Sunrise History:

Sunrise History:This is the second part of a series documenting the fifty-year history of Sunrise Inc.—the studio that produced the Mobile Suit Gundam series—and introducing some of the people who contributed to it.

Officially dissolved in 2022, when it was incorporated into Bandai Namco Filmworks Inc., Sunrise was originally established in 1972 as a subsidiary of the dubbing studio and film distributor Tohokushinsha. I've discussed its early years in a previous installment titled Soeisha 1972~1976, and our story now continues with the company's rebirth as the independent Nippon Sunrise, Inc.

For its first four years, the anime production company that would later be known as Sunrise took the form of two separate entities under the umbrella of Tohokushinsha. Soeisha Inc. was responsible for planning, sales, and production management, while Sunrise Studio Ltd., based in Tokyo's Kami-Igusa neighborhood, did the actual production work. Operating with a skeleton staff, the future Sunrise relied on freelancers and outsourcing to produce its animated works.

Yoshitake Suzuki — Zambot 3 / Daitarn 3 Chronicle

Back then, Sunrise consisted of about nine people who'd gotten together and formed a company, and it didn't have the structure or appearance of a business. For the time being, they had to take on contract work to keep the studio going.

In the early days, Sunrise was a kind of hodgepodge. Even though they knew they had to do everything themselves, whenever they could find the time, they'd go to a pachinko parlor or go drinking someplace. Before it developed a real business structure, it was a weird and irresponsible space filled with chaotic energy.

I think, though, that this irresponsibility was sometimes helpful. When things are incomplete and unconstrained, you can genuinely vent your energy into the work. But you can't necessarily create a good work when everything is precisely ordered into a system.

The titles that Sunrise produced in this era were either created on behalf of its corporate parent Tohokushinsha, which retained all the rights and licensing fees, or subcontracted by other companies such as Toei. But over the years, this arrangement had become a source of frustration.

Masao Iizuka — Gundam Age

The first thing Soeisha made was an original work called Hazedon. Next, Tohokushinsha gave us a project that was supposed to be a Japanese version of Thunderbirds. A team led by Mr. Yamaura, who was in charge of planning, created 0-Tester. This was well received, and also sold a lot of toys.

At the time, Mazinger Z and Getter Robo, created by Mr. Go Nagai, were experiencing a boom. So after this, we planned a giant robot show called Reideen the Brave. The amount of action in the series increased as it went along, and it managed to achieve commercial success. Meanwhile, Toei also asked us to work on the Com-Battler V series, so we were accumulating a lot of experience.

But while Tohokushinsha had made a profit from 0-Tester, as subcontractors, we weren't seeing any of that money. It was like that with the subsequent robot shows, too.

Masao Iizuka — Gundam-Mono: The Men Who Made Gundam

While Reideen struggled in the first half, it also managed to earn a certain degree of appreciation. But at the time, Soeisha was a subsidiary of Tohokushinsha. In that situation, even if the work was successful, none of the profits would flow directly to its production division, Sunrise Studio. With glum faces, Mr. Yamaura and the other managers would grumble that "We're not making any money, and our salaries aren't going up." But by that point, we'd been able to make some tentative connections. And when the chance finally came, we decided to take the plunge and go independent. The company we created was Nippon Sunrise.

In November 1976, Soeisha and Sunrise Studio merged to become the independent Nippon Sunrise Inc. It appears this took the form of the company's founders leaving Soeisha and transferring to Sunrise Studio, at which point Yoshinori Kishimoto, who had been running the studio operations, became president and CEO of the new business.

From the Zambot 3 Memorial Box, a selection of Nippon Sunrise staff and their family members at a vacation destination in July 1978, just after the end of Zambot 3. "In the front row, from the left, are Yoshinori Kishimoto, Masami Iwasaki, Mikiko Suzuki, Masanori Ito, and Masao Iizuka. On the left of the middle row (excluding one person) are Yoshikazu Tochihira, Yasumasa Fukushima, and Eiji Yamaura. In the back row (at upper right) is Tadahiko Horiguchi, who was then a member of Akabanten."

By this point Sunrise Studio had expanded into three different production sites—Studio 1, Studio 2, and Studio 3—clustered around the south side of the Kami-Igusa train station. Since these studios were notoriously cramped, with no space for conference rooms, the local coffee shops were put to use as substitute meeting locations.

From the Zambot 3 DVD Memorial Box, a map of the area around the Kami-Igusa train station during the early years of Soeisha and Nippon Sunrise (circa 1975 to 1984). In addition to various coffee shops, restaurants, and pachinko parlors favored by the staff, it describes the following former studio locations:

Sunrise was eager to leverage its experience and growing reputation to launch an independently created original work. However, the company had three ongoing series already in production—Dinosaurs Catcher Born Free, Super Electromagnetic Robo Com-Battler V, and Robokko Beeton—and with the completion of Com-Battler V at the end of May 1977, Sunrise was subcontracted to work on the followup series Voltes V. It wasn't until October 1977, almost a year after the birth of Nippon Sunrise, that the relaunched company was finally able to debut its first original work.

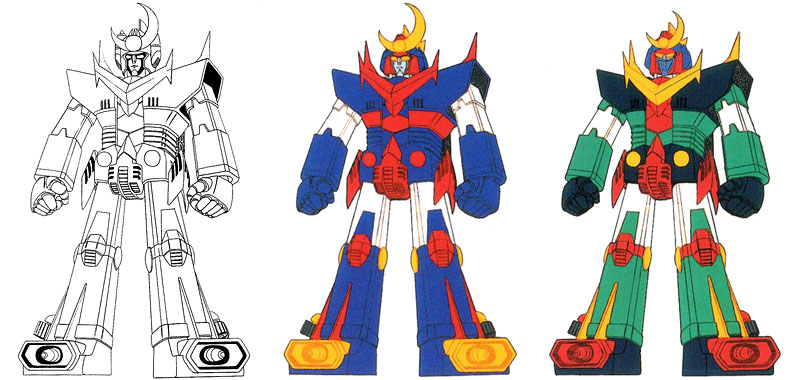

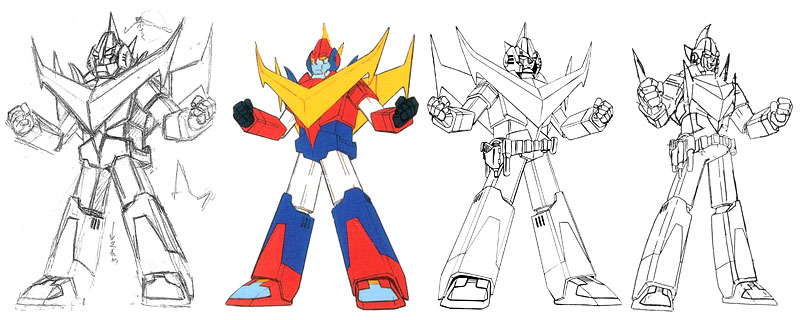

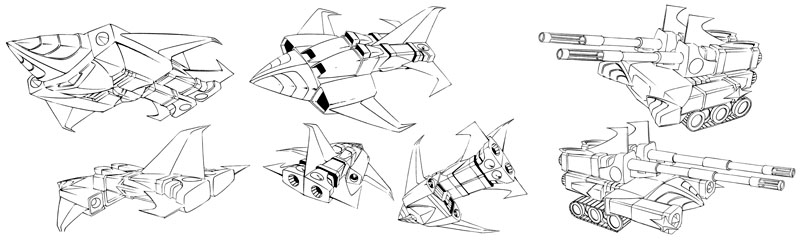

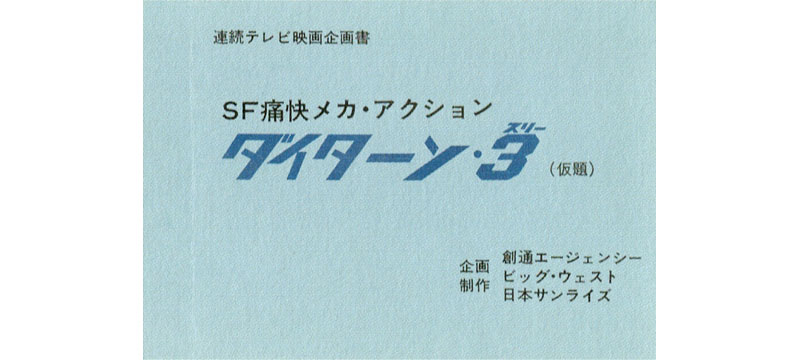

Drawing on the company's expertise with robot shows, the Sunrise planning staff had prepared two proposals in this genre—one which eventually became Super Machine Zambot 3, and another that would later evolve into The Unchallengeable Daitarn 3 but initially bore the working title "Bomber X."

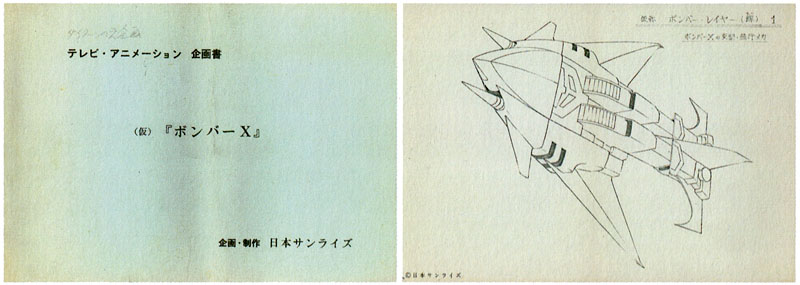

Cover and inside page from "Bomber X" proposal. According to "The World of Tomino Yoshiyuki" exhibition catalog, this dates from "circa 1976."

Though the "Bomber X" plan was actually developed first, it was temporarily derailed by the bankruptcy of its intended sponsor, the toy company Bullmark.

The World of Tomino Yoshiyuki

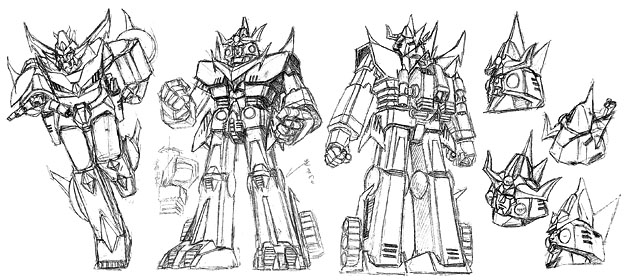

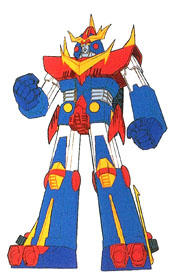

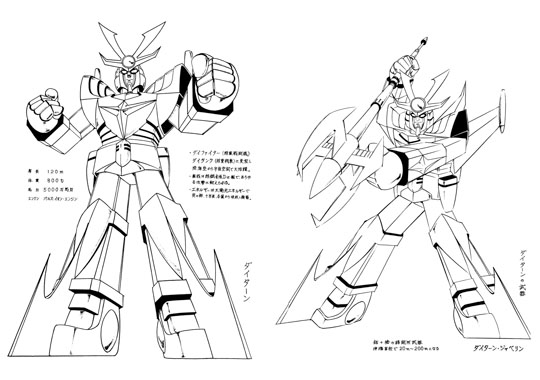

"Bomber X" was Sunrise's phantom first project. Though its content differs from both Super Machine Zambot 3 and The Unchallengeable Daitarn 3, the fact that the protagonist is a boy descended from space aliens who lives on Earth is similar to Zambot 3. The transformation pattern and transformed silhouette of the main robot, the Bomber X, are very similar to the Daitarn 3.

Kunio Okawara — Super Robot Generation Sunrise 1977~1987

The planning of Daitarn 3 actually began before Zambot 3, but the sponsor went bankrupt, so it was temporarily put on hold. It was later decided that Daitarn 3 would be the second Sunrise work.

A sponsor for the other plan was provided through the timely intervention of Kiyomi Numoto, one of Sunrise's original founders, who had since transferred to the toymaker Takara. It was Numoto who introduced Sunrise to Clover, an up-and-coming manufacturer which had previously specialized in soft vinyl toys.

Masao Iizuka — Gundam Age

At just that time, a manufacturer called Clover was looking for its own original program. Back then, Clover was a company that was doing very well selling things like soft vinyl figures, but it was treated poorly by wholesalers because it didn't have much name recognition. So they came to us, saying they wanted an original work. With this, we effectively became independent as Nippon Sunrise.

The Tōyō Agency, a company new to the TV anime business, was recruited to serve as the advertising agency for this new program. Tōyō renamed itself the Sotsu Agency in August 1977, and decades later it would become a Bandai Namco subsidiary.

Masao Iizuka — Gundam Age

We reached out to major and mid-level advertising agencies that handled animation, but none of them would work with us. Somehow, a company called the Tōyō Agency agreed to take on the agency work. But we were anxious because none of us had ever heard of this company. It had never actually offered a TV program, and had started out merely handling the mascot merchandising for the Korakuen Stadium's Giants team. It now changed its articles of incorporation, and its company name as well, and a new company called the Sotsu Agency was born.

The last piece of the puzzle was the selection of a broadcasting station. Nagoya TV, a local affiliate of the TV Asahi network, ultimately became the television home of Sunrise's first original work. This was to be the beginning of another long-running relationship.

Eiji Yamaura — Zambot 3 / Daitarn 3 Chronicle

In short, Nagoya TV, the Sotsu Agency, the toy company Clover, and Sunrise itself were all amateurs who were making anime for the first time. Up until then, Clover had just been releasing low-priced goods for titles where the main products came from major manufacturers. And at the time, 5:30 PM (the broadcast time on Nagoya TV, which was the key station) was a time slot used for reruns. So we hadn't been able to get a good time slot. Even 6:00 PM wasn't really a time slot for first-run broadcasts, but we were able to get by fairly well with a 5:30 PM slot.

The good thing about all of us being amateurs was that normally, if one work becomes a hit, you'd be asked to make a sequel. But they let us make Super Machine Zambot 3, The Unchallengeable Daitarn 3, Mobile Suit Gundam, and The Unchallengeable Trider G7, following harder works with softer ones. Thinking about the viewer's perspective, we figured they'd get bored if we just kept doing the same thing, so we were grateful for that.

After making four shows, however, these amateurs all became professionals. (laughs) And then everyone had their own personal opinions.

The newly independent Nippon Sunrise now launched its own line of original works with a series of giant robot shows, which would enable the company to earn licensing income from toy sales. In the short term, however, Sunrise continued to rely on subcontracting work to support itself. The success of 1976's Com-Battler V had spawned an ongoing series of Toei-commissioned robot shows, and these would command the lion's share of the company's creative resources over the next few years.

超電磁マシーン ボルテスV

超電磁マシーン ボルテスV| TV BROADCAST | |||

| TV Asahi • Saturday 6:00-6:30 PM June 4, 1977 to March 25, 1978 (40 episodes) |

|||

| MAIN CREDITS | Planning | Yuyake Usui (TV Asahi) Takashi Iijima |

Original story | Saburo Yatsude |

| Planning cooperation | Y&K | ||

| Music | Hiroshi Tsutsui | Original character design | Yuki Hijiri |

| Mechanics setting | Mecaman | Animation character design | Nobuyoshi Sasakado Akihiro Kanayama |

| Chief director (総監督) |

Tadao Nagahama | Production cooperation | Tohokushinsha Nippon Sunrise |

| Production | TV Asahi, Toei, Toei Advertising | ||

| ADDITIONAL CREDITS | |||

| Art | Takashi Miyano | Setting assistant | Mitsuko Kase |

| Animation manager (作画制作) |

Tadashi Yahata | Production supervisor (制作担当) |

Masami Iwasaki Yoshihiro Nozaki |

Voltes V, pronounced "Voltes Five," was the second in the "Nagahama Romantic Robo series" following Com-Battler V. Since it began airing in June 1977, immediately after the end of Com-Battler V, this was technically Nippon Sunrise's debut work. Produced at Sunrise Studio 2, it inherited most of the same staff as its predecessor, including chief director Tadao Nagahama. The "Sunrise Anime Super Data File" describes it as follows:

The evil grasp of the planet Boazan is reaching out for Earth. Sensing this danger, Kentaro Goh secretly constructs the giant robot Voltes V. He entrusts it to his three sons, as well as Megumi Oka and Ippei Mine, who must now battle a Boazanian invasion force led by Prince Heinel...

Continuing the line of Com-Battler V, it featured five combining mecha. In this archetypal Nagahama robot show, the shocking revelation was that Kentaro Goh was actually the activist La Gour who called to eliminate the racial discrimination of the planet Boazan (in which horned people were superior), and Heinel too was one of his sons.

The main robot Voltes V was designed by Katsushi Murakami of Bandai's Popy subsidiary, the program's sponsor. As a planner and developer, Murakami had been responsible for a series of hits such as Popy's "Chogokin," "Popinica," and "Jumbo Machinder" toy lines. By the late 1970s, he was playing an active role in designing robots and mecha for the anime and live-action shows the toymaker was sponsoring, including Reideen the Brave and Com-Battler V. The popularity of the Leopardon, the super robot he designed for Toei's 1978 live-action Spider-Man, inspired the addition of Murakami-designed robots to the "Super Sentai" series as well.

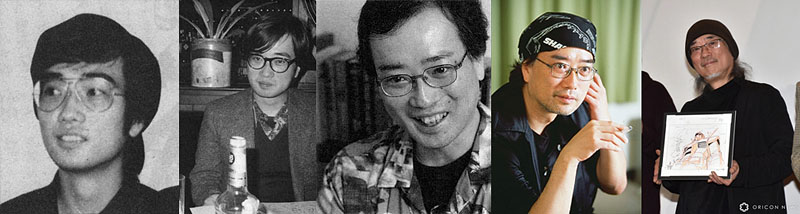

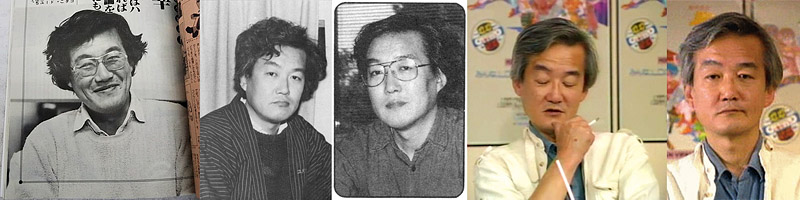

Left: Katsushi Murakami in 2002. Other photos are circa 2015 to 2017.

While his name seldom appeared in official credits, Murakami went on to become one of the major mecha designers of the 1980s. Following Popy's 1983 absorption into the Bandai Group, however, Murakami began moving into a management role. After he joined Bandai's board of directors in 1988, his direct involvement was generally limited to designing the robots' heads—including that of the main robot from 1992's Kyōryū Sentai Zyuranger, perhaps better known as the Megazord from Mighty Morphin Power Rangers.

By the time of Voltes V, Popy had effectively taken control of the robot design, which was decided early in the planning process. On Com-Battler V, the last-minute adjustments Nagahama and his collaborators made to the design had caused the toymaker considerable trouble, and they were ordered not to tinker with it in the followup series.

Tadao Nagahama — Roman Robo Anime Climax Selection

The design of the robot was completed before the somewhat unfocused story. In retaliation for Com-Battler, where we'd altered the appearance of the mecha ourselves, this time we had to follow it faithfully.

"Please don't mess around with the robot this time. That caused a lot of trouble in the manufacturing process on Com-Battler. We never want to go through that again."

...Well, that was a problem! Looking at the robot's face, it was just like a crow tengu. We couldn't say in good conscience that it was "cool." The elegance of the Reideen now felt like a dream... In that case, victory or defeat would be decided by the content! That's what I decided.

Rather than Studio Nue, as with previous Soeisha and Sunrise works, the newly founded design studio Mecaman was commissioned to provide supplemental mechanical setting.

☆ Click the image thumbnails below to see them at full size! ☆

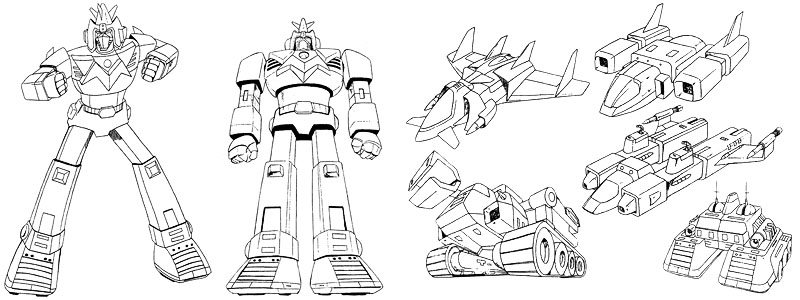

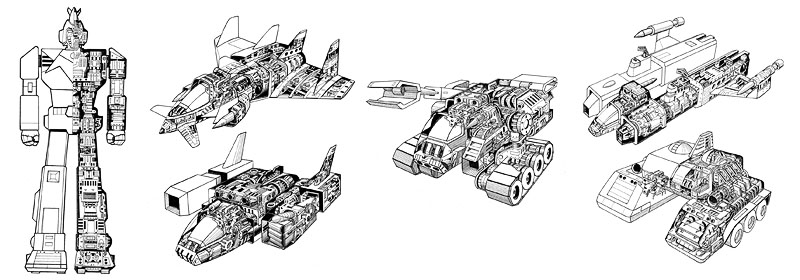

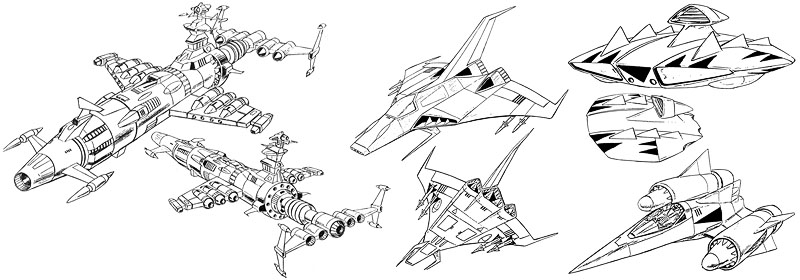

Final Voltes V, Volt-Cruiser, Volt-Bomber, Volt-Panzer, Volt-Frigate, and Volt-Lander setting art.

Internal cutaway diagrams by Kunio Okawara of Design Office Mecaman.

Akihiro Kanayama, a veteran animator who had worked as an animation director on every episode of Com-Battler V, debuted as a character designer on this series. In the 1980s he would largely return to animation work, serving as chief animation director on Sunrise's Trider G7 and Daioja, and working as an animation director on most of Yoshiyuki Tomino's TV series.

Left to right: Akihiro Kanayama in 1980, 1993, 2014, and 2018.

2014 photo is from this Anime News Network interview.

On Com-Battler V, the original character designs had been created by manga artist Makiho Narita and then cleaned up for animation by Yoshikazu Yasuhiko. With Voltes V, the original designs were by Yuki Hijiri, with Nobuyoshi Sasakado cleaning up the hero characters and Kanayama handling the villains. Hijiri and Kanayama would go on to handle the character designs for the rest of the Romantic Robo series.

Scenes from Voltes V's opening credits.

One notable aspect of Voltes V was its enduring popularity in the Philippines, where its subversive content ultimately led to it being banned from the airwaves on the orders of President Ferdinand Marcos. In 2023, a live-action remake titled Voltes V: Legacy aired on Philippine television.

無敵超人ザンボット3

無敵超人ザンボット3| TV BROADCAST | |||

| Nagoya TV • Saturday 5:30-6:00 PM October 8, 1977 to March 25, 1978 (23 episodes) |

|||

| MAIN CREDITS | Planning | Nippon Sunrise | Original story | Yoshitake Suzuki Yoshiyuki Tomino |

| Music | Takeo Watanabe Yushi Matsuyama |

Character design | Yoshikazu Yasuhiko |

| Mechanical design | Ryoji Hirayama | Chief director (総監督) |

Yoshiyuki Tomino |

| Producer | Yoshikazu Tochihira (Nippon Sunrise) Nobuyuki Okuma (Sotsu Agency) |

||

| Production | Nagoya TV, Sotsu Agency, Nippon Sunrise | ||

| ADDITIONAL CREDITS | |||

| Literature manager | Noboru Tateya | Art | Mitsuki Nakamura (ep.1~6) Mecaman (ep.7~23) |

| Design cooperation | Studio Nue | Production manager (制作デスク) |

Yutaka Kanda |

Super Machine Zambot 3 was the first original work from the reborn Nippon Sunrise. The "Sunrise Anime Super Data File" describes it as follows:

At the end of the Edo period, the Jin family secretly took refuge on Earth after their home planet Bial was destroyed by the murderous Gaizok. Here they've lived peacefully as a Japanese family, but a hundred years later, the Gaizok finally arrive on Earth. Reviving the spaceship King Bial and the giant robot Zambot 3 left to them by their ancestors, the Jin family fight off the attacking Mecha-Boosts that serve as the Gaizok advance force. But the people of Earth turn against the Jin family, blaming them for the Gaizok's attacks...

Though at first glance it seemed like an orthodox super robot show, this shocking work became a drama that directly showed the relativism of moral values, and the anger and sorrow of people who had lost lives and seen their homes burned in the fighting. Sunrise has continued to address these themes ever since, attempting to depict the true nature of war and of humanity itself. This was Zambot 3. With its first independently produced work, Sunrise was already taking its first step towards pioneering the "real robot" genre.

The development of Zambot 3 began with planning chief Eiji Yamaura. As he wondered how to distinguish Sunrise's offering from the many other robot shows on the air, Yamaura arrived at the slogan "the drama is high, the target is low," aiming the toy merchandise and the story content at different age groups.

Eiji Yamaura — Complete Works of Yoshiyuki Tomino 1964-1999

We'd been subcontracting for Toei ever since the days of Sunrise Studio. We did this at the time of Reideen as well, but we referenced the works of other companies and imitated them. The robot anime boom had been going a long time before Zambot 3, and by that point people were starting to say they'd had enough of robot shows. So we were racking our brains over how we could differentiate ourselves from Toei's works.

—Nowadays, people say that Zambot 3 was a trailblazer as a TV anime that was worthy of adult appreciation, but did you have that in mind from the planning stage?

It would be nice if we'd planned all that ahead of time, but it was all we could do just to figure out how to differentiate ourselves. In the process, we arrived at the concept of aiming the products at younger age groups, and the drama at older ones.

Eiji Yamaura — Zambot 3 / Daitarn 3 Chronicle

When we were producing Super Machine Zambot 3, our first independently created work, we had three points in mind.

First, "The drama is high, the target is low." That meant keeping the target age group young, creating works with highly dramatic content, and releasing toys at low prices. That should have been impossible based on previous data. In fact, we were supposed to create drama suitable for younger audiences, but we wanted to change that.

Next, "The toy shouldn't be different from the robot in the work." Even if they were inexpensive, we had to sell a lot of toys. So we thought the toys needed to faithfully reproduce the combination and transformation of the robot in the work.

And finally, "Let's promote the staff." This was exactly the point at which anime magazines appeared, so we thought we could shine a spotlight on staffers such as episode directors, scriptwriters, and animators who had previously worked entirely behind the scenes.

Indeed, despite the infamous lack of production resources, the Zambot 3 staff would ultimately include some of the anime industry's most outstanding rising talents.

Staff photos from the 1997 Zambot 3 Memorial Box booklet.

Top row: Ryosuke Takahashi (not a member of the Zambot 3 staff), chief director Yoshiyuki Tomino, planning chief Eiji Yamaura, scriptwriter Yoshitake Suzuki, character designer Yoshikazu Yasuhiko.

Bottom row: Mechanical designers Ryoji Hirayama and Kazutaka Miyatake, producer Yoshikazu Tochihira.

At the sponsor's request, the drama was based on the idea of a "family action" show, leading to the idea of a young hero close to the age of the toy-buying target audience. The relatively brief broadcast duration of two cours (roughly 26 episodes, or six months) was also decided at an early stage.

Eiji Yamaura — Roman Album 21: Super Machine Zambot 3

Zambot was being planned as the second of our robot shows. When we drafted the original plan, there were a lot of combination shows, and the original idea was that five mecha would transform and combine. But the problem remained of how to establish the characters for this work, and since the sponsor side requested we make them "a family with some new kind of blood relationship," we created the basic setting accordingly.

In the character setting of other robot shows, the main characters seemed to be roughly 15 to 20 years old. But this time, since we wanted them to be relatable to the children watching TV and the drama would focus on family action, we went ahead and lowered their ages. We decided to make the hero the youngest child in the family, and thus Kappei was created.

Yamaura's initial idea of a five-part combining robot was simplified into a three-part combination, to ease the burden on both Clover's engineers and Sunrise's animators. Veteran screenwriter Yoshitake Suzuki was commissioned to write a proposal based on this concept.

Yoshitake Suzuki — Roman Album 21: Super Machine Zambot 3

At the time, I had a different plan that preceded Zambot, which I'd written while holed up at a hot spring resort in Chichibu. It was supposed to become an anime, but nobody wanted it. They said it was too influenced by the earlier work Reideen.

Yoshitake Suzuki — Zambot 3 / Daitarn 3 Chronicle

At the point when the planning of Zambot began, I was involved with Sunrise as a writer and a planning brain, in a role like that of a sounding board for Mr. (Eiji) Yamaura. Mr. Yamaura would talk to me about what he'd come up with as a planner, and he'd ask me "Please put something together." Then Mr. Yamaura would give his opinion again based on what I'd written. Through this kind of back-and-forth, we'd gradually settle on a plan.

Suzuki and Yamaura proceeded to complete a proposal for the new series, which Suzuki describes as "a soft, family-oriented sentai show." This proposal would later be revised with the input of its chief director.

Yoshito Sakai — Zambot 3 / Daitarn 3 Chronicle

The content of the "Zambot 3" proposal was generally similar to the completed work. The heroes were collectively known as the Jin family, with the protagonist Tempei Jin (age 12) supported by a cheering squad of three sisters named Yuri, Michi, and Aki, as well as his kid brother Sampei. Though there were subtle differences, many elements that were carried over to the actual work were already established at this stage, such as "the protagonist's family are descended from space aliens," "three mecha scattered across Japan," "a transforming combat robot with lots of variations controlled by the boy protagonist," and "the true enemy is actually a giant computer."

On the other hand, some important dramatic elements of Super Machine Zambot 3, such as "the protagonists are persecuted by the general public" and "a structure where good and evil are reversed," weren't yet incorporated at this stage. These ideas came from Yoshiyuki Tomino, who was appointed as director of this work in June 1977.

Super Robot Generation Sunrise 1977~1987

On the cover of the proposal, the title of the work is written as "Zambot 3" without a subtitle, but inside the proposal it's written "Unchallengeable Zambot." In this proposal, the mecha corresponding to the Zambo-Ace is tentatively named the "Sumo-Zambo," and the Zambase is the "Zamborg." The protagonist Kappei Jin is named "Tempei Jin," and the other characters all share the same "Jin" family name.

The storyline described in the proposal is almost identical to the broadcast version, but there's also the idea of depicting discord within the Jin family as some of its members, afraid of battle, plan to escape from Earth. Aside from this proposal, there's also another one by director Yoshiyuki Tomino.

"SF Robot Action Zambot 3" proposal. Though this is dated 1977, it's unclear whether this is the original proposal by Yoshitake Suzuki, or the revised version by Yoshiyuki Tomino. The production is credited to the Tōyō Agency, the planning company Big West, and Nippon Sunrise.

The title went through several permutations, including "Unchallengeable Zambot" and "Zambot Moon," and was based on a multi-layered pun. As usual, Masao Iizuka of the Sunrise planning office provides the inside story...

Masao Iizuka — Zambot 3 DVD Memorial Box

We invented a coined word based on the ridiculous ones Mr. Yamaura uses. Most English words are already registered, so you can't trademark them. Mazinger Z had already used "majin," but we were really impressed by Tatsunoko's "Time Bokan" series, and we decided to go with a name like that. The name "Zambot" comes from "San-Robot" because it's a Sunrise robot and the robot is formed from three mecha. But that seemed somehow inadequate, so we decided to add "three" to the robot's name. The president of Clover also asked us to give it the subtitle "Unchallengeable Robot," but we refused. (laughs)

—Was that because it would have been redundant to say "bot" twice?

Right. And what's more, now we'd finally managed to get a sponsor, we wanted to keep going for at least two or three works. Since it was descended from aliens, we decided to call it an "Unchallengeable Superman" surpassing the people of Earth.

We wanted to do an "Iron Man" next, but since there was already an Iron Man 28, we had to come up with something else and we used "Steel Man" for the Daitarn 3. When the time finally came for us to use "robot," we fulfilled the wishes of Clover's president by calling the Trider G7 "Unchallengeable Robot."

Yoshiyuki Tomino — Zambot 3 DVD Memorial Box

The idea behind the naming method was similar to what Toei Doga had been doing ever since Mazinger Z. Of course, we wondered whether we could create something new instead, but practically speaking we couldn't come up with a better naming idea. Because there were three things that combined, we shamelessly decided to add a "3."

The design of the robot itself was entrusted to new Sunrise employee Ryoji Hirayama (now known as Ryoji Fujiwara), previously an aspiring manga artist, who was initially assigned to the planning office. During the production of Reideen the Brave, the planning staff had decided to model the robot on an armored samurai warrior, and they used the same approach on Zambot 3.

Masao Iizuka — Zambot 3 DVD Memorial Box

When I asked the children about their favorite colors back then, they said "red, blue, and white," the so-called tricolors. Since it's a helmet and armor, the decorated parts should be gold, but that's not a cel color so we made them yellow. That's how we arrived at the Reideen. We looked into it again when we started on Zambot, and there still wasn't anything else like that, so we went with a Japanese warrior and tricolors again. That's how we started out.

—There are a lot of surviving rough designs of the robot.

At first, we were combining blocks and pillars to come up with a three-dimensional design that could be exactly reproduced as a toy. However, that wouldn't work as an object of childrens' desires to metamorphose and get bigger. Though it was a robot, it was still animation, so of course it had to have a personality as a character. Thus we had Mr. Yasuhiko rewrite it for us, just like with Reideen.

—Mr. Ryoji Hirayama (now Ryoji Fujiwara) is credited for the mecha design, isn't he?

He used to be an assistant to the manga artist Mr. Satoru Ozawa (the creator of Submarine 707). We said "Then you can design mecha, right?" and he said "No, I can't draw robots and stuff, I'm no good at drawing." We persuaded him by saying "Don't worry, if we give it to Mr. Yasuhiko, he can rewrite it for the anime." (laughs)

Ryoji Hirayama — Great Mechanics G 2018 Autumn

I started out by joining the Nippon Sunrise (now Sunrise) planning office. But even though I was in the planning office, at first there was nothing for me to do. (laughs) I remember the planning office chief Mr. Eiji Yamaura, who later became the president of Sunrise, was just reading books all the time, and for a while he didn't give me any instructions.

—How did you end up joining the planning office?

Before I joined Nippon Sunrise, I was apprenticed to a certain manga artist, who had me doing things like box art for a plastic model series he was working on. So I quit and started doing part-time work. Then an acquaintance I'd made through doing box art, Section Chief Kiyomi Numoto (originally of Mushi Pro, and one of Sunrise's founding members) of Takara (now Takara Tomy), referred me to Nippon Sunrise. I don't even remember whether I was a company employee at the time. (laughs) They were just paying me enough to survive, but I was planning to get married, so I was grateful to have a salary. (laughs)

—What kind of work were you doing at first?

None at all. Since I'd been given no instructions, I just spent every day in idle chatter. So Mr. Masao Iizuka (later manager of the Sunrise reference room) said "I'm going to teach you the basics of anime," and he took charge of me. I'm truly indebted to Mr. Iizuka for that.

After I'd spent about half a year assisting Mr. Iizuka, Mr. Yamaura suddenly asked me to think up a robot. When I asked him what he wanted, he said "Come up with a gimmick where three or so mecha combine."

Faced with the unexpected challenge of designing the new robot, Hirayama initially focused on the transformation and combination gimmicks. It's sometimes been claimed that mechanical designer Kunio Okawara came up with the basic design for the combination, but Okawara himself says he wasn't involved, and according to Hirayama he worked it out himself with some help from the engineers at Takara.

Ryoji Hirayama — Great Mechanics G 2018 Autumn

After that, aside from the design details, I finalized it with Mr. Yamaura and the others, saying things like "Let's try adding wings." We got it into a form that could more or less combine. Meanwhile, I remember they told me to go to Takara to discuss whether or not they could turn it into a toy.

—So they sent you to Takara by yourself, even though you were still a new employee in your early twenties?

That's right. Nobody else came with me. (laughs) I went by myself, and I heard the opinions of the Takara people, which were like "You can do this, you can't do that." Through these conversations, we refined it further and finally arrived at something we were confident could combine properly.

I think at first, we hadn't yet decided what kind of mecha were going to combine. As I was thinking about the combination, I created them by saying "This should be this shape." Then, as I thought about how the mecha would combine, I was simultaneously deciding on the types and characteristics of the combining mecha, saying things like "The back feels lonely in design terms, so let's add caterpillar tracks and make that a mecha that travels underground." I think requests for an aircraft and a tank came up along the way.

I made the robot first, and then divided it up into three parts. As I was working on that, I got stuck on one of the parts. I spontaneously thought "This could turn into a humanoid form" and made it that way. I think I simply said something like "Couldn't a head pop out of here?" But I was worried about how that would work in the toy. (laughs)

Hirayama ultimately arrived at a three-part combination of a tank, a large aircraft, and a fighter plane that transformed into a smaller robot. At first, he intended the tank component to transform into a small robot as well, but this gimmick was eventually eliminated.

☆ Click the image thumbnails below to see them at full size! ☆

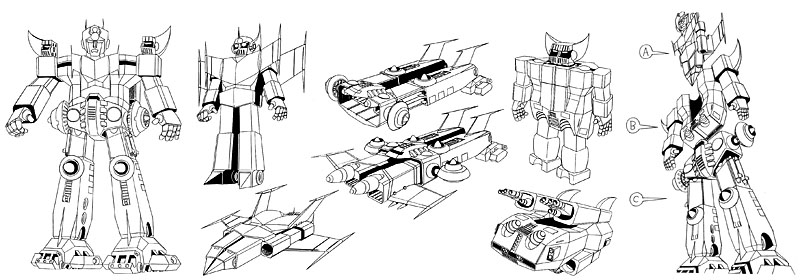

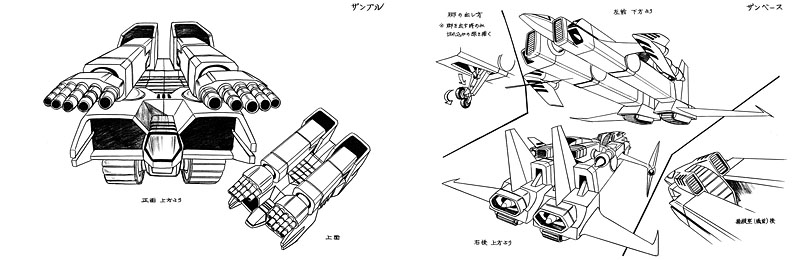

Early designs for the Zambot and its component mecha by Ryoji Hirayama.

Meanwhile, initial drawings of the heroes were created for presentation purposes. It's unclear who drew these, but the "Zambot 3 Archives" book included with the 2003 DVD Memorial Box attributes them to manga artist Mitsuru Hiruta, who would later contribute behind the scenes to the design of Zambot 3's enemy mecha.

Early versions of the Zambot 3 protagonists, possibly by manga artist Mitsuru Hiruta.

With the proposal complete, preparations began for the show's production. The cramped Sunrise Studio 3, which had been dormant since Dinosaurs Catcher Born 3, was to be the production site. Part-time employee Yoshie Kawahara—then assigned to Studio 1 to support the production of Robokko Beeton—was tasked with tidying it up.

Ryoji Hirayama — Great Mechanics G 2015 Autumn

This was some time after Robokko Beeton entered its second half. I don't recall exactly when this was, but it was probably in the spring, since the weather was neither hot nor cold.

"Sorry about this, Hiroppe, but could you clean up Studio 3?"

Mr. Iizuka, who would later become my official boss, was then singlehandedly running the planning desk, materials management, and publicity. He'd led me up the narrow stairs of a building right in front of the train station, which housed a grocery called "Yaoshō." This was Studio 3, then known as the "Kum Studio," which had produced Kum Kum and the later Dinosaurs Catcher Born 3.

It was even more cramped than Studio 1, on the second floor above a coffee shop. It was a space with a sink and a one-room closet, and bumpy vinyl floor tiles. But what surprised me the most was that, cramped as it was, there were cut bags piled up all over the floor about as high as my waist.

"We're going to be using this place soon, so could you tidy up these cels? Beeton should be fine for the time being, so I'd like you to organize the cels in the meantime."

I honestly felt faint just looking at this vast amount of material...

For roughly the next two weeks, I spent my days wrestling with about 78 episodes' worth of cels (249,600 by my rough estimate, hah) from Kum Kum and Born Free. I had no idea this would later become my own workplace. The cramped first-generation Studio 3, with its bumpy floor, was to become the production site for Super Machine Zambot 3, Sunrise's first original program.

According to the 2003 book "Zambot 3 / Daitarn 3 Chronicle," the production of Zambot 3 was approved around June 1977, when the broadcast of Voltes V began. Kawahara was transferred back to Studio 3 to manage and support the production site, and found mechanical designer Ryoji Hirayama still toiling away on the design of the robot's head.

Yoshie Kawahara — Great Mechanics G 2015 Winter

Studio 3, which had previously been filled with mountains of cels, was now outfitted with desks and shelving, making it a small but respectable-looking studio. Mr. Ryoji Hirayama (now Ryoji Fujiwara), for whom this work was his first animation job, was already sitting at a drawing desk in the back. The design of the Zambot's head hadn't yet been decided, so Mr. Hirayama, who was also a manga artist, had drawn countless designs and lined them up. He was really mild and humble, and he even asked me which I thought were best.

At first it was pretty much just the two of us in the studio, but soon the rest of the staff began to appear one by one, and the production of Zambot began in earnest.

It's unclear who first proposed the Zambot 3's distinctive crescent moon-shaped forehead decoration. In his DVD Memorial Box interview, Masao Iizuka says he initially suggested antlers like those of Yamanaka Shikanosuke, and explains that the final design was inspired by the hero's crescent-shaped scar in the historical novel and movie series Bored Hatamoto, as well by as the helmet of Date Masamune.

A few of Ryoji Hirayama's many Zambot head design variations.

One of the first people Sunrise approached to work on Zambot 3 was the multitalented Yoshikazu Yasuhiko. But Yasuhiko, who was still recovering from his heavy workload on Robokko Beeton and now had his hands full storyboarding a new Space Battleship Yamato feature film, was reluctant to commit to another animation direction job. His role was limited to character design, and Sunrise decided not to appoint any animation directors at all—a decision so offensive to Yasuhiko that he refused to watch the show on principle.

Yoshikazu Yasuhiko — Zambot 3 DVD Memorial Box

One thing that bothered me was the fact they hadn't appointed an animation director. I complained to Mr. (Eiji) Yamaura about it, saying this work should be a valuable asset in the future. They had proper animation directors for Com-Battler V and Voltes V, which they were making as subcontractors for Toei, so it seemed strange that they didn't have them for their own original work.

—Was that another reason why you only participated as a character designer?

That wasn't it. At the time, I was really busy working on Farewell to Space Battleship Yamato, so it would have been physically impossible for me to do both at once.

—You must have wanted to be involved.

Of course, if it were possible, I'd have wanted to do it. After all, I'm attached to the characters I create. But it was totally out of the question. So I asked what they were going to do about an animation director, and they said that if I couldn't do it, they wouldn't appoint one. I was a little sad to hear that. It was like they were saying our job was so trivial it could be done without us.

Yoshikazu Yasuhiko — Zambot 3 / Daitarn 3 Chronicle

An animation director is a supervisor who maintains the drawing quality for each episode, and it's an really important position in anime production work. But when it came to Zambot 3, I declined to take on the animation direction as well, since I didn't have the capacity. They replied "That's okay, we just won't appoint an animation director."

As a character designer, I wanted them to properly appoint an animation director to maintain the quality. I was still young back then, only in my twenties, so I rebelled against this and refused to watch it.

Yasuhiko set to work designing Zambot 3's cast of characters based on the rough concepts in the proposal, with some guidance from the Sunrise planning department. His initial impression that the story would be lighter and more gag-focused was reflected in the designs, and Yasuhiko later realized they didn't quite match the serious tone that Zambot 3 gradually took on.

Yoshikazu Yasuhiko — Zambot 3 / Daitarn 3 Chronicle

When I started drawing the characters for Zambot 3, although there was a proposal, nothing more than a rough story had been created. They hadn't yet firmed up the detailed setting or the specifics of what kind of story it would be. But it was normal to draw the characters before it had been decided how everything would turn out, or what the work would be like.

With anime shows, especially robot anime, the designs usually come first. The first thing to be completed is the main robot, which is going to be turned into a toy. That's because the toymaker will already have finished it. Then the plan itself can be completed afterwards. Even with Zambot 3, the toy design was done first, and then we were just supposed to use it as is.

After the robot aspects were finalized, we'd start creating the worldview and characters. I'd list all the characters and begin designing them based on the rough story development. Typically, at the point when I received the orders, only the characters' general personalities and the relationships between them would have been decided.

Masao Iizuka — Zambot 3 DVD Memorial Box

Back then, children were still the mainstream audience for anime. We really wanted to attract them, so we wanted the protagonists of Zambot to be close to elementary-school age. We wondered if that was implausible, but we figured it was okay if they were descended from aliens, and the whole thing started from that nonsensical place. (laughs)

We told Mr. Yasuhiko "It's fine for Uchuta and Keiko to be age-appropriate, but even if they were high-schoolers, some of those are still as small as middle-school students while others are growing beards." So we asked him to make the protagonists as childlike as possible. We made Kappei a middle-schooler as well, but sooner or later we really wanted to target grade-schoolers, and we were finally able to achieve that with the later Unchallengeable Trider G7.

Yoshikazu Yasuhiko — Zambot 3 Memorial Box

Initially, I wasn't told anything about what kind of story it would be, and I had the impression it would be more gag-focused. Before Zambot 3, I'd also been working on Robokko Beeton, a gag show with characters three heads high. I hadn't shaken off those habits yet, so when I drew Kappei and the others, they ended up being relatively manga-like characters with short legs.

As the story got more and more serious, I was not only surprised, but I also thought I'd made a mistake. If I'd known from the beginning it would be this kind of story, I thought, I'd have made characters who could support slightly more serious dramatic performance.

The incoming chief director, however, did give Yasuhiko some feedback on the characters' proportions...

Yoshikazu Yasuhiko — Zambot 3 / Daitarn 3 Chronicle

It was Mr. Tomino's order that the Zambot 3 characters should be in a manga style with shorter proportions, five or six heads tall. I also preferred the manga style to the gekiga style, so I enjoyed drawing them. But I made the legs of the protagonist Kappei too short, and I remember Mr. Tomino asked for a revision, saying "Can't you make his legs a little longer?"

☆ Click the image thumbnails below to see them at full size! ☆

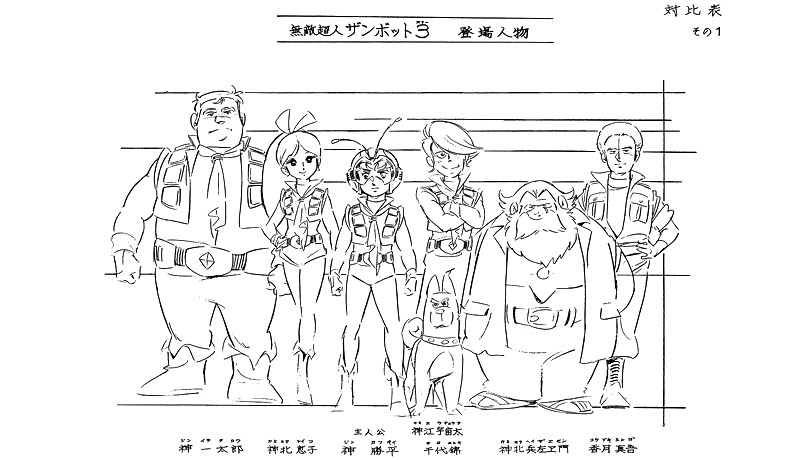

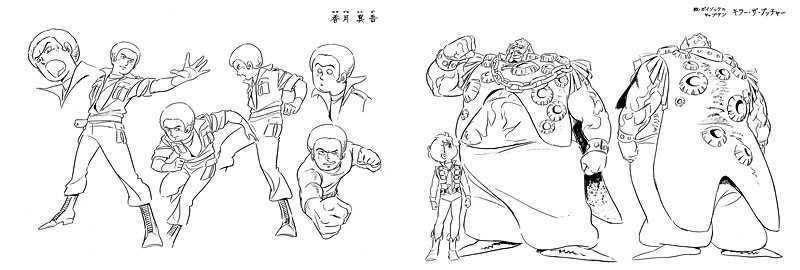

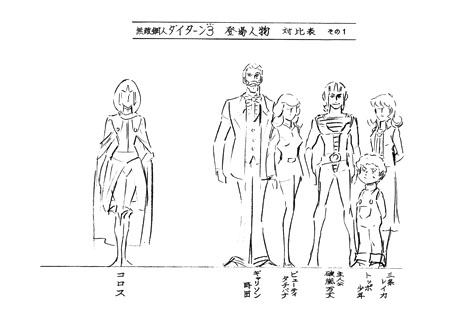

Zambot 3 character comparison chart by Yoshikazu Yasuhiko.

Kappei Jin, Uchuta Kamie, and Keiko Kamikita character setting art by Yoshikazu Yasuhiko.

Members of the extended, multigenerational Jin family: Heizaemon Kamikita, Umee Jin, Ichitaro Jin, Gengoro Jin, and Hanae Jin setting art by Yoshikazu Yasuhiko.

Two very different types of antagonist: Shingo Kozuki and Killer The Butcher character setting art by Yoshikazu Yasuhiko.

Another key member of the creative team was chief director Yoshiyuki Tomino. After his humiliating ejection from Reideen the Brave, Tomino had continued working on the series under new chief director Tadao Nagahama, and went on to direct episodes of Nagahama's Com-Battler V and Voltes V in order to study his replacement's techniques. Directing Sunrise's first original work would be a clear opportunity for redemption.

Eiji Yamaura — Complete Works of Yoshiyuki Tomino 1964-1999

To be perfectly honest, at that point we weren't such a big company, and we weren't in a position to ask anyone for help. But it seemed possible that he'd do it for us. Of course, we were also confident that he could make a good work. As the first work of a new company, it absolutely had to be successful, and to put in a way that sounds cool, he was the only one who could do that.

We had a high opinion of him as a series director from when he was working on the first part of Reideen. He'd been removed after episode 26, but I was the one who'd removed him. There's nothing I hate more than having to remove someone even though you value their abilities, and I still regretted it. So I had no worries at all about entrusting him with Zambot 3. I knew I could rest easy relying on the person who did the first part of Reideen.

Yoshiyuki Tomino — Zambot 3 / Daitarn 3 Chronicle

Actually, three days before they approached me about Zambot 3, I'd accepted the job of chief director on an anime based on a preexisting original work. But when I was asked to direct Zambot, I turned the other one down. In the end, I thought I'd benefit from a situation where I could write an original story and develop my own skills. If there's a pre-existing work, you're always more constrained. But when I called and said "I'm sorry, I'd like to step down," naturally they didn't give me any more work for a while. (laughs)

Eiji Yamaura — Zambot 3 / Daitarn 3 Chronicle

Tomino-chan wasn't involved from the beginning, but he joined us as a director at the point when the proposal was completed. I think that was around the time Yasuhiko-chan's characters were finalized.

Yoshiyuki Tomino — Zambot 3 DVD Memorial Box

It started out with just Mr. (Yoshitake) Suzuki, Mr. Yasuhiko, and Mr. (Eiji) Yamaura. I was the last one to join the planning. As a director, I understand they had no choice but to call me in, and that's certainly what it felt like.

—Did you feel a lot of stress at the time?

I didn't, because that's part of the job. If you aren't at the level where you can handle a program picture—in other words, a show you're shooting on that kind of schedule—then you're a student or an amateur.

—Were the characters already taking shape before you joined?

Since I was the last member to join, some of them had already been finalized according to Mr. Yasuhiko's visualization, and it was my job to accept all of that.

The basic premise of the show, as well as the designs of the characters and the main robot, had been largely decided by the time Tomino joined the Zambot 3 staff. Nonetheless, he threw himself into planning the story, and his contributions were so substantial that Sunrise decided to give him an "original creator" credit alongside scriptwriter Yoshitake Suzuki.

Yoshitake Suzuki — Complete Works of Yoshiyuki Tomino 1964-1999

At first I was creating the plan with Mr. Yamaura, but as we were working on it, we realized the extent of his abilities. He's so fast at drawing storyboards, and he also has a certain decisiveness as a director. For example, when you're wondering which option to choose, or what you should do and how you should do it, I do that at a slow pace, saying "Hmmm..." Mr. Tomino just decides instantly. I told him he was good at making decisions, and he said "Just because I made a decision doesn't mean I thought about it."

With that kind of ability, I thought it might be better to put him in the position of original creator rather than just an ordinary director, and I said to Mr. Yamaura "Let's make Tomi-chan an original creator." So Mr. Tomino joined me in that role partway through.

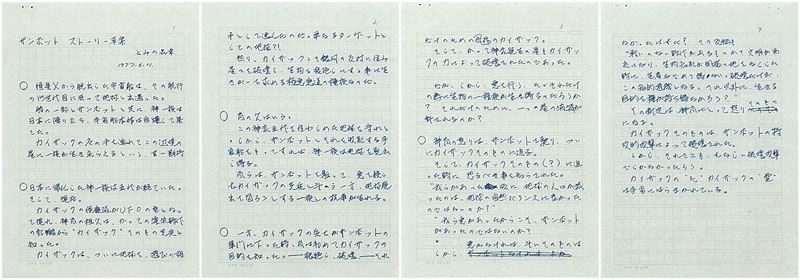

An early "Zambot Story Plan" by Yoshiyuki Tomino. This manuscript is dated June 11, 1977, shortly after Tomino joined the Zambot 3 staff.

The planning and design group Studio Nue—which had provided science fiction research support on 0-Tester, Reideen, and Com-Battler V during the Soeisha era—was also recruited to assist with the development of Zambot 3. Writer Haruka Takachiho served as the liaison between Sunrise and Nue, while designer Kazutaka Miyatake contributed sketches and concept drawings.

Haruka Takachiho — Great Mechanics G 2017 Autumn

I think it was in the heat of summer when Mr. Yamaura told me "We're planning something with Mr. Tomino, so come on by." I went to the planning office, and I talked there with Mr. (Yoshitake) Suzuki, Mr. (Yoshikazu) Yasuhiko, and Mr. Tomino. But I don't really recall the details, and I didn't contribute much to the proposal. When things got going, Miyatake did designs for the base mecha, but the only ideas I provided were the name "Killer the Butcher" and giving the Zambot a sai as a weapon.

Kazutaka Miyatake — Zambot 3 Memorial Box

Although we were credited for "design cooperation," on Zambot 3 we were actually involved in most of the main and secondary mecha design, from the Zambot itself to the King Bial and the Bandock. As an aside, that's why the various close-combat weapons with which the Zambot 3 is equipped, starting with the Zambot Grap and the Zambot Cutter, strongly reflect the tastes of Haruka Takachiho, who is now a novelist but served as the contact person on the Studio Nue side during the production of Zambot 3.

While Takachiho contributed story and setting ideas, Miyatake helped refine the design of the main robot Zambot 3 and its component parts—the Zambull, the Zambase, and the Zambird fighter that transformed into a smaller robot called the Zambo-Ace. He was also responsible for designing their cockpits, and planning out the launch and transformation sequences for animation reference.

☆ Click the image thumbnails below to see them at full size! ☆

Zambot 3 rough designs by Kazutaka Miyatake of Studio Nue. The leftmost sketch shows a strong influence from Com-Battler V. The horns on the head of the other version were apparently Haruka Takachiho's idea.

Near-final versions of the Zambot 3 by Ryoji Hirayama. The design was almost complete at this point, but it remained undecided whether the robot should have an exposed face.

Zambo-Ace rough designs by Kazuya Miyatake, which underwent proportion adjustments at the request of chief director Yoshiyuki Tomino. The waist-mounted Zambo-Magnum was modeled on Napoleon Solo's firearm in The Man from U.N.C.L.E.

Rough sketches of the Zambird, Zambull, and Zambase by Kazutaka Miyatake. The Studio Nue staff also came up with a variety of built-in weapons for each vehicle.

Mechanical designer Kunio Okawara, who wouldn't begin working with Sunrise in earnest until 1978's Daitarn 3, contributed a concept for the heroic family's three-part combining base that was later repurposed for the enemy fortress Bandock.

☆ Click the image thumbnails below to see them at full size! ☆

An early concept for the heroes' base by Kunio Okawara. It's designed to separate into three parts, each of which is shown holding one of the Zambot 3's component mecha—note that the designs of the latter are very close to the final versions. Marker sketch on left is dated June 11, 1977.

Kazutaka Miyatake's rough sketches of the Bandock, which had now been turned into an enemy fortress. Since Okawara's design was only a front view, Miyatake was responsible for designing the rest of its body.

The Studio Nue staff were also responsible for coming up with weapons for the Zambot 3 and its component mecha. Takachiho, who had an extensive personal collection of exotic weapons, posed with them to provide Miyatake with drawing reference. Last but not least, Miyatake designed the three-part combining spaceship King Bial, which served as both a mothership and a home for the heroic Jin family.

☆ Click the image thumbnails below to see them at full size! ☆

Weapon and pose ideas by Kazutaka Miyatake, for which Haruka Takachiho served as a model.

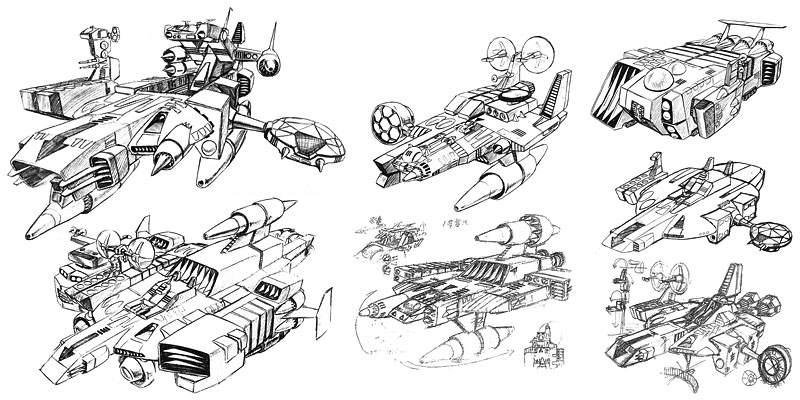

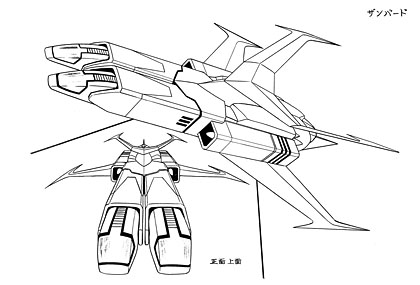

Rough designs for the King Bial and its components, the Bial I, Bial II, and Bial III, by Kazutaka Miyatake. This spaceship wasn't originally intended to be turned into a toy, and chief director Yoshiyuki Tomino told Miyatake "I want an SF spaceship, not an anime-style warship."

Miyatake's vehicle designs were cleaned up by Ryoji Hirayama to create the final setting for animation purposes. Character designer Yasuhiko, meanwhile, performed the final cleanup on the Zambot 3, and provided a gallery of dramatic action poses for the Zambot 3 and Zambo-Ace.

☆ Click the image thumbnails below to see them at full size! ☆

Final Zambot 3 setting art by Yoshikazu Yasuhiko.

Final Zambo-Ace, Zambird, Zambull, and Zambase setting art by Ryoji Hirayama.

Final King Bial, Bial I, Bial II, and Bial III setting art by Ryoji Hirayama.

As Super Machine Zambot 3 entered full-scale production, producer Yoshikazu Tochihira scrambled to assemble a staff. His task was complicated by the fact that Sunrise's best staff were already committed to the subcontracting work the company was doing for Toei's own robot shows.

Yoshito Sakai — Zambot 3 / Daitarn 3 Chronicle

The Sunrise producer in charge was originally supposed to be Tohru Komori, the production supervisor on Star of La Seine (1975), for which Sunrise Studio had provided production support. For various reasons, however, Sunrise had to start over from scratch. Ultimately the role was assigned to young Yoshikazu Tochihira, previously of Tatsunoko Production, whose experience included being chief production manager on Tatsunoko's giant robot anime Gowapper-5 Gordam (1976).

Yoshikazu Tochihira — Zambot 3 Memorial Box

I left my previous job at Tatsunoko Pro in 1976, the year before "Zambot 3" began airing. Immediately afterwards, then-President Kishimoto invited me to join Sunrise as an assistant producer on Robokko Beeton. My impression at the time was that the company had a relaxed atmosphere that didn't seem very businesslike. Back then, Sunrise was a small production company that mainly provided production support for other companies, and it had probably inherited a strong influence from Mushi Pro, which was a creative group. But I was used to Tatsunoko Pro, which was really corporate, so I sometimes found it bewildering.

Though they went on to give me the title of producer on Zambot 3, President Kishimoto was effectively the general producer, and it felt like I was purely managing the production on site. I scraped together staffers from all over, but organizing this staff was really difficult. At the time, Sunrise's main staff were devoted to Com-Battler V and Voltes V, so most of our staff had to be newly assembled. I remember that I and the production manager Mr. Yutaka Kanda had tremendous trouble doing that. When I look back now on that staff list, I'm deeply moved to think we had such people working with us.

Yoshito Sakai's production history in Zambot 3 / Daitarn 3 Chronicle provides extensive details on Zambot 3's staff, including the writers, episode directors, and voice actors. Particularly noteworthy, though, are the music by Takeo Watanabe and Yushi Matsuyama—a teamup that would continue on Daitarn 3 and Mobile Suit Gundam—and the efforts of outside animation studios such as Green Box and Studio Z. Animator Yoshinori Kanada of Studio Z, in particular, drew praise even from Yasuhiko for his striking work on this series.

Yoshito Sakai — Zambot 3 / Daitarn 3 Chronicle

Studio Z in particular provided young talents such as the animator Yoshinori Kanada, who was then becoming recognized throughout the industry for his exceptional ability, as well his fellow animators Kazuo Tomizawa, Osamu Nabeshima, and Masakatsu Iijima, and the episode director Shinya Sadamitsu. The images they created onscreen with their unique sensibilities and bold techniques became one of Zambot's charms.

Yoshikazu Tochihira — Zambot 3 Memorial Box

Although I brought in various animators, Mr. Yoshinori Kanada of Studio Z really stood out. Frankly speaking, Studio Z's drawings were clearly different from the character sheets, but the completed key art was so wonderful that everyone else accepted them by saying "Studio Z is bespoke."

Yoshikazu Yasuhiko — Zambot 3 DVD Memorial Box

Mr. (Yoshinori) Kanada and Studio Z really worked hard under the difficult conditions of having no animation director. Mr. (Nobuyoshi) Sasakado, who was responsible for the final episode, also did a really great job. I think this work drew attention thanks to the efforts of such staffers.

And conversely, the fact that there was no animation director let them work more freely. This brought out some powerful images in the series, which the young staffers were able to create without restraint.

In a roundtable interview for the 2003 DVD Memorial Box, Masao Iizuka of the planning office reminisces with the former production assistants Yumiko Tsukamoto and Yoshie Kawahara (identified here by her alias "Hiroshi Kazama") about the challenging circumstances of Zambot 3's creation.

Masao Iizuka, Hiroshi Kazama & Yumiko Tsukamoto — Zambot 3 DVD Memorial Box

Kazama: I don't remember well, but maybe it was episode 2... it was around the beginning, but the schedule was already terrible.

Iizuka: We didn't have any decent production assistants, and the animation and finishing weren't properly set up yet, so we were just calling anyone who was free and asking for help on an ad-hoc basis.

Kazama: When the Zambo-Ace dives into the sludge, it was left unpainted so that you could see the background colors. We thought that was overdoing it, and then Mr. Tomino suddenly grabbed some cel paint. He said "This stuff is supposed to be slushy, so it's okay if it's slushy," and he started mixing together a bunch of different paint colors. (laughs)

Iizuka: We'd finished up to about episode 4 before it started airing. The opening, though, was done after that.

Kazama: Normally, you're supposed to use your best staff for the opening and ending. But that time, aside from the key art, it was a real mishmash.

Iizuka: Even if we'd tried to outsource it, no animators would take it. So we had no choice but to do it in-house.

Kazama: I think it was episode 14 when Tsukamoto-chan had to do the in-between checking, as well as looking over all the artwork like an animation director.

Tsukamoto: I did that for about two episodes. I honestly thought I was going to die.

Nonetheless, the work got done, and Super Machine Zambot 3—the first original independent work from Nippon Sunrise—made its television debut on Nagoya TV on October 8, 1977.

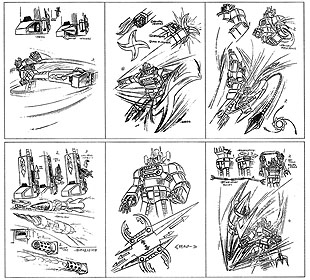

Scenes from Zambot 3's opening credits.

As the series continued, chief director Tomino's ambitious vision for the story gradually became apparent. During the ongoing battle against the invading Gaizok, the people of Earth turned against the heroic Jin family, blaming them for the resulting destruction. Then the enemy resorted to an even more brutal tactic with the introduction of the infamous "humans bombs."

Yoshitake Suzuki — Zambot 3 Memorial Box

As he gradually drew it into his own world, it went in what you could call a more Tomino-style direction. With the human bomb storyline, for example, at some point Director Tomino implemented it by declaring not "I'm thinking of doing this" but "I've done it." At the time, I thought it was only a passing whim, and I had no idea it would have such a huge impact on the narrative.

Yoshiyuki Tomino — Complete Works of Yoshiyuki Tomino 1964-1999

They told me off about this later, but right after it had finished airing, the company president and the executives showed up and said "You didn't do a story about human bombs, did you?" I said I hadn't, and I didn't tell them until after it had aired. I'd already sent them the script and storyboards, and I'd told them to check those if they had any complaints.

—Were the human bombs part of the setting from the very beginning?

No, they weren't. But as control over the content was gradually transferred to me, I decided to go for it. There'd be no point in them saying anything after it aired. I'd sent around a request for approval, but I never promised I wouldn't show anyone the script. So don't complain, I said! That's the sort of silly, funny thing that happened on Zambot 3.

—Was it because you were on Nagoya TV that you were able to do things like that with Zambot 3?

Of course. If it had been TV Asahi, they'd have checked it at the script stage, and the producer would have come rushing in to ask if we were serious. In those days, the people at the local broadcast station weren't yet sure how involved they should be in the making of the show, so nobody said anything.

—So you didn't hear anything from Nagoya TV when you did the episode with the human bombs?

Not a word.

Yoshitake Suzuki — Complete Works of Yoshiyuki Tomino 1964-1999

Anyway, it seems like harder stories like the human bombs increased the ratings to a certain extent. I think in the back of his mind, he always has the notion that "I won't get my next job unless I get good ratings," and that may be one of the factors that leads him to make those kinds of decisions. But the excuse he gives is that "Sunrise works have always been violent."

Meanwhile, the production situation gradually improved, and more skilled directors and animators joined the staff rotation. Since Sunrise Studio 1 was now vacant, it was put to use as an additional Zambot 3 production site, and by the end of the series the team had largely relocated to Studio 1.

Yoshie Kawahara — Great Mechanics G 2016 Spring

Starting in the middle of production, Studio 1, which had just finished the production of Robokko Beeton, was also put to use as a work site. It went on to become the production site for the followup work, The Unchallengeable Daitarn 3. Personally, I was responsible for the management of Studio 3, which remained the contact point for the Zambot production site until the very end, and I had to answer outside phone calls as well. So during this time, I seldom went to Studio 1. But I remember the preview screenings of Zambot's final episode and the first episode of Daitarn were held there, as well as the Zambot wrap party.

Yoshie Kawahara — Great Mechanics G 2015 Winter

With Studio Z joining in on the animation, and Mr. Shinya Sadamitsu and Mr. Kazuyuki Hirokawa (who suddenly passed away in 2012) as episode directors, the level of the work improved. The production of Voltes at Studio 2 also wrapped up early, so Mr. Nobuyoshi Sasakado, a key animator famous for his fast work, assisted us by taking charge of the final episode. Surprisingly, he finished it before the previously ordered episodes were done, giving rise to the legend that he helped out with the previous few episodes as well.

Super Robot Generation Sunrise 1977~1987

The broadcast itself ended after half a year, just as originally planned. But the audience ratings and toy sales were both favorable, so episode 20, "Eve of the Decisive Battle," was hastily produced as an extra insert episode. The animation was done by the staff of the followup program The Unchallengeable Daitarn 3.

Despite its short broadcast run, Zambot 3 delivered satisfactory results in terms of both TV ratings and toy sales, cementing the alliance of Nippon Sunrise, Nagoya TV, and Clover—not to mention giving Yoshiyuki Tomino the redemption he sought after Reideen, and launching a series of Tomino-directed robot shows that would ultimately lead to Mobile Suit Gundam.

Eiji Yamaura — Zambot 3 / Daitarn 3 Chronicle

From the outset, we'd decided that Zambot 3 would run a total of 26 episodes. This was to maintain a good balance with the toys. With the broadcast starting in October, at first we'd be releasing merchandise in the low-cost range, followed by the high-priced main products for Christmas and the New Year. Ultimately, because of the timing, we had a year's worth of results in just six months. Because the toys sold so well, they let us do the following Daitarn 3 for a full year.

In the following years, there was even some consideration of compiling Zambot 3 into a feature film, although it's unclear how close this ever came to reality.

Yoshiyuki Tomino — Zambot 3 DVD Memorial Box

I came up with a plan to create a main storyline that would seem like a single narrative if we made a two-hour film version of Zambot 3. As I was making them, I was very conscious of which episodes would be omitted from the film version, and which would be included in the main storyline. So I figured I'd be able to compile it into about two hours.

It's different from a modern action movie. Thirty years ago, I was envisioning a structure where they showed show up one by one and then built up to a climax. I'd include the human bomb plotline in the middle of the story, and then show what happens to the Jin family when the King Bial ultimately breaks apart.

—So you were thinking of doing a film version?

Since it had been decided it would run two cours, I thought it would be easier to make if I created that sort of plan. It was just a question of how to make it. I was confident I'd done a good job in terms of the structure, so at one point, around the time of Daitarn 3, I tried connecting it all up. If I followed the flow of only the necessary episodes, it ended up being about three hours, so I knew I could turn it into a two-hour film. Trying that kind of task, I also realized it made the job more interesting when the series had a fixed overall structure.

—Was there any realistic discussion of doing a film?

None at all. What's really disappointing is that I originally wanted it to be an example, showing that you could make a movie even out of a story like Zambot 3 if you tried in earnest. But nobody took any notice of it.

The World of Tomino Yoshiyuki

The theatrical version of Zambot 3 would have been a summary of the TV version's story, but it ultimately never came to pass. As well as a synopsis, a recording script was also prepared, so it appears that Sunrise itself was aiming to release this. The recording script in Tomino's possession is dated June 1980, so perhaps the plan was to release this after the end of Mobile Suit Gundam's TV broadcast run?

"Zambot 3" feature film synopsis and recording script. According to "The World of Tomino Yoshiyuki" exhibition catalog, the synopsis dates from 1978, and the script is dated June 1980.

The final episode of Super Machine Zambot 3 aired on March 25, 1978. The followup series Daitarn 3 didn't premiere until June 3, and the two-month gap was filled with reruns of selected Zambot 3 episodes.

The following year followed roughly the same pattern, as Nippon Sunrise produced another original robot show and another subcontracted work for Toei. Perhaps the most notable development was the appearance of some creators who would go on to play key roles in the company's future works.

闘将ダイモス

闘将ダイモス| TV BROADCAST | |||||

| TV Asahi • Saturday 6:00-6:30 PM April 1, 1978 to January 27, 1979 (44 episodes) |

|||||

| MAIN CREDITS | Planning | Kanetake Ochiai (TV Asahi) Takashi Iijima (Toei) Takeyuki Suzuki (Toei) |

Original story | Saburo Yatsude | |

| Planning cooperation | Momiji Akino (Y&K) | ||||

| Music | Shunsuke Kikuchi | Original character design | Yuki Hijiri | ||

| Mechanics setting | Studio Nue | Animation character design | Akihiro Kanayama | ||

| Chief director (総監督) |

Tadao Nagahama | Production cooperation | Tohokushinsha Nippon Sunrise |

||

| Production | TV Asahi, Toei, Toei Advertising | ||||

| ADDITIONAL CREDITS | |||||

| Art | Takashi Miyano | Setting assistant | Mitsuko Kase | ||

| Animation manager (作画制作) |

Tadashi Yahata | Production supervisor (制作担当) |

Masami Iwasaki | ||

The third in director Tadao Nagahama's Romantic Robo series, Fighting General Daimos retained many of Voltes V's creators and staff, and Sunrise Studio 2 remained the production site. The "Sunrise Anime Super Data File" describes it as follows:

The Baamians, who have lost their home planet in a disaster, want to migrate to Earth. But the Baamian representative, Marshal Leon, is assassinated in the middle of negotiations with the Earth side. Convinced that this was a plot by the people of Earth, Leon's son Richter leads his army in an attack on Earth. Kazuya Ryuzaki confronts Richter in the Daimos, a transforming robot made by Doctor Izumi...

The third of the Nagahama robot shows. Rather than a formula in which the Earth side defeated the alien invaders, it told a story in which they searched for a path to coexistence even as they battled. Richter's younger sister Erika, caught up in the fighting, was saved by Kazuya and the two fell in love, a tragic romance which became the central axis of the work. Yutaka Izubuchi also made his official debut here as a guest mecha designer.

One significant addition to the creative team was Toei producer Takeyuki Suzuki, whose previous experience was in live-action hero shows such as Akumaizer 3. Suzuki brought in a professional fight choreographer, Kazutoshi Takahashi of the Oono Kenyuukai group, to provide stage combat reference for the animation staff.

Takeyuki Suzuki — Combattler V & Voltes V & Daimos & Daltanious Chronicle

At the time, live-action works were in a dramatic decline, and anime was booming, so in that situation I had no choice but to do anime works too.

—And so you joined Daimos. Was that a difficult adjustment?

Actually, since I'd been working in the live-action field, at first I honestly wondered why they were making me do anime. (wry laughter) But as I was doing it, it became really interesting. There were so many things that you couldn't do in live action.

The biggest thing I learned was my own way of making a giant robot show enjoyable. I wasn't interested in doing things the usual way, so I called in a fight choreographer. I showed his moves (stage combat) to the staff at Nippon Sunrise (now Sunrise), recorded them on video, and asked them to work with that.

—That's amazing.

They were all quite surprised, and asked "Why do we have a fight choreographer?" But I thought it was essential if we were doing action. We used to have fight choreographers come over to Toei Doga (now Toei Animation) from the film studios, too. After all, there's always a gap between the moves you come up with in your head and the real thing. And while they were watching that video, everyone started saying "Oh, interesting!" and tracing the movements as they drew.

Takeyuki Suzuki — A Man Who Keeps on Chasing Dreams

We'd adopted a method in which, rather than controlling the Daimos with joysticks, Kazuya used tube-shaped "tracers" attached to the upper half of his body to transmit his karate moves directly to the Daimos. This enabled us to show some impressive stage combat, but unfortunately with anime there are budget and schedule constraints, so they told us we couldn't draw new cuts for each episode's fighting scenes. For the most part, we had to recycle existing bank film. If it had been live action, we could just have shot new footage each episode, but I learned that wasn't the case with anime.

As with Com-Battler V and Voltes V, the main robot was designed by Katsushi Murakami of Popy, with Studio Nue providing supplemental setting and mecha designs. A young mechanical designer named Shoji Kawamori, who had just started working part-time at Studio Nue, made his anime debut on this series.

Takeyuki Suzuki — A Man Who Keeps on Chasing Dreams

As we were proceeding with the animation based on the completed design sheets, Mr. Murakami came to me at the very last moment and said "Mr. Suzuki, I have a favor to ask." I asked what he wanted, and he said he'd like to add green to some parts of the Daimos's body.

I swiftly refused, saying "Even if you want to change the colors, it's too late now. We're already sending it to photography." But Mr. Murakami wouldn't budge, saying "Please do something about it." Though there was barely any time left, I had no choice but to listen to him, so we redid the colors on the cels and shot them all over again. Somehow we pulled it off without incident, and Fighting General Daimos successfully aired on schedule.

When I met Mr. Murakami a few months later, he actually said "Maybe the previous colors were better after all." At the time, I couldn't believe it after all the effort that had gone into fixing them. But I suppose an outstanding creator can perceive differences of nuance even in trivial details that a layman would overlook, and design even when they're sometimes uncertain.

Shoji Kawamori — Kawamori Shoji Design Works

I was about 18 when I started working on Fighting General Daimos, and still a student. I began helping Mr. Kazutaka Miyatake around the third cours, and I was really happy to see my own designs animated on TV for the first time. When I was designing, though, they told me "Don't use anything but circles, triangles, and squares," and it put me in such a difficult position that I almost couldn't draw anything at all. It's a harsh memory. (laughs)

☆ Click the image thumbnails below to see them at full size! ☆

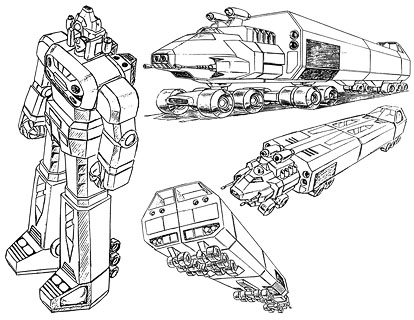

Left: Final Daimos setting art.

Right: Supplemental Daimos and Tranzer setting art by Studio Nue.

Daimos internal cutaway diagram, special attacks, and cockpit setting by Studio Nue.

Daimovick, Gullver FXII, and Baamian spacecraft setting by Studio Nue.

Daimovick design is based on a rough draft by Katsushi Murakami.

The series premiered on April 1, 1978, one week after the final episode of Voltes V. With its conclusion in January of the following year, the time slot it had inherited from Com-Battler V and Voltes V was turned over to the live-action special effects show Battle Fever J, the third in the live-action "Super Sentai" series which later became the basis for America's Power Rangers. This would mark the end of the Romantic Robo trilogy.

Scenes from Daimos's opening credits.

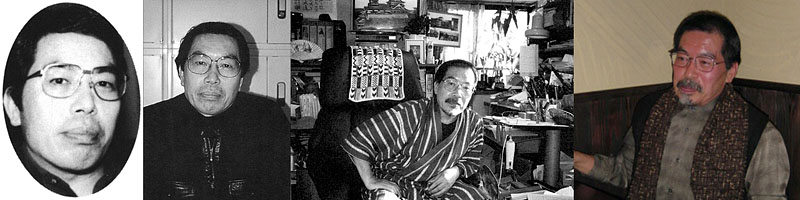

From the standpoint of Sunrise history, Daimos is perhaps most notable as the debut of multitalented mecha, costume, and creature designer Yutaka Izubuchi.

Left to right: Yutaka Izubuchi in 1983, 1986, 2000, 2004, and 2025.

Like many other young creators who began working with Sunrise in the late seventies, Izubuchi was recruited by the famously fan-friendly Nagahama. Though his name didn't appear in the series credits, enemy mecha based on Izubuchi's rough sketches began appearing in the middle of the second cours.

Yutaka Izubuchi — Yutaka Izubuchi Mechanical Design Works

It originally started because I had the opportunity to visit the studio a few times when Sunrise was working on Voltes V. I was still in high school then... At the time, I was involved in SF doujin activities with a friend, and I had an idle fantasy of making something like that as an independently produced anime.

Then, maybe during my second visit, I showed the director Mr. (Tadao) Nagahama a bunch of drawings I'd done (for my own anime). This around the time when Voltes had ended and Daimos was approaching its midpoint, and it seemed they were running out of ideas for enemies. So Mr. Nagahama asked me, an amateur who'd come on a sightseeing trip, whether I wanted to give it a try. That's how it all began. Thinking about it now, maybe that was reckless, or was it brave...? No, that was just Mr. Nagahama. (laughs)

—So you didn't want to become a designer from the beginning?

I've been doing it for a long time, so now I go by the title of mecha designer, but I think back then I wasn't conscious at all of wanting to become a designer. I wasn't fixated on working only in animation, either. I was interested in anime, but I originally thought of myself as someone in the special effects field.

When Mr. Nagahama asked me, I accepted with the feeling "If they're going to let someone like me do it..." In hindsight, I didn't have a clear vision, and I joined in assuming that I'd figure it out somehow. (laughs) I was just drawing roughs, so the fees they gave me were only like part-time wages. And since I joined in halfway through, my name didn't appear in the staff credits either. At that point, I never even considered making a living from this.

Yutaka Izubuchi's design work for Daimos was also inspirational for Takeyuki Suzuki, the Toei producer. When he returned to live-action work, Suzuki began applying the lessons he'd learned from anime to the "Super Sentai" series. His invitation to work on 1983's Kagaku Sentai Dynaman would be the beginning of Izubuchi's long career as a live-action costume and creature designer.

Takeyuki Suzuki — A Man Who Keeps on Chasing Dreams

At the time, I think Mr. Izubuchi was preparing to retake his college entrance exams, but I was surprised someone so young could draw such unique mecha designs. I felt that anime designs were more innovative than the live-action designs of the time, and I suspected this excellent design was one of the reasons for the anime boom. It was partly for that reason I got to know Mr. Izubuchi, and I was secretly determined to ask him to work with me when I eventually went back to producing live action.

Another distinctive feature of Mr. Nagahama's robot anime was the appearance of beautiful villains, such as Admiral Richter in this work. I realized these beautiful characters were popular with diehard fans, so I wanted to incorporate this element as well when I returned to live action.

Takeyuki Suzuki — Combattler V & Voltes V & Daimos & Daltanious Chronicle

At the time, anime works had a lot of beautiful characters. When I later returned to live-action works, I tried including these kinds of "beautiful" characters in things like Kagaku Sentai Dynaman (1983). For example, Prince Megiddo (Kenju Hayashi) and Princess Chimera (Mari Kono).

Though Daimos was well-received, the broadcast ended ahead of schedule because the TV station was eager to turn the time slot over to Battle Fever J. Director Tadao Nagahama hastily wrote a closing message to address the abrupt end of the story.

Takeyuki Suzuki — A Man Who Keeps on Chasing Dreams