunately, at the time, we'd been entrusted with the production of Super Electromagnetic Robo Com-Battler V (1976), a work planned by Toei. Well, I say it was planned by Toei, but while the design of the main robot was already completed, Sunrise was responsible for the task of cleaning it up so it was suitable for animation, as well as the character design. Incidentally, in those days that sort of work was mainly entrusted to Mr. Yasuhiko. It got to the point where we were told "Don't rely on Mr. Yasuhiko for everything." (laughs)

We also incorporated a lot of other setting to make the work popular, and as a result, it became a hit and sold a lot of merchandise as well. Based on these results, even though the raw material came from Toei, the efforts of the Sunrise staff who had interpreted it came to be recognized within the industry. After Com-Battler V, Sunrise was entrusted with the production of a series consisting of Super Electromagnetic Machine Voltes V (1977), Fighting General Daimos (1978), and Future Robot Daltanious (1979).

Since Sunrise had gained this much capability we figured, well, maybe we can manage this on our own. (laughs) Clover, which had previously been a vendor of soft vinyl toys, agreed to sponsor us. The first work we produced like this was Super Machine Zambot 3 (1977). None of the big advertising agencies would work with us, but we finally found the Tōyō Agency, which is now Sotsu. The broadcaster was the local station Nagoya TV. These were all minor players, or at least not major ones. But I now think that was a blessing.

The production of Zambot 3 began, with Mr. Yoshiyuki Tomino returning as series director. Though it was called tragic, dark, and brutal, it was also praised for its interesting setting and dramatic story. Based on this, in the following Unchallengeable Daitarn 3 (1978) we aimed for an exciting action drama without a trace of logic. Since the main robot in the previous work had combined, this time we tried to differentiate it by changing the mechanism to a transformation. Mr. Okawara's design was also very good, and the merchandised toys were well-made and sold nicely.

This was very profitable for Clover, and they decided to build a new company headquarters. "But if we keep going on like this," we said, "we'll always be just scraping by, six months or a year at a time." (laughs) The only way we could escape that cycle was to create a work that would make the Sunrise name itself a household word, rather than just a program to sell robot merchandise. To do that, we thought we had to make something like a long-running taiga drama, which would leave a strong impression on everyone. (21) At the time, there was already a precedent for this in the form of Space Battleship Yamato (1974). But we also knew that a plan like that would never be approved.

One day, Mr. Yamaura returned from a meeting and said "Iizuka-chan, that thing... They said we can do that thing!" That's how Gundam began. Of course, at that point we didn't yet have a definite image, but the sponsor approved the prototype plan thanks to the merchandising track record we'd established with Zambot 3 and Daitarn 3.

One of the goals of the Gundam plan was to develop the market whose existence had been demonstrated by Yamato. At the time, animation was watched mainly by elementary school students—particularly the lower and middle grades, as they gradually drifted away when they entered the upper ones. (22) By the time they were in middle school, they'd pretty much stopped watching. The core fans of Yamato, on the other hand, were in middle school or above. We wanted to make a work like that, too. That meant we had to break away from the traditional format of giant robot anime, a structure in which a new enemy shows up every week and gets defeated, and the story only differs in the first and last episodes. That's what Yamato did, after all.

We had the staff for it. And we wanted that staff, who had worked with Sunrise since it was first founded and helped make it into an independent company, to be recognized as talents whose abilities put them in the top tier of the anime industry. First, as series director, we had Mr. Yoshiyuki Tomino. Despite his talent, skill, knowledge, and ambition, he'd never been blessed with the right timing and the right work to fully demonstrate what he was capable of. But this was a work which couldn't have existed without Mr. Tomino.

Then came the chief writer, who would create the overall worldview and character depictions together with the director. Ever since Reideen, that had been the responsibility of Mr. Yoshitake Suzuki, but he wasn't available to work on Gundam. So the person we singled out for this was Mr. Hiroyuki Hoshiyama, who had previously been writing scripts for us. The other writers were Mr. Yoshihisa Araki, who we could always rely on for polished scripts; Mr. Yuu Yamamoto, who depicted distinctive characters; and Mr. Kenichi Matsuzaki of Studio Nue, whose career as a writer was still in its early days but who knew a lot about SF research. These five people created the story in their meetings.

With previous works, we could place orders with each writer individually, and throw the result in anywhere. But since Gundam was a taiga-style serial drama, we needed to have everyone get together and think about it, with Director Tomino in the middle coordinating everything. We'd never done this kind of group story creation before.

Of course, no matter what, we wanted Mr. Yoshikazu Yasuhiko as animation director. Mr. Yasuhiko had shown his talent in Sunrise's first giant robot work, Reideen, where did the character design and revised the mecha for anime use, so he was someone who'd laid the foundation for all Sunrise robot works. For this plan, we wanted him to demonstrate his ability to draw the trendiest characters of their time. Because we had him design the characters, Gundam gained many female fans as well as male ones, and it became a work that people watched for the charm of Mr. Yasuhiko's characters. This was a major reason for the initial enthusiasm of Gundam's fans. Meanwhile, from the very beginning of the story, fans of SF and mecha were also attracted by the visual expression of Tomino-style directing.

The problem, though, was that Mr. Yasuhiko was still working on Yamato at the time. We asked him anyway, and though he couldn't leave Yamato until December 1978, we managed to have him come and join us in January 1979. Ultimately, however, his Yamato work dragged on until March. That made things really difficult, since the broadcast of Gundam began in April.

Mr. Kunio Okawara continued on from Daitarn 3 as the mechanical designer. He also provided the three-dimensional drawings of the robots that the toymakers normally had to do, including three- and six-sided views. The designs Mr. Okawara draws can be reproduced in three dimensions with no changes, and he can make even transformation and combination mechanisms intuitively understandable. We also had him try doing illustrations, using the anime pose collections drawn by Mr. Yasuhiko as reference. When the movies were being made, he did posters and so forth, drawing everything from rough drafts and source images to the final painted color illustrations. Mr. Okawara is very skilled, and he really enjoys this kind of work.

This is a digression, but Mr. Tomino was pretty jealous of this pair's talents. (laughs) Mr. Tomino is a clever person with a keen thirst for knowledge. In the last days of Mushi Pro, he was creating his own stories as he directed episodes. And he was so fast at drawing storyboards! For a while, they called him "the cutter of a thousand storyboards." (23) He'd also do rough drawings to convey his own image of character and mecha designs, but he couldn't do it that well because he wasn't an artist. So he'd exclaim "Damn that Yasuhiko! Damn that Okawara!" (laughs) He was always lamenting "If only I had a talent for drawing." But even among the other animators, there must have been plenty of people who secretly felt that way, because those two had aspects of genius. People like that can draw anything in one go. And people like Tezuka-sensei were truly amazing.

Translator's Note: Iizuka continues on to discuss the planning and development of Mobile Suit Gundam. Much of this account duplicates the one he gives in the 1998 book Gundam Age, so I'll stop here for now.

(1) The term 作品契約 (sakuhin keiyaku) refers to a short-term contract for the duration of a particular series. Normally I'd translate 作品 as "work," as in a creative work, but that would be confusing in this context.

(2) The division of labor described here hinges on the distinction between 制作 (seisaku) and 製作 (seisaku). Though they're pronounced the same in Japanese, and both are usually translated as "production," the former refers to managing the work process and the latter refers to the physical creation of the work. At this point, these tasks were handled by Soeisha and Sunrise Studio respectively.

(3) I was originally inclined to gloss "Tezuka-sensei" as "Master Tezuka," but the nuance doesn't feel quite right.

(4) At 24 frames per second, the exact figure would be 43,200 cels.

(5) I suppose one might describe Disney animation as "fluid," but the term ねばっこい (nebakkoi) seems less flattering, with a meaning closer to "sticky" or "gooey."

(6) The term 原画 (genga) refers to the drawing of rough key frames, so it's technically not actual animation. In later productions, the "genga-men" would also draw layouts and plan the timing of the animation, but based on Iizuka's account these tasks were separated in the Mushi Pro system. This is also discussed in the first part of Matteo Watz's epic history of Mushi Pro.

(7) The term 動画 (dōga), sometimes interpreted as just "in-betweening," literally translates to "animation" and encompasses both in-betweening and cleanup of the key frames.

(8) As explained in Matteo Watz's Mushi Pro history, this rate was increased as the series continued.

(9) Literally, from the 30s to the mid-40s in the Showa calendar.

(10) Once again, Iizuka's description hinges on the distinction between 制作 (seisaku) and 製作 (seisaku). At Sunrise, this second kind of production—the physical creation of actual animation—was largely subcontracted or outsourced.

(11) Fujiya is a chain of restaurants and confectionery stores, known for introducing the Christmas cake to Japan and for its Peko-chan mascot character.

(12) This seems to be the point at which Iizuka officially began working at Sunrise—or Soeisha, as it was then known—and so I've switched the phrasing of my translation from "they" to "we."

(13) The phrase 正義の味方 (seigi no mikata), literally "ally of justice," is a cliched way of describing a heroic champion. For example, the opening theme from Tetsujin 28 tells us that the title robot can be an ally of justice or the pawn of the devil, depending on who holds his remote control box.

(14) The phrase 鉄の城 (hagane no shiro), or "iron fortress," is used to describe the Mazinger Z in the show's opening song.

(15) The Japanese term チャンバラ (chanbara) is a subgenre of live-action historical drama focusing on swordfighting action.

(16) The broadcast of Grendizer began in October 1975, six months after Reideen, so Iizuka's recollection may be a little fuzzy here.

(17) I believe the hero in Garon is named Pikku. Iizuka may be confusing this with another Tezuka manga, 1951's Pippy-chan.

(18) One earlier working title for Reideen the Brave was "King of Mystery Emerander."

(19) Here again, Iizuka is using the term "chanbara" associated with Toei's samurai movies.

(20) There's a slight risk of confusion here, since Iizuka is contrasting a preexisting 原作 (gensaku), or "original work," with a Sunrise-created オリジナル ("original"). While I'm translating these both as "original," the surrounding context hopefully makes the distinction clearer.

(21) Taiga drama (大河ドラマ) is NHK's term for its annual historical drama series, and is commonly used to describe this entire genre of historical epics.

(22) Japanese elementary schools have six grades, so based on Iizuka's characterization, children gradually stopped watching anime after they entered fifth grade—in other words, once they were ten years old.

(23) コンテ千本切り (konte senbon-kiri) is one of Tomino's many nicknames. In anime terminology, the task of turning a script into storyboards is known as "cutting."

Mobile Suit Gundam is copyright © Sotsu • Sunrise. Everything else on this site, and all original text and pictures, are copyright Mark Simmons.