Production Reference:

Production Reference:|

|

Translator's Note: The quarterly magazine Great Mechanics, published by Futabasha, is devoted to in-depth coverage of current and past mecha anime. It frequently publishes exclusive interviews and behind-the-scenes features, including Coelacanth Kazama's True Stories: Showa Robot Anime Production Site Report, a series of reminiscences about the production of classic robot anime by Yoshie Kawahara, formerly of the Sunrise planning office and now a freelance writer. Here, I've translated selected installments from the series. The following text is copyright © Futabasha. |

Translator's Note: The text below is the standard introduction repeated at the start of each of Kawahara's columns.

Have you heard of someone called Hiroshi Kazama, or someone named Yoshie Kawahara? From the late 1970s to the mid-1980s, Kazama was credited mainly in setting-related roles on many of Sunrise's robot anime, from Robot King Daioja to Aura Battler Dunbine. Kawahara, meanwhile, was a scriptwriter on Heavy Metal L-Gaim and the author of the Yoroiden Samurai Troopers novelization. In fact, these two are the same person, one of the few female core staff members at (then) Nippon Sunrise, which produced many robot-show masterpieces. In this series, Ms. Kawahara tells us about her memories of the past. What was the robot anime production site of 30 years ago like?

Text: Yoshie Kawahara, AKA Coelacanth Kazama

Profile: Yoshie Kawahara • Born in Tokyo's Suginami Ward. In senior high school, Kawahara joined Sunrise Studio (Ltd.) as a miscellaneous part-time job (1975). After graduation, she automatically became a Sunrise contract staff worker. At first she was also active as an anime fan, but soon moved on from this due to the demands of her busy workplace. After this, Kawahara accumulated experience of all kinds, driven by the needs of her workplace duties. In 1980, she was officially assigned to the planning office. Temporarily seconded from the planning office, she became the first female "setting manager," and from 1984 onwards she worked full-time in planning. After her contract ended in 1989, she began working as a freelance writer.

It's not particularly useful, but the coelacanth is an ancient fish that has survived since prehistoric times.

That's exactly what I am in relation to the current Sunrise. Even now, they occasionally reel me in, but I guess I'm pretty old and not all that tasty. Nonetheless, I'm pretty sure there's nobody else left who's been swimming in the waters of Sunrise as long as I have.

As I begin this series, by way of a preamble, I need to explain my own relationship to animation. Recounting some of my personal history will also help to convey the background of that era. So please bear with me.

My first glimpse of the production side of animation was probably when I was around 9 years old. A childhood friend showed me a "cel." It was from Wonder 3, produced by the old Mushi Production, and it showed the protagonist's brother Koichi Hoshi from the waist up. My friend lifted up the overlaid cel sheets, laughing "If you do this, he's bald." In hindsight, it must have been a cut in which his hair was waving. The bald Koichi was the A cel, and his hair was the B cel. That was the moment in which I realized how TV "manga" was made.

The broadcasting of TV anime began with Mighty Atom, during Japan's period of rapid growth in the second half of the Showa era. My own generation grew up alongside it. There was Atom when I was in kindergarten, then Tetsujin 28 and Eightman in my first year of elementary school. After that, "TV manga" flooded prime time as if a dam had burst, and many of my generation experienced a desperate struggle to retain control of the TV channel.

Personally, around the middle of elementary school, I became devoted to manga magazines and started following the path of an aspiring manga artist. But just as I entered high school, Devilman and Mazinger Z began airing in parallel to their magazine serialization.

Many of the like-minded friends I made in high school were diehard anime fans who'd always been watching TV anime. With the fuss surrounding the collapse of the old Mushi Pro, I found myself drawn back into contact with anime, for example by being lured into attending screenings of Mushi Pro works organized by volunteers. That's when Space Battleship Yamato came along.

Even though I'm female, ever since I was young, for some reason I was never good at girls' games and my interests didn't align with other girls my age. The programs I watched were things like Space Patrol Hopper, Combat, and Captain Scarlet, which was pretty strange for a girl back then.

So it was inevitable that someone like me would get hooked on Yamato, which appeared under the banner of Mr. Leiji Matsumoto, who I knew as a manga artist specializing in mecha and science fiction worlds. Together with the information that "it seems there are things in anime called setting materials" and "there's a studio in such-and-such a place that does the drawing," this started making me interested in so-called materials and in fan club activities as well. And then I encountered Reideen the Brave.

Kawahara watches Space Battleship Yamato on a black-and-white TV.

Putting aside the question of why Reideen for the time being, some people may think it strange that I was credited with the male name "Hiroshi Kazama." The name "Hiroshi Kazama" is one I'd actually been using since middle school as my manga pen name. As I mentioned above, my tastes were pretty male-oriented, and my behavior was far from ladylike. That's why I went with a male pen name. When I visited Sunrise, of course I was going by this name, and since the people around me called me "Kazama-kun" and "Hiro-kun," the same thing quite naturally happened around the studio as well.

When I eventually appeared in the end credits, my boss in the planning office listed me as Hiroshi Kazama in the staff list. He said "Kazama is fine, right? Everyone will know who that is. Anyway, a female name would stand out."

This feeling that "a female name would stand out" might seem peculiar now. But there were no women involved in production at the time, and in the industry as a whole, most of the women were finishing staff. So "a woman in production" would have seemed strange. And though I personally didn't feel strongly about it, when it came to "robot and mecha shows" like those of Sunrise, it appeared the outside world had the fixed idea "What would a girl know about robots?" (I'd come to realize this later on when I was focusing on planning work.) Thus, it was actually thoughtful of my boss to decide that in many ways it would be easier to use a male name.

After that, I was called "Kazama" both in the credits and within the company. But when I was writing scripts for Heavy Metal L-Gaim, the producer in charge asked, "Isn't it bad to have a name in the credits that's always appeared as a production staffer?" So we decided to use my real name, which was completely unknown to people in the industry. After that I did all my writing work as "Yoshie Kawahara," and that's continued to the present day.

This didn't seem particularly strange to me at the time, but looking back on it now, all I can think is that in many ways I was working in a "gap between eras."

Let's get back to the story.

I recall the information that "They're making Reideen somewhere near your route to school" came my way about one month after the start of broadcast, in May 1975. This led to my knocking on the door of "Sunrise Studio Ltd.," where everything began.

Of course, I'd first seen Reideen the Brave when it aired on TV. I might be so bold as to say that it felt like my own drawings had come to life. I'd never seen such beautiful robots and characters in anime before. So I wanted to see the model sheets, no matter what.

A dark and narrow staircase led up to the second floor above a coffee shop. I started to worry whether this was really the place, but on the wall there was a large-format cel from episode 1 with an attached background, showing the Reideen with its limbs entangled by a Drome, and there was a promotional poster on the entrance door. So I was confident I wasn't mistaken.

Behind the door was a one-room floor with the kind of plastic tile flooring you often saw back then. There were ranks of production desks with various things piled on top of them, and in the back were cut bags crammed into steel shelves. Handwritten schedule charts and broadcast lists were posted on the partition wall in the middle.

The moment I saw this "Studio 1," with its piles of cut bags stuffed with the cels that seemed like such treasures to us, I felt like Ali Baba when he said "Open sesame!" Nonetheless, I remained deadly serious as I was vaguely aware that I ought to be polite, and I was initially allowed in as "a tour for an anime research club." But I was so completely ecstatic that I don't remember any of the details. And somehow it was Director Yoshiyuki Tomino, who happened to be there in the studio, who ended up escorting this student.

Next time, I'll talk about the relationship at the time between Sunrise and Tohokushinsha, as well as the Reideen production site.

"What?! A high-school student? Watching something like Reideen?"

That was the first thing Director Tomino said. As a high-schooler who'd taken an interest in TV animation with the broadcast of Space Battleship Yamato, I'd then encountered Reideen the Brave, and in May 1975 I paid my first visit to this small production studio on the second floor above a coffee shop, under the pretext of an interview tour for an anime research club.

Nowadays there's nothing strange about adults being anime fans, but at the time, the idea that a high-schooler might be watching anime was unusual in itself. (Though in fact, the surprising thing was that we were all watching it.) For one to show up at the production site was definitely an unusual development.

"What could be interesting about Reideen at your age?" At the point when he asked me that, I still had no idea who he was. Even though I figured I should probably try to play it cool, I babbled "It's just fun, it's so cool, I love, love, love it!"

Mr. Tomino, who at that point was sporting a beard and still had glossy black hair, stared in amazement as he listened to the feverish ranting of this young newbie. "Eh, really? Is that so?"

As I briefly mentioned last time, it's said that Japanese robot anime has continued from 1963's Mighty Atom up until today, but I feel a little differently. Ever since Atom, Tetsujin, and Eightman, robots themselves had constantly appeared in children's programs, but I don't think there were any works that could be called "robot anime" until 1972's Mazinger Z. Sunrise, the company I joined, didn't come into the world doing robot anime either.

Sunrise was launched in 1972 by seven former Mushi Production employees, mainly from the production department. With funding from Tohokushinsha, they started a pair of companies called "Soeisha Inc." and "Sunrise Studio Ltd." At the time, Tohokushinsha was a company that imported and sold Western movies and so forth. Among these works was Thunderbirds, and since Tohokushinsha had achieved success by commercializing the mecha that appeared in it, the company now had plans to start its own rights business. Thus it needed to develop programs in-house.

Soeisha, as a planning and production company established to meet this necessity, could be called "Tohkushinsha's anime production department." Though the company participated in the production of Hazedon while it was still in the middle of starting up, 0-Tester was the work that fully embodied Tohokushinsha's aims. Sunrise Studio was the work site responsible for the actual production of these two works. In other words, until it ultimately escaped from its role as a Tohokushinsha subsidiary in 1977, becoming "Nippon Sunrise Inc.," Sunrise was split into two companies.

While the other girls swoon over Reideen's handsome hero, Kahawara falls for the beautiful robot.

Sunrise Studio's Studio 1, the location where Sunrise Studio was first established, was also the production site for Reideen the Brave. This was produced by Soeisha, while Tohokushinsha held the rights. The aforementioned Hazedon and 0-Tester were made here as well. By the time of Reideen, a Studio 2 had also been launched to produce Star of La Seine, and preparations for the production of Wanpaku Omukashi Kum Kum were under way at Studio 3. Both these studios were within about two minutes' walk. (Unfortunately, I never visited them during these productions.)

However, as a high-school student who'd brazenly plunged into fandom, and who remembered only that the name "Soeisha" appeared in 0-Tester, which I'd occasionally watched, I had no idea that such grown-up matters had culminated on the second floor above a little coffee shop in Kami-Igusa's Suginami Ward.

Eventually, as if he'd seen through to my real intentions, Director Tomino asked "You want some cels?" He gave me a few from the cut shelf in the back as a present. Though I can't tell you the details, honestly it was a situation that made me wonder if it was really okay. But in those days, after they were done with them, the cels were actually considered industrial waste, and they'd have to pay a fee to send them to a landfill at Tokyo Bay. I guess that's why he had surprisingly little hesitation about giving them away. I heard from him years later that he was rather amazed by my visit, and it may have been a hint at a new direction.

After this, a production assistant showed me the key frames and in-between animation inside a cut bag, and since the art director had a desk in the studio, I was also able to see where the backgrounds were painted. I really got a lot of quality time. The episode they were pre-shooting was episode 9, "Terror! Mammo's Freezing Operation." I know this because a 240 frame-size cel of the God Bird swooping down from the sky towards the enemy fossil beast Mammo was spread out on the production desk. Even now, I still remember the emotional impact of realizing "It's that cel!!" when it was later broadcast.

We'd also talked about putting out a Reideen special issue of the research club newsletter, so about two weeks later I visited again. This time, a production assistant who happened to be there said "You draw manga, right? Then you can draw straight lines." They asked me to do a tracing (in other words, dōga) for a still image. (1) They also asked "Want to try painting a cel?" and showed me to a tracing desk.

As a naive student who was there because I loved the show, I couldn't help being delighted. I sat at the tracing desk as I was told, picked up a pencil and a brush, and in short I was gently coaxed into helping out.

The staff at a Sunrise studio are the people who basically "make" the work, but the actual drawing and coloring is outsourced. This is a system quite similar to a magazine's editorial department. There, the publishing company's editors commission manga artists and novelists to create the manga and novels they publish. Then the editorial department collects these, puts them into book format, and sends them from the printer to the bookbinder.

A Sunrise production studio is roughly the same, so to untrained eyes, it's hard to tell what they're actually doing. At any rate, it was full of young men constantly rushing in and out carrying "octavo format B4 size" paper bags (cut bags). Nonetheless, I took them at their word when they said "Come again," and during my multiple visits I naturally came to learn about tasks such as finishing (coloring the cels) and simple dōga work. Mr. Toshihisa Tojo, who died at a young age, was responsible for the background art, and he even taught me how to draw backgrounds when he had free time.

It was a young company, and even Director Tomino was only in his early thirties. The schedule must have been really tough, but the atmosphere was always bright. The lively "big brothers" among the production assistants loved to play around in ways that made you fall down laughing, like when they'd face off against opponents armed with brushes and rulers, putting their arm through the lid of a plastic bucket and yelling "God Block!" (2)

Unlike today, however, most of them hadn't joined the company with the initial goal of doing animation production. Instead, they were working as production assistants because they loved cars and loved driving. In an era with no Internet or data transmission, key frames and in-betweens were physical objects drawn on paper. The production assistants weren't just responsible for schedule management on their assigned episodes, but for "transport" as well, so they got to spend pretty much the whole day in a car.

But for exactly that reason, the staff at least weren't a bunch of "maniacs." The job was "making pictures for children's programs," so however much Space Battleship Yamato had revealed the existence of older viewers, that was something only the fans were aware of. As far as the anime industry itself was concerned, their audience consisted of little kids and sponsors such as toymakers and candy companies.

(1) The Japanese term 動画 (dōga), often translated as "in-betweening," literally means "animation." In the animation process, the douga stag includes both in-betweening and cleanup of the key frames, and it seems Kawahara is being asked to do the latter task here.

(2) This is actually a plausible imitation of the Reideen's trademark shield.

One day, a man wearing thick glasses ordered me a soft-serve ice cream from the coffee shop downstairs. Having a coffee shop below us was very convenient, and we could even get coffee delivered during meetings. When I gratefully accepted it, he said "Here, you'll understand this if you're watching the program. Could you pick out some cuts that you've seen a lot from these shelves? Otherwise, just combine good scenes with backgrounds to make pictures."

He said this with a smile, pointing to the mountain of cut bags crammed into the steel shelves behind him. I was to make selections for the so-called "bank system," and create promotional cels to be given to TV stations and so forth. Thus, on that day, I was "hired" with an ice cream. The man with the glasses who had greeted me was Mr. Masao Iizuka, the planning office desk chief, who would later become my boss.

The bank system was a method for storing cuts that could be reused in later episodes, in order to at least slightly reduce the number of new drawings required (thus saving time and expense). Apparently Mr. Osamu Tezuka came up with this during the production of Mighty Atom, and at Mushi Pro it had been Mr. Iizuka's job to manage and store everything created during the production of their works, including this bank system.

"If you see anything you think could be used again," he said, "set it aside." So if I picked out a cut thinking "Hmm, this drawing of it looking over its shoulder is nice," I'd classify it by recording the contents on the bag, like "Reideen looks over its right shoulder." (This bank system was refined over the years, and later they even created a job position for a dedica†ed "bank clerk.")

Eventually, he told me "Please open a bank account so we can deposit your part-time wages there. And can you stop by after school on Saturdays from now on?" And that's how a mere "intruding student" became a part-time employee.

The jobs I was given varied from time to time. So sometimes I'd be organizing materials, and sorting and discarding the used cels that were once considered so precious. Sometimes I'd be finishing (coloring) cels, helping with simple drawing tasks, and doing other odd jobs that came up in the production process. Since they were busy that enough to need help from someone like me, nobody taught me anything, and I either taught myself or watched and imitated other people.

The only woman in the studio was working as a production secretary. But even though I was a female high-school student, I always wore jeans back then and was far from girly on the inside. Maybe that's why I was so easily accepted by my colleagues, and looking back, I really appreciate that.

This is a little out of order, but around that time I stopped seeing Director Tomino, who I'd initially been working with. I gather the reason was that Reideen the Brave had been planned with the themes of "occult" and "mystery" and "ESP," which were really popular at the time, but they decided to change course due to the preferences of the TV station, and so they replaced the series director and producer as well. I had no way of knowing this at the time, and I only heard about it from the late Tadao Nagahama, the director of the second half.

"You should ask this person about Reideen from now on," said Mr. Iizuka, introducing me to Director Nagahama, a little "uncle" with a goatee beard.

At the time, he was 42 years old. He'd started out with a puppet theater company, and directed old Tokyo Movie series like New Obake no Q-Tarō, Chingō Muchabee, and Star of the Giants. But it seems he'd been appointed because his ability had been recognized on Star of the Giants, which became a particularly huge hit. Back then, Director Tomino gave the impression of being shy and serious, but Director Nagahama was very sociable and his attitude was "Fans welcome!" Like most people, he was initially surprised that a high-schooler would be a fan of "robot manga," and it seemed like he was interviewing me instead of the other way around.

"So that's how you see it. Please be sure to come and tell me your thoughts from now on."

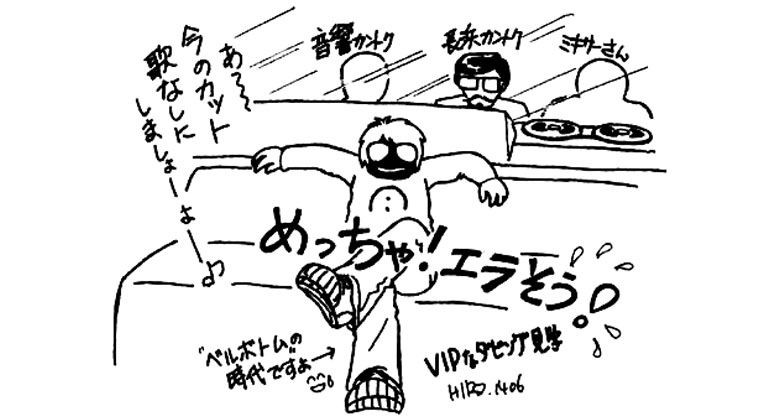

This was like a VIP ticket to come in and out of the studio. And what's more, I was invited to come and watch the upcoming dubbing (recording of sound effects and background music) of episode 27, "Sharkin's Devilish Battle," at Tohokushinsha in Akasaka. This was the first time in my life I'd ever visited a recording studio, but I was sitting behind the sound director alongside the director himself. It was a first-class experience being there as they chose sound effects and background music to accompany the images playing on the screen on the other side of the glass. (1)

In episode 27, the enemy Prince Sharkin is defeated in battle by the Reideen and dies by his own sword. Director Nagahama chose an audio arrangement using hand drums, which was unusual at the time, for the background music during the battle.

Kawahara enjoys a VIP experience at the Reideen recording studio. Director Nagahama is visible behind the glass, next to the sound director.

"In the first place, something that's not interesting to adults won't be interesting to kids either. Personally, I think the fact it's for kids is exactly why we have to take it seriously. Children watch drama and understand its contents more fully than adults think. If we make fools of them, then the kids will make fools of the people making it."

That was a favorite credo of the dramatist Tadao Nagahama. It's just my own impression, but in his heart, the Director Tomino I know is like that too. However, their expressive styles seemed like complete opposites. Director Nagahama's highly exaggerated emotional expression was a technique that Director Tomino wasn't very good at back then.

Even more than a contrast in personality, I think there was a difference in taste between Director Nagahama, whose background was in theater, and Director Tomino, who wanted to make live-action films. Or to put it another way, perhaps there was a difference between the still-youthful Yoshiyuki Tomino, and Tadao Nagahama who was reaching veteran status.

I was also a novice at the time, and I was at an age where I tended to look at things cynically. So I definitely had some resistance to the complete showiness of the Nagahama style, but I felt his creative approach was the right one. It seemed Director Nagahama understood that as well, and he never once said anything critical about Director Tomino. As for the aforementioned change of director, he defended him by saying "I feel sorry for Mr. Tomino. It was the TV station that told him to use occult and ESP themes, so it wasn't his fault."

In any era, when it comes to so-called "grown-up matters," these matters are resolved in some visible form. But there's no question it was Director Nagahama's sense of justice and chivalry that led him to say frankly that the way they were resolved was unfair, and ultimately he turned the program Reideen the Brave back in the direction of a "mystery show," even though it wasn't the way Director Tomino had originally planned it.

It was truly a privilege that he brought me along to the post-recording and dubbing of the final three episodes. But when Director Nagahama turned to look at me sitting behind him, and asked me each time what I thought, I'm utterly mortified that even though I was a total novice, in my youthful enthusiasm I gave grown-up answers like "Wouldn't it build more tension if there was no BGM here?" But now, after all my experiences, I can only express my gratitude to Director Nagahama for going so far to incorporate a fan's sensibilities into his film.

(1) In her illustration, Kawahara depicts herself sitting in front of a window with Nagahama and the sound director behind her. But that doesn't seem to match what the Japanese text describes, so maybe the drawing is an exaggeration for comic effect.

Well, what kind of people did I know at Sunrise back then?

As I briefly explained in the first installment, Sunrise Studio Ltd. was the actual production site for Soeisha Inc., which was something like Tohokushinsha's anime division. I was going in to Studio 1, on the second floor of a coffee shop in Kami-Igusa, Suginami Ward, where the Reideen the Brave production crew was located.

The producer Mr. Yoshinori Kishimoto was the president of Sunrise Studio, and became the first president of Nippon Sunrise Inc. when it later went independent. Thus he was often at the main office, which was also in Kami-Igusa but at a different location, and we seldom saw him at the production site. It was Mr. Yasuo Shibue, who later served as producer on Mobile Suit Gundam, who actually looked after things like the production schedule.

The role of series director was passed from Mr. Tomino to Mr. Nagahama. Mr. Nagahama had a desk there, of course, but he was often out, so I took the opportunity to talk to him when we held preview screenings in the studio. The four or five production assistants were all youngsters in their twenties, and most of them left the industry some time ago, so I won't introduce them here. But among them was Mr. Toru Hasegawa, who would later serve as producer on Space Runaway Ideon and Armored Trooper Votoms.

I already introduced Mr. Masao Iizuka, who would later be my boss, in the previous issue. He was in charge of things like setting and script management, copyrights, and publicity. The late Mr. Toshihisa Tojo, who would go on to found the background studio Art Take One and also worked on Cyborg 009 (1979), was responsible for background art. He also had his own desk, where he worked on art boards and so forth. The only woman was Ms. Sanae Takekawa, the production secretary. Their periods of employment weren't completely aligned with each other, but those were more or less the permanent members.

As the production entered its second half, Director Takao Yotsuji of Science Adventure Command Tansar 5, which was covered in a special feature in the previous issue of this magazine, was at the production site more regularly in a role like that of a script management assistant (his job description then was a little different from what it would be now). He shared behind-the-scenes stories with me, like how the giant beasts that appeared in Reideen were actually named after his favorite rock-and-roll bands... Even now, he's still like a big brother to me.

Meanwhile, the scriptwriters, episode directors, animation staff, and so forth weren't permanent staff, but only showed up as needed. For example, there was the color coordinator Mr. Hiroshi Hasegawa, who founded the independent Studio Deen and is now the president of Studio God Bird. Even now, it seems he's still proud of having done the color coordination on Reideen, and his affection for it is clear from the names of his companies.

Among the episode directors were the late Mr. Takeyuki Kanda, who directed Round Vernian Vifam and Mobile Suit Gundam: The 08th MS Team, Mr. Yasumi Mikamoto, who also worked on Space Battleship Yamato and Lupin III, Mr. Kazufumi Nomura who also directed episodes of Yamato, and so on and so forth. They were all freelancers under series contracts, and they only came in to do things like "pre-shooting" work and checking the film. So they didn't have their own individual desks in the cramped studio, and used a couple of shared desks instead.

Speaking of film, there was also Mr. Tomoaki Tsurubuchi of Tsurubuchi Films (now Tsurubuchi Editing). He learned his high-level techniques for changing the impression of movement and scenery simply by cutting and reconnecting one or two frames, in the filming of TV anime shot at 24 frames per second, working alongside Director Tomino.

As the production of Reideen was nearing its end, Mr. Haruka Takachiho of Studio Nue started showing up more frequently. Nue and Sunrise had been working together on things like science fiction setting ever since the planning of the previous 0-Tester, and on Reideen Nue was responsible for power-up ideas and setting design. During the planning work for the following Super Electromagnetic Robo Com-Battler V, he'd visit the company with design drawings for all the mecha setting other than the robot itself. One day, I happened to see a design rough for the command room of the heroes' base, the Nanbara Connection, and I unthinkingly commented that it looked like the bridge of the Yamato. He said "Don't all great things have similar designs?" and I remember we had a good laugh together.

Around the same time, a female college student who'd visited on a field trip a few months after me started working part-time as a cel organizer. And Ms. Mitsuko Kase, who loved Reideen as much as I did, came in as an animation assistant. At the time, she was a student at an animation school, and she later became Sunrise's first female director. As one of my few "contemporaries," Ms. Kase is still a good friend, but no matter how much she's accomplished she always says "I'm your junior by half a year!" (laughs)

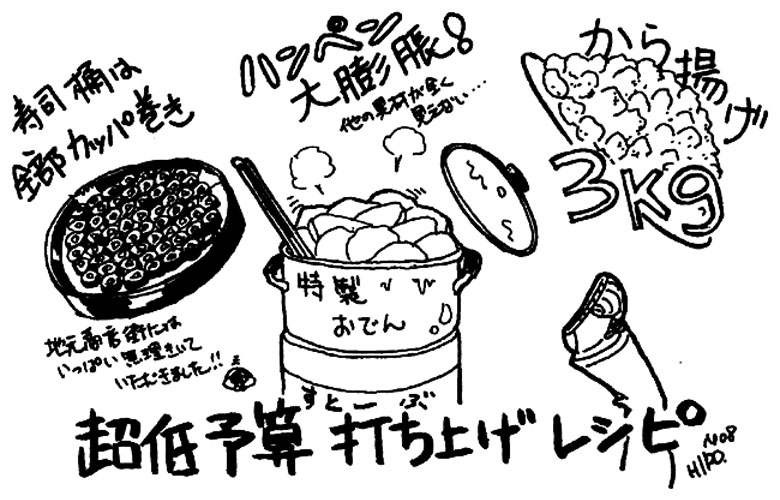

Some of the ingredients of a Sunrise wrap party—kappa maki, deep-fried karaage, and a giant oden pot filled with hanpen.

I'd be so bold as to say that people in the anime industry in the Showa era were generally broke. The only ones who kept regular working hours of 10:00 AM to 6:00 PM were the accounting staff. In practical terms, our work hours were "until you finish what you have to get done today." But since the people at the production site weren't employees, we didn't get overtime pay, and our salary didn't change however many hours we worked.

In exchange, though, we had some freedom and even a certain degree of leniency we could exploit at our own risk. For example, there was a small sink and gas range in the studio, where we could boil ramen, fry vegetables, and sometimes even grill fish the staff had received from their hometowns (which we'd have as appetizers with drinks). This sort of thing happened every day.

When the production of a work began or ended, it was customary to hold what are known as "launch" and "wrap" parties. The company didn't provide any funds for these, so usually we'd rely on pocket money from the site producer, the series director, or whoever to get beer and snacks from somewhere nearby so we could drink a toast. But this changed a little after women began joining in.

For example, the oden that started with us asking "Couldn't we make something cheap and filling?" Back then, we often switched from one work to another in early spring, so somebody brought a big aluminum pot from home and boiled the oden for half a day on one of the kerosene stoves used for indoor heating. Since there weren't any convenience stores in those days, we had to do everything from purchasing ingredients to seasoning it. This was extremely popular in a studio that had so many youngsters with hearty appetites. After that, it became a tradition to have oden at the studio's launch and wrap parties, and before we knew it we'd bought a dedicated pot.

Once someone kicked the staff out overnight because of the cockroaches and sprayed the place with insecticide, then came in the next morning and screamed at all the dead roaches lying upside-down on the floor. Another time, someone suddenly got curious and cleaned the ventilator fans, and the blades we'd always thought were ash-gray turned to have been red all along. (There were still a lot of smokers in those days.)

Since somebody was there 24 hours a day, it gave the place a lived-in feeling, and the production studio was like that up until roughly the mid-eighties. So the studio staff back then were truly "comrades eating from the same pot." Even when we switched to a new work, or were split up into different studios, we maintained a relationship where we'd help each other out when we were busy, and get in touch if we needed anything.

I'm already five installments into this series, but there's a very important person I haven't yet introduced. I'll be talking about this person for this whole column, so I appreciate your understanding.

When I started working part-time at Sunrise in the latter half of the 1970s, Mr. Iizuka told me to use a drawing desk in the furthest back corner of the studio, next to the wall, as my workbench. Though it was only about three steps away, it was separated from the other desks, with a sofa and table behind it that were used for meetings. Here I'd do various things such as painting cels, organizing cels, drawing, and so forth. But one day, I opened a drawer of this desk while I was looking for something.

Inside it were a couple of B4-size underlay-type card cases, with files of countless scraps of key art of the characters from 0-Tester. This was a work I'd naturally enjoyed watching, so I couldn't help taking these out and looking at them. All these key art drawings were wonderfully composed "nice faces," so I asked Mr. Iizuka if it would be okay for me to copy them. (1) He said it was fine, so I eagerly made my copies and put them back in the drawer.

Some time later, Mr. Nagahama suddenly said to me, "Kazama-kun, have you ever met Yasuhiko-chan?" I replied, "What's his family name?" Mr. Nagahama laughed. "Yasuhiko is his family name."

Oh! Up until then, I'd been under the impression that the name I'd seen in the TV credits was pronounced "Yoshikazu Abiko." In those days, it wasn't unusual in the studio for the staff to address each other by adding "-chan" to their first names. So I'd mistakenly assumed that "Yasuhiko-chan" must be a person named "Yasuhiko something." Then Mr. Iizuka chuckled, "The desk you're using belongs to Yasuhiko-chan."

What?! I'd been working at the desk of such an incredible person! That's why it was filled with all that key art of "nice faces."

Blushing, I confessed "No, I've never met him...!" He replied, "He's on the fifth floor of Sansan today, so why don't you come and see him?" It goes without saying that I jumped up right away.

I won't go into this now, but it's no exaggeration to say that Mr. Yasuhiko, who's famous as the character designer and animation director of Mobile Suit Gundam, is the person who created Sunrise's stylistic image. It's because of that style that I, too, fell for Reideen.

As for "Sansan," it was a legendary coffee shop near Sunrise (I'll talk about that on another occasion). Sansan was on the second floor, and at the time, the planning office was on the topmost fifth floor of the same building.

Though I don't remember who took me over there, somehow I have a vivid memory of the scene. It was a fine day at the start of winter. Warm sunlight was streaming into a tatami-floored room with shouji screens on the windows. There was a low table in the room before me. Stacks of books and papers were piled up all over the place, and there were toys lying around as well. In an irregular triangular room at the back there was another low table, and I had my first glimpse of "Yasuhiko-chan" as he sat before it, his pencil dashing across a sheet of storyboard paper.

At that point, he was probably drawing storyboards for episode 49 of Reideen the Brave. My memory is hazy, but I recall him listening pleasantly and patiently as as I told him all about my Reideen fan activities. He was also serving as original creator and animation director for Wanpaku Omukashi Kum Kum, which was being produced simultaneously at Studio 3, and he'd seldom come in to Studio 1 during my time there. Perhaps that work came to an end around this time, because he started showing his face around our studio afterwards.

Many stories of Mr. Yasuhiko's genius come to mind. First, although he didn't know anything about anime, when he joined (the former) Mushi Pro after seeing a job listing, his drawing ability was recognized after three days and he famously drew the ending images for the anime Wandering Sun.

Mr. Yasuhiko's working speed is amazing. Part of the animation director's job, is to check and correct the movement and style of the key frames drawn by the key animators, and he was blindingly fast at this. Sometimes it would only take him 30 seconds to check a cut. When he came to work, he'd start with a giant stack of cuts piled high on his desk, and with a "thwack, thwack" (the sound of a checked cut being tossed onto a shelf) he'd clear them all away in just one hour. Anyway, it was just so satisfying to watch.

Later, I was going to assist him with his serialized manga Arion, erasing lines and applying screen tone. When I called him the day before, he said he'd only finished three pages of rough sketches. But he told me to come over around noon the following day, and when I did, he'd finished 20 fully inked pages. I asked him if he'd stayed up all night, and he replied "There's no way I could do that. I went to bed at midnight." He also said the famous line (?) "I hear they give you a week for storyboards now? Back in our day, we used to draw those in an hour."

Meanwhile, he once happened to be passing by a bunch of young production assistants who were unable to pull on a chest expander and had completely given up. He easily pulled it taut, and then went on his way with a smile, saying "What, you can't pull something like that?" After that, the gossip around the studio was "Drawing ability is all about physical strength!"

In fact, Mr. (Yoshiyuki) Tomino once said "I could never get into a serious fight with Yasuhiko! With his superhuman strength, he'd just toss me out of the building (on the fourth floor)."

One day, this person said to me, "Kazama-kun, what should I do with this...?" With a complex expression, he showed me a design for a robot toy that was somehow hard to describe. Since it was purely a design drawing for a toy, it couldn't be turned into a model sheet for an animation hero mecha as it was, and Mr. Yasuhiko had been entrusted with designing it for anime use.

I understood from his expression that he was bewildered, but I couldn't help responding "What, with this?!" A few days later, Mr. Yasuhiko appeared in the studio. Grinning, he asked "How's this?" He took a piece of paper out of his favorite attache case and held it up before me. This was Super Electromagnetic Robo Com-Battler V. And that was the moment I realized he was truly "Yasuhiko the genius."

Later, on Robokko Beeton, it was my duty to pick up his drawings for the title backgrounds for each episode, and turn them into cels. I was a setting assistant on Super Machine Zambot 3, and he later nominated me to be the literature manager on Giant Gorg, so I've come to enjoy a rather privileged relationship with him.

Looking back, I think what made this possible was probably the fact that he knew I was always drawing manga. Mr. Yasuhiko also wanted to become a manga artist. Perhaps because of that, although my drawing ability couldn't compare to his, ever since we first met he'd freely show me his techniques and his brilliant working methods. "The lines will be livelier if you don't use a ruler when you're drawing mecha." "If you just make it a simple circle, it'll look like a potato." Sometimes he'd even ask me about art materials and how to use them.

At any rate, I wouldn't be who I am today without Mr. Yasuhiko. All I can say is that I'm very fortunate to have had someone like that so close to me.

(1) I think the English loanword コピー here implies "photocopy."

In the previous installment, I shared some reminiscences of Mr. Yoshikazu Yasuhiko. The first episode of Mobile Suit Gundam The Origin, which Mr. Yasuhiko worked on, was released this spring. (1)

As a result, since around the end of last year, the vigorous Mr. Yasuhiko has been showing up frequently in the Internet news and so forth. "Good, good," I thought. Then I received a New Year's card from him in which he wrote something like "I think it's pretty well made, so please check it out ♥ (↑a slight fabrication)." Oh no, I thought, I can't see him until I've watched it... That's what I've been thinking about lately.

In these pages, I'm presenting my own personal experience of Sunrise during the Showa era, so I hope you'll forgive me if along the way I sometimes mention my own private stories as well.

As far as the sponsor and the producer (Tohokushinsha) were concerned, Reideen the Brave was a considerable hit.

This is something I heard directly from Director Nagahama, so I expect there aren't any official records of it, but for a while there was talk of making a followup sequel. It would turn out that the protagonist Akira actually had a twin, and another left-handed machine would appear, controlled by this boy. The plan was that Reideen II would feature a symmetrical pair of Reideens.

However, it seems there were grown-up matters involved, and ultimately Reideen ended as it was in March 1976. That was exactly when I graduated from high school.

When I was a failing student, Mr. Iizuka told me "Be sure to graduate properly!" So on my way home from the graduation ceremony, still wearing the sailor suit I'd only ever worn for field trips and the entrance ceremony, I stopped by the studio with my diploma to say "I graduated properly!" When I did that, Director Nagahama said "Let me buy you something to celebrate." He bought me a music single from 3000 Leagues in Search of Mother from the only record store in Kami-Igusa, which isn't there anymore.

I don't remember anything about my graduation ceremony, but I remember that like it was only yesterday. It makes me realize just how central my visits to Kami-Igusa were to my life back then.

Director Nagahama and the rest of the Reideen production crew moved on to a new program produced by Toei, Super Electromagnetic Robo Com-Battler V. Rather than Studio 1, on the second floor above a coffee shop, their new production site was Studio 2, where the production of Star of La Seine had now ended.

After graduation, I'd intended to go to a nearby fine arts or design school like my manga friends. But due to my family situation, I ended up having to help out with the family business for about three months after graduation, so I could only visit Kami-Igusa about twice a month. As a result, I was left out of the Com-V team. Obviously, I wouldn't provide much fighting strength if I could only show up once every two weeks.

The people who went in to the Com-V studio instead were Ms. Yumiko Tsukamoto, who later became a scriptwriter and light novel writer, and Ms. Mitsuko Kase.

As I've previously mentioned, Ms. Kase started working as an animator at the end of Reideen while she was still attending an animation school, and as of Com-V she became a member of the studio staff.

Ms. Yumiko Tsukamoto was a fan who started coming in towards the end, bringing a notebook full of her carefully written impressions of each episode. She also wanted to try animating. So while she was attending college, animation director Akihiro Kanayama taught her the basics in the Com-V studio, and she began assisting with drawing and finishing.

At the time, I think the only female staff at Sunrise were these two, the people in accounting, and Ms. Sanae Takekawa at Studio 1. Nonetheless, with the addition of these two, the percentage of women had now doubled. (laughs)

The "120% feminine power" of the beautiful Tsukamocchan and Kaseppe. Kawahara rates herself at "-120%."

Meanwhile, after the production site moved to Studio 2, Studio 1 was making ends meet by subcontracting on other companies' works. But they were purely assisting on a limited number of episodes.

I've briefly explained this before, but at the time, Sunrise's only full-time employees were the people responsible for management and accounting. All the staff involved in producing the works on site were contract employees. This was an arrangement in which they received a fixed salary under a contract covering a specific work or a specific period of time. Also, most creators such as scriptwriters, editors, and animators were self-employed freelancers, so some of them were working for multiple companies at the same time, and many would switch between companies with each work. Contract employees could also go to a different company when they reached the end of their contract term.

Thus, many of the freelance creators who weren't part of the Com-V production crew probably took jobs with other companies. As for production staff like the production assistants, if their contracts were renewed, they'd be responsible for the production of works by other companies that Sunrise had taken on.

One thing I knew Studio 1 was subcontracting for at the time was Tatsunoko Production's Gowapper-5 Gordam. The paints used on the cels for this program weren't the "Taiyou Color" ones that Sunrise normally used, but those made by a company called "STAC." If we could use Taiyou Color paint for a given color, we'd do that, but if not we'd have to order it. Still, this was an opportunity to experience the differences between companies, in everything from animation paper to paints, and it helped me to build my own skills.

Anyway, once or twice a month I'd go to visit Mr. Iizuka, or drop by Studio 2 to see Mr. Nagahama. If there was anything I could assist with on that day, I'd help them out. I ended helping out Mr. Iizuka in the planning office more than I was doing actual production work.

And what I was doing most often was answering fan mail. A lot of this fan mail came to the TV stations, but since questions and opinions about content could only be handled by Sunrise, which was doing the production, they were generally forwarded on to us. There were some that came to Sunrise directly, but the production site was too busy to deal with them, and at the time we didn't have any kind of publicity department. So most of them ended up going to Mr. Iizuka.

The exception was when it was addressed to a director or some other specific person. In particular, Director Nagahama was famous for sending very gracious responses to these kinds of fan letters.

I think it was a little after this point in time, but one of the people who sent in mecha designs addressed to Director Nagahama was Mr. Yutaka Izubuchi, who later went from mecha designer to series director. It was Mr. Nagahama who noticed Mr. Izubuchi's talents and led him to his anime debut, designing enemy robots for Fighting General Daimos. Then there were two women who sent him enthusiastic fan mail, and made their scriptwriting debut on Daimos under the director's guidance, using the name "Chizuru Takahama." The aforementioned Ms. Tsukamoto, after Mr. Nagahama had read the impressions she continued to write, also made her pro debut writing Super Electromagnetic Machine Voltes V scripts for him.

Nowadays, to get a job at Sunrise, I gather most people follow a fairly typical "job hunting" route involving entrance tests and interviews. Of course, I'm sure that's not easy. But it means anyone can get access to that window. Back then, there were no jobs like that for new graduates (when there were vacancies, they'd recruit via newspaper advertisements and so forth).

That's mainly because the company wasn't big enough to require that kind of system. And secondly, because of its small scale, it needed people who were "immediately battle-ready." If you have a personnel shortage today, then you need to cover that tomorrow. So if you said "I want to work here because I love anime," you'd be turned away even if you'd graduated top of your class from one of Tokyo's Four Universities. On the other hand, if you had skills the company needed "right now," they'd take you even if you didn't have academic credentials or a lot of anime expertise.

Back then, it was said that some of the production assistants on site were people who didn't know anything about anime, but they'd joined the company because they were good at driving, liked spending all day in the car, and didn't mind staying up all night. (In the analog era, much of a production assistant's job was communicating between outsourced workers via car, at all hours of the day.)

So how could people like me, and the people I mentioned above, slip in as well? It's simply because, among the staff who were working every day on the actual production site, there were some who had the nerve to say "This seems like an interesting person, so let's try training them."

Unlike today, in those days there was no societal recognition of anime fans. Most people had the impression that "anime fan" meant "a weird, childish person with no sense of social etiquette," and I'm sure there were fans like that. As a result, even within Sunrise, there were more than a few people who thought "Anyone who says they love TV manga even though they're old enough to know better is too dangerous to work here."

This perception remained for a long time time afterwards. In my experience, when I was officially assigned to the planning office at the beginning of the 1980s after working on the production sites of several later works, a manager at the time told me "Since you came up from fandom, there's some resistance to promoting you to the planning office, which is at the heart of the company. If anything ever leaks before it goes on the air, you'll be the first one they suspect. So if that happens, you can expect they'll demand your resignation." (Nothing like that ever actually happened.)

Of course that didn't feel good, but that was the nature of the times, and it wasn't something you could dispel based on ability or experience. Perhaps you could say it was an era where you had to prove yourself by working hard enough to overcome it.

The fan mail back then ranged from letters saying "I love so-and-so!" to ones containing razor blades and demanding "Why did you kill so-and-so?!" as well as ones asking things like "Please look at my drawings" and "How can I get a job at your company?" Mr. Iizuka told me, "You understand both the feelings of the fans and our own situation, right? Please answer any fan letters that you think require a response."

At that point, the planning office had moved from the fifth floor where I previously described meeting Mr. Yasuhiko, to an ordinary apartment building nearby. A workspace had been set up with a low table, in a Japanese-style 2DK equipped with a small kitchen. (2)

"My daughter is a big fan of Sharkin, and she says she'll slit her wrists and die if she can't get a cel of him."

You might wonder whether this was just a ruse to get a cel, but the letter was very serious, and earnestly expressed the emotions of a mother who didn't know what to do because she didn't understand her daughter's feelings.

I wrote a reply saying that unfortunately, our cels of Sharkin had already been disposed of, and for the sake of fairness to the fans we couldn't give her special treatment no matter what the reason. Furthermore, if her daughter was seriously saying something as silly and selfish as "I'll kill myself," then she should take her to the hospital. And first of all, I asked her to show this reply to the daughter herself. (Of course, this was an era when all of this was written by hand.)

About a week later, a splendid box of sweets arrived at the planning office. It was accompanied by a letter from the mother saying, "I showed my daughter your letter, and she calmed right down. She kept it and treasured it carefully. Thank you so much." We also received a separate reply from the daughter herself, apologizing for causing so much trouble for her mother and for Sunrise with her thoughtless words, and saying that she'd always be rooting for us from now on. I was honestly very relieved. A young woman's life might have depended on my response.

And I realized once again how great Mr. Iizuka was. I was fresh out of high school, and hadn't yet lost my fan sensibilities. In doing this job, I was learning how to properly differentiate between the fan and business viewpoints.

I should also note that Mr. Iizuka gave me the box of sweets we received on this occasion, saying "You should have this, Hiroppe."

(1) The first episode of Gundam The Origin was previewed in theaters starting February 28, 2015, and then released on video on April 24. This issue of Great Mechanics G was published on March 18 of that year, technically the first day of spring, but the Japanese text phrases this in the past tense.

(2) The term 和室 (washitsu), translated here as "Japanese-style," refers to traditional Japanese rooms with tatami mats on the floors and sliding doors. "2DK" means the apartment has two general-purpose rooms in addition to the dining and kitchen areas.

In April 1976, a new program began airing, for whose actual production Sunrise Studio Ltd. was responsible. The name of this program was Super Electromagnetic Robo Com-Battler V. It was a really gorgeous work in which five piloted combat mecha combined to form a robot, and you could play with the toys in almost the same way.

The scriptwriting, episode direction, and animation were handled mainly by staff who were continuing on from Reideen the Brave. In other words, Sunrise had committed most of the main staff it had at the time, and it was naturally a major job for the company itself. However, the producing company (copyright holder) was the Toei Company. (1)

Soeisha Inc., the parent company of the Sunrise Studio where 0-Tester and Reideen were made, was still a subsidiary of Tohokushinsha. Thus the family-oriented robot comedy Robokko Beeton, produced by Tohokushinsha (and the Tokyu Agency), began airing in October of the same year. After the Com-Battler crew relocated to Studio 2, which had previously been used for the production of Star of La Seine, Studio 1 was placed in charge of this new program.

The series director, Mr. Masaaki Osumi, was also famous for directing the first Lupin III. This was the first time I'd personally met him, but he'd also worked on Star of La Seine. The episode directors included Mr. Takao Yotsuji, who I've discussed previously, as well as Mr. Satoshi Dezaki, Mr. Masuji Harata, and Mr. Yoshiyuki Tomino.

You'll already know about Mr. Tomino. Satoshi Dezaki, the older brother of Mr. Osamu Dezaki of Tomorrow's Joe and Treasure Island fame, came from Mushi Production and had previously worked on Reideen and La Seine. He was a calm and dapper person. Mr. Masuji Harata was a member of Akabanten, a group that also included Director Ryosuke Takahashi of Armored Trooper Votoms, and he was a unique character who loved jokes.

The character designer, Mr. Yoshikazu Yasuhiko, was also working on Com-Battler but that's what makes him a genius. He actually participated in the planning of this work, and in addition to the guest characters for each episode, he sometimes handled the scripting and direction as well. He also did animation direction under the credit "Yasuhiko Tadano." (2)

In a sense, Robokko Beeton was the polar opposite of the straightforward giant robot show Com-Battler. Though it was supposed to be family-oriented, it certainly wasn't a well-mannered work. In particular, the rival of the grade-schooler hero was a wild "bratty old man" with a little mustache, who was immensely wealthy but remained mentally childish. (3) As it continued, it went in a somewhat slapstick direction, and with things like the appearance of a sexy girl robot in the second half, I think it became a hidden masterpiece whose sensibilities were beyond anything people expected at the time. Thinking back on it now, this wildness was probably due to the presence of so many Mushi Production alumni around Sunrise.

Particularly noteworthy for the readers is the fact that Beeton was actually the first Sunrise work with which Mr. Kunio Okawara was involved. It was Mr. Okawara who did the internal diagrams of the robot Beeton, the hero's partner who served as a second protagonist. These were meant for publication in things like the children's magazines that were running the Beeton manga, so perhaps some veteran readers may have seen them when they were children.

As I briefly mentioned last time, I'd been left out of the Com-Battler team, so I ended up joining the Beeton team to do odd jobs, principally retake processing. "Retake processing" basically means "fixing mistakes." As many of you probably know, there are many steps in the anime production process, and for some reason correcting a mistake has always been called a "retake." Of course, errors can be corrected at any number of places, and normally they're sent back to the department responsible to be fixed.

However, the retake processing I'm talking about here addressed problems that weren't noticed until the stage where we were checking film that had already been shot. When minor adjustments came up at the production site, like partial mistakes in coloring, something wasn't drawn that should have been, or for some reason the episode director wanted something changed or a process applied, we'd save the time and labor of sending things back one by one and deal with it on site at the production studio.

Thus, the nature of the work varied a lot. Sometimes we were painting cels, sometimes we were drawing. When necessary, we'd be applying effects (special effects using an airbrush or a sponge) or hand-tracing with a pen. In any case, these events arose when the schedule was proceeding on the assumption that the time for corrections had already passed, and they had to be resolved as quickly as possible so that things could go back to the original production line. For that reason, we'd sometimes employ "cheats" that wouldn't be used in the regular work process.

Let me introduce a few of these.

[ Cut and paste ]...Cutting out part of a drawing from one cel, and sticking it onto a different cel by affixing double-sided tape to the back. This is done mainly when the size of the cel changes, in order to save the labor of retracing and repainting it. The trick is that the thick part where it was cut is painted black with a felt-tip marker, to make it harder to notice the shadow created by the thickness of the pasted portion.

[ Overpainting ]...When there's a partial coloring mistake, a cel that was originally painted from the back can have the correct colors applied from the front. Since cel paint is handled differently from ordinary paint, it takes some skill to apply it thinly and evenly without overlapping the traced lines.

[ Covering ]...As with overpainting, when part of a cel has coloring errors or you want to hide unnecessary lines, you can cover it with another traced and painted cel. However, because this covers the entire cel with an extra layer, rather than just the covered area, the image will inevitably be darkened. Thus it's unsuitable for bright scenes, and its use depends on the context.

These are all methods for correcting hand drawings, so these skills are no longer necessary in the digital era. However, you can't choose the appropriate processing method unless you understand all the techniques of cel animation. Because I was responsible for this work, I was able to learn most of the skills needed for making TV animation even though I didn't make a particular study of it.

For the sake of work efficiency, my workbench was next to the "pre-shooting desk" (where the episode directors checked the materials required for each cut before sending them to photography) made up of combined long tables. As well as pre-shooting, this was also used for the work of "cutting," where the episode directors and film editors adjusted the photographed film. So I was always able to watch the episode directors at work, and talk to them directly about various things.

In other words, since I could understand both the content of the work and the production flow, I could reflect their intentions directly in my retakes. I was also able to get a complete picture of anime creation. And above all, since I had a good view of the workflow carried out through division of labor, I learned from firsthand experience what kinds of problems came up before and after each task. This would prove to be a very useful benefit in my subsequent animation work.

The atmosphere around the studio was always freewheeling. But the naughtiest among the Beeton staff (though don't get me wrong, he was never particularly violent) was surely Mr. Takao Yotsuji.

As I've previously noted, Mr. Yotsuji really likes rock-and-roll. His working style is also that of a rock-and-roller who thinks it's boring to be like an ordinary person. In everything he does, he likes to do things differently from other people. That's why he was so good at depicting the crazy behavior of the aforementioned Gakioyaji. In a sense, I think the character's irrational slapstick antics may have embodied Mr. Yotsuji's own ideals (?).

The staff would often stock up on groceries in anticipation of having to stay up all night. At the time, Mr. Yotsuji was really into wine, and during pre-shooting he'd come in with two or three bottles of wine and a baguette. You might think that sounds really classy, but you'd be very much mistaken. In the middle of the day, he'd start pouring this wine into a mug and gulping it down as he was doing the pre-shooting.

To prevent cels from sticking together, sheets of tissue paper, thin enough to see through, are placed between them. However, these get in the way during pre-shooting, and the episode directors often peel them off and discard them. That's why there's a large cardboard trash bin under the pre-shooting desk.

Perhaps it was partly the wine, but Mr. Yotsuji would peel off the flimsy tissue paper sheets one after another and scatter them all over the floor, ignoring the huge trash bin at his feet, humming as he did so. At first I'd just grumble and pick them up from time to time, putting them in the trash bin. But eventually my patience ran out. "Hey," I yelled, "who do you think is gonna clean these up?! Can't you put 'em in the bin properly?!" Mr. Yotsuji suddenly straightened up, apologizing and sweating profusely. For some reason, after that he never defied me again. (laughs)

Jumping ahead to 1997, almost 25 years after Beeton, I was in Vancouver, Canada, doing live-action filming for a certain work (this is getting long, so I'll save that story for another day). (4) Then it was suggested that we shoot a "making-of" feature about the filming.

And so Mr. Yotsuji received an unexpected phone call from Canada. This was in December, after Christmas, and the year was drawing to an end. In addition to anime, Mr. Yotsuji also directs things like live-action reportage programs, and when I contacted him just to give it a try, he agreed without a moment's hesitation. To my amazement, he showed up by himself in Vancouver two days later.

We stayed in the same hotel for about a month. He arranged for a cameraman and an interpreter on the set, then came to the filming locations and singlehandedly took care of shooting the making-of material. Meanwhile, on days when we weren't filming, the two of us would visit museums and explore Chinatown, go together to eat ethnic foods we loved such as Thai and Indian, and spend our time being pretty much inseparable. That was a lot of fun.

What matters in life is being curious and enjoying yourself. If you can't entertain yourself, you can't entertain others... He's never said this in words, but I think that's the kind of director Takao Yotsuji is. I think you could say that the "J9 series" he later directed was born from this Yotsuji-ism.

Anyway, I'd say the Beeton team was generally peaceful. But I remember one "disaster" for which I still feel some personal responsibility.

For each episode, Mr. Yasuhiko would do an original drawing of Beeton that matched the episode contents. This was inserted as a title background, and it was my job to trace and color it. In one of the summer episodes the drawing showed Beeton holding a watermelon. I don't know what I was thinking, but instead of painting the melon green with black stripes, I painted it green with white stripes. And for some reason, nobody noticed it. Some people did think there was something weird about it, but it wasn't until it aired that we realized it was because of the white stripes.

If this had been a work that was really popular with the fans, I'm sure the TV station and the studio would have gotten letters of complaint. In my career in anime, this a terrible disgrace that I'll never forget. (wry laughter)

(1) In the Japanese text, Kawahara specifies this is 東映(本社)—literally "Toei (head office)"—perhaps to distinguish it from the animation studio Toei Doga.

(2) In Japanese name order, "Tadano Yasuhiko" means "It's just Yasuhiko."

(3) "Bratty old man" is a literal translation of the character's name, ガキオヤジ (Gakioyaji).

(4) This work would be the infamous G-Saviour.

Even now, a five-story blue building still stands diagonally across from Kami-Igusa Station. This is the Koyo Building, a building owned by a real-estate company which seems to have somehow been linked by fate to the "Sunrise" name. In 1975, the Star of La Seine production studio was established on its fourth floor. Up until 1978, this location was known as Studio 2. Its floor space was about half to two-thirds that of Studio 1. The fifth floor was even more cramped, and from this time it became the "head office" where the president and the accounting staff had their desks.

This Studio 2 inherited the main staff from Reideen the Brave, who did the actual production work on the Toei-produced Super Electromagnetic Robo Com-Battler V, as well as the following Super Electromagnetic Machine Voltes V and Fighting General Daimos. But while I say "main staff," in fact many of its members were carried over from the La Seine crew, and in terms of the production site it might be more accurate to call it a mixed team from Reideen and La Seine.

The producer (copyright holder) of Com-V was the Toei Company, and its broadcast day and time were different from Reideen. Nonetheless, many anime fans recognized it as "the successor to Reideen." At the time, there really were't any information sources for anime like there are today, and the main sponsor was still the "Chogokin" toymaker Popy. Many of the staff titles displayed on the screen were the same as Reideen, and even on the production side, although the studio itself was now Studio 2, the post-recording and dubbing work was still being done at Tohokushinsha, and the staff roster at the studio was also similar. The outsourced animators and finishers were more or less the same, and since the work environment hadn't really changed, the completed film maintained the same atmosphere.

For better or worse, in those days the people working at the production site didn't feel any "external pressure" that would make them conscious of who held the copyrights. To the managers, it probably made a big difference who the rights-holder was, but honestly it was an era where that ultimately didn't matter to the viewers or the production site.

And I think, above all, there was the fact that Director Tadao Nagahama, who had ultimately guided Reideen to become a success, was working on it. The personality of the series director becomes the personality not only of the work, but of the studio itself. As far as I know, that was always the case with Showa-era Sunrise. From the second half of Reideen, to the three Toei-owned works that followed it (or at least half of the final one), you could probably describe them as being "works by the Nagahama studio."

This chain of events later led to the creation of works targeted at the late teens, such as Mobile Suit Gundam and Armored Trooper Votoms. So the truth is, one reason we now have the consensus that "anime is part of Japanese culture" was the existence of Director Nagahama. I hope the readers will be sure to remember this.

Director Nagahama was a native son of Kyushu, born in 1932. From a puppet theater company, he went on to direct the old Tokyo Movie series New Obake no Q-Tarō and Samurai Giants, followed by the smash hit Star of the Giants. When I first met him in 1975, he was 43 years old, a charming little "uncle" with a goatee beard.

I've already talked about how much he cared for his fans, but he had a bold personality and there are some anecdotes I'd hesitate to share here. I won't go into the details (laughs), but for example, he enjoyed recounting how when he was younger, was he driving in a car with some friends and they came across a police officer. Through unspoken teamwork, they used their acting skills to completely baffle him. (This isn't something children should imitate.) Meanwhile, although he couldn't drink alcohol, I hear he'd keep everyone company at drinking parties by drinking "milk" all night long.

Mr. Nagahama listened keenly to people like me, who cried "Rei-sama is so cool~" even though we were old enough to know better. He was delighted that there were people like us in the audience, and threw his complete support behind our fan activities.

This didn't just mean showing us around the dubbing studio or giving us cels as presents. By giving us a brief lecture on the so-called "ownership of rights in adult society" that naive children knew nothing about, and putting in a good word with the appropriate people, he secured tacit permission for our fan activities. (1)

In hindsight, this was really extraordinary. Perhaps it's because everything was still in a "lenient era," but I can say with certainty that he must have persuaded the rights-holders at the time by saying something like "These kids really love Reideen. The girls are buying children's goods and toys they don't even play with. If we take care of these fans, the business will eventually benefit."

It was thanks to him that the "RFC" (Reideen Fan Club) I was involved in was able to borrow the TV broadcast film for several episodes from Tohokushinsha (for a fee, or course), and hold several screenings attended by more than a thousand people. Though the event organizers were mostly ordinary female college and high-school students, we had to follow permitting procedures such as the Fire Service Act to hold events in thousand-person venues. He taught us about the necessity of following all these procedures. The fan side also had to put effort into these events, too, obtaining 16mm projectionist licenses and driver's licenses to transport equipment.

On the day itself, several voice actors, scriptwriters, animators, and other production staff showed up. Back then, it was rare for these kinds of "insiders" to make guest appearances at fan-run events, but even Tohokushinsha executives came to the venue. For officials of the copyright holder to accept our invitation could be considered a kind of implicit official approval. (However, we were under strict orders not to make a profit.)

Director Nagahama, anticipating the popularization of home video, was also running a business that did video recordings of things like weddings. So at the venue, he summoned his staff to do a documentary recording. This was the era of "K-60 Betamax," but I still have a copy of one of those tapes in my hands.

With this support from Mr. Nagahama, the anime fans of the time learned just how much they could do if they tried. And, perhaps inspired by this activity, some people also began to feel they could create media targeted at teenagers. This trend was surely one of the factors that eventually led to the establishment of specialized magazines devoted to anime programs.

What's more, it seems this experience had a big impact on Director Tomino, who was if anything rather negative about fan activities back then. It was actually me who dragged the reluctant Director Tomino along to the second screening event and made him go up on stage. (Lately, Director Tomino seems to be misremembering this as a Triton of the Sea event, but it was a Reideen event.) (laughs) Perhaps for this reason, Director Tomino later said "In a way, you were my teacher, Kazama-kun." Of course, maybe he was being sarcastic. (wry laughter)

Anyway, back to the story. I was talking about the second screening event. Unfortunately, that was the same day Voltes was airing in the Kanto region. (2) But Director Nagahama wanted everyone gathered there to see it, so somehow he arranged to have an extra copy of the film that was going to be broadcast that day developed at his own expense, and he did us the ultra-generous service of screening it at the venue at the same time it went on the air. This was before home video had become commonplace... I've never heard, before or since, of an anime director doing such a thing for the fans.

From another point of view, this also showed how much effort Director Nagahama was putting into Voltes.

Director Nagahama was from an older generation than Director Tomino, Director Ryosuke Takahashi, and so forth. When they were children, his generation experienced defeat in war, and from their adolescence to early adulthood Japan was shaken by the Anpo protests. Everything that up until yesterday was "white" suddenly became "black," and this experience gave his generation a strong underlying spirit of institutional criticism. With Reideen and Com-V, Director Nagahama felt that anime had the power to appeal to a generation that was open to reason, and this idealism was also reflected in his work Voltes V.

None of this was unique to Director Nagahama, and the spirit of institutional criticism was the backbone of many Showa anime works. Perhaps that's why so many of them have rich worldviews and a sense of grounded, realistic weightiness. But Director Nagahama was probably the only one who expressed it so straightforwardly. This approach was consistent in Daimos and Future Robot Daltanious as well, and continued on to Rose of Versailles which he did after leaving Sunrise.

However, works with this kind of "ideological" color require a delicate balance. When I sensed this ideological flavor in the latter half of Voltes, I wasn't yet mature enough to readily accept it. Little by little, I began to distance myself from Director Nagahama. Around the same time, I was getting busier on the production sites of the works I was responsible for, so I could no longer really participate in fan activities.

Perhaps Director Nagahama also sensed this distancing. Just before the broadcast of Daltanious began, I ran into Director Nagahama in the office for the first time in a while, and he said something to me that I've never forgotten.

"This time, I think you'll like it too, Kazama-kun."

And that was the last time we ever spoke.

After his sudden passing, I well remember the clear blue sky on the day of his funeral. I thought that sky perfectly suited his openhearted personality. But even now, 35 years after his death, I can't help regretting that I couldn't tell Director Nagahama, who had cared so deeply for me, how much I enjoyed Daltanious.

This was some time after Robokko Beeton entered its second half. I don't recall exactly when this was, but it was probably in the spring, since the weather was neither hot nor cold. (3)

"Sorry about this, Hiroppe, but could you clean up Studio 3?"

Mr. Iizuka, who would later become my official boss, was then singlehandedly running the planning desk, materials management, and publicity. He'd led me up the narrow stairs of a building right in front of the train station, which housed a grocery called "Yaoshou." This was Studio 3, then known as the "Kum Studio," which had produced Kum Kum and the later Dinosaurs Catcher Born Free. (4)

It was even more cramped than Studio 1, on the second floor above a coffee shop. It was a space with a sink and a one-room closet, and bumpy vinyl floor tiles. But what surprised me the most was that, cramped as it was, there were cut bags piled up all over the floor about as high as my waist.

"We're going to be using this place soon, so could you tidy up these cels? Beeton should be fine for the time being, so I'd like you to organize the cels in the meantime."

I honestly felt faint just looking at this vast amount of material...

For roughly the next two weeks, I spent my days wrestling with about 78 episodes' worth of cels (249,600 by my rough estimate, hah) from Kum Kum and Born Free. I had no idea this would later become my own workplace. The cramped first-generation Studio 3, with its bumpy floor, was to become the production site for Super Machine Zambot 3, Sunrise's first original program.

(1) I think the Japanese phrase 「大人社会の権利関係」, translated here as "the ownership of rights in adult society," probably refers to intellectual property rights such as trademarks and copyrights.

(2) This event took place on January 7, 1978, simultaneously with the broadcast of Voltes V episode 32.

(3) The 50-episode series Robokko Beeton reached its halfway point at the beginning of April 1977, six months before the broadcast debut of Zambot 3.

(4) The broadcast of Born Free ended in March 1977, around the halfway point of Robokko Beeton.

"Even though it was our first original work, it had the weakest production system, just the worst." That's how one former Super Machine Zambot 3 staffer would complain in later years. It's harsh, but it's true.